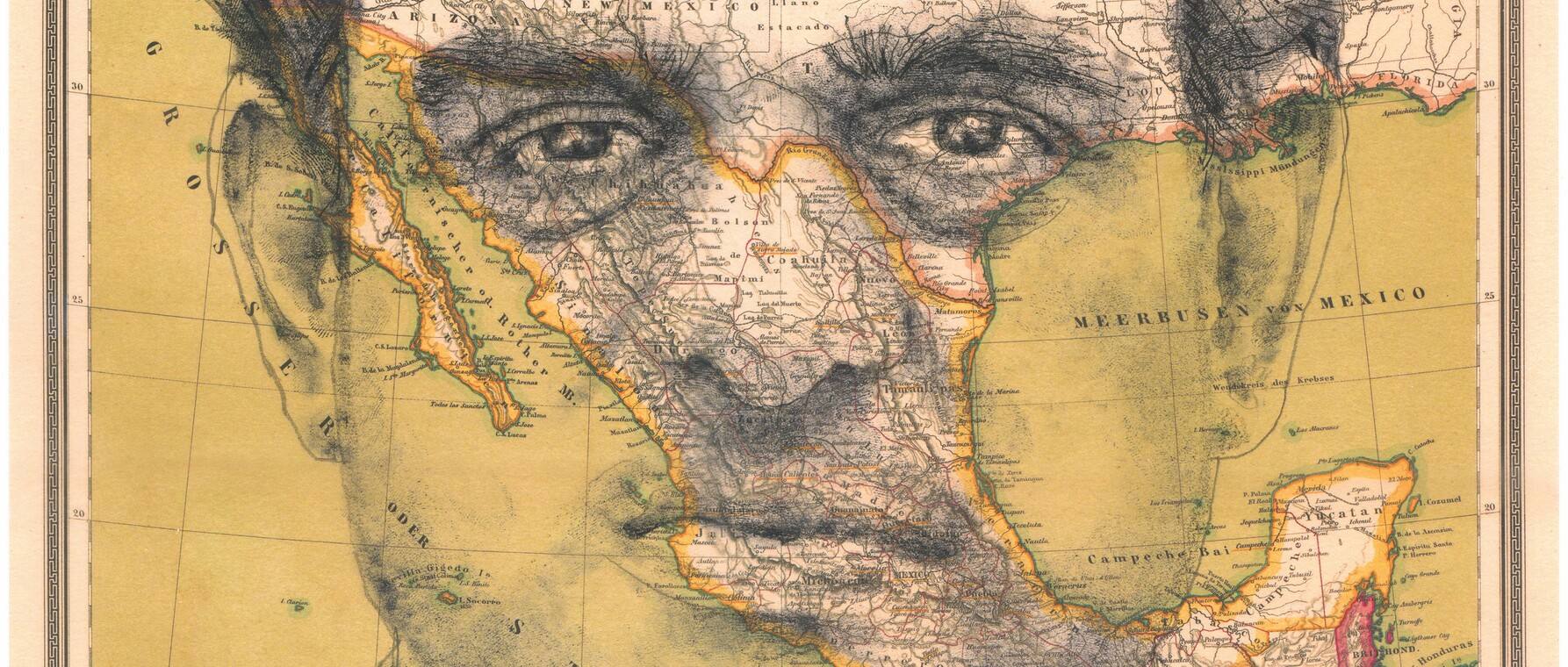

Imagined Past

Emilio Kourí, AB '84, PhD '96, studies the social and economic history of rural Mexico since Independence.

Emilio Kourí, AB ’84, PhD ’96, studies the social and economic history of rural Mexico since Independence. He is particularly interested in the idea of the "Indian Pueblo" created by the Spanish based on pre-Hispanic indigenous communities. The mythology of these communities continues to resonate in Mexico today.

Would you say that the history of Mexico is a history of farming and land ownership?

For thousands of years, the life of people in the Mexican region—particularly in the center and the south—has been bound to agriculture. It is the birthplace of corn cultivation, and a series of cultures that arose and continue today were built around the consumption and cultivation of corn. Prior to the Spanish conquest, village life and agricultural life were the center of everyone’s existence. Even after Independence in the 19th century, Mexico remained centered on agriculture. I’m interested in that agrarian path because it’s really at the core of the lived experience, back to the origins of agriculture—maybe 5,000 years before the common era until a short while ago.

It sounds as though the area was fertile and profitable. What happened after the Spanish arrived?

The identity of Mexico is largely tied to the story of indigenous people living in villages that governed themselves. The arrival of and conquest by the Spaniards changed everything dramatically, but it did not change the centrality of agriculture. A huge percentage of the native population—some say up to 90 percent—died from epidemics, violence, war, and disruptions, but most of those who remained continued to live in the countryside. What did change was that the Spaniards reorganized land tenure. From the existing pre-Hispanic communities, the Spanish created pueblos that were endowed with lands by the King of Spain.

These imagined communities were reinvented. . . without a political component.

–Emilio Kourí, AB ’84, PhD ’96

Much of the political and social history since the Spanish conquest and into the 19th century is really about the fate of those communities: the lands, the political rights, the efforts to fend off interlopers from the neighboring states that the Spaniards controlled. This is a core part of the history, but it’s also a core part of that idea of the past—that this was a place of natives and later mixed communities who held the land that way.

How long did these communities last?

That structure stood in place until the second half of the 19th century, when modern ideas of social progress and the idea of the individual farmer took hold in Mexico. Politicians abolished collective or communal property because they thought that it was a drawback to economic and social progress. In part, the disruption, the dispossession, and the disaffection produced by that major transformation in the historical status of communal property led to the agrarian outbreaks around the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Certainly, some of the groups that rose to fight during the revolution wanted the restoration of the communal status of village lands. After the revolution, profound agrarian reform in the 20th century created new communities imagined to be like the old ones, but, in fact, they were quite different.

Does your research address this difference?

My work is, in part, about how that reform was predicated on certain ideas about the past: about the nature of those communities, what held them together, and how they worked. I argue that some of the difficulties that 20th-century land reform faced have to do with the implementation of policies that were based on an understanding of the past that was, in some ways, defective. Communal property is connected to romantic social qualities: egalitarianism, reciprocity, and solidarity working harmoniously until, in the second half of the 19th century, politicians pushed them to dissolve as a path to progress and modernity. In fact, it was a much more complicated story. As land holding units, they were from the start very unequal, very stratified. Their real virtue lies in the way they became the foundation for local political power and organization. When these “imagined communities” were reinvented by the government, they were reinvented without a political component. And I say imagined communities because, although they did exist as communal land holding communities, the meaning of communalism in pre-Hispanic times was often not the same as the romanticized version.

How has that lack of political engagement affected Mexico?

Land reform was a huge political achievement. By the late 1930s, it had led to the destruction and dissolution of the old estates that had arisen after the Spanish conquest in the 16th and 17th centuries, and those lands were distributed into a newly created communal land holding association of the sort that I mentioned. That is, historically, without question, quite significant. The issue is why they didn’t lead, in the countryside, to the kind of prosperity and progress that people once hoped they would. The absence of the political element left them unable to establish or fight for what they needed and, through a kind of growing clientelism, they essentially became wards of the state when it came to political rights and representation. Mexico had a single party in power from the 1940s until the year 2000, and the political foundation of that stability came largely from these captive communities that had no other political form of redress.

Did that absence of political power and development of a single party have negative impact on the country as a whole?

Agricultural reform was one example of a neglect that has had long-term consequences. Municipal or city power was stripped out of politics in the land communities and elsewhere, and that weakened the fabric of local society. The revolution initially promised to reverse that but, in fact, did not and continued the process of weakening local power. And many of Mexico’s problems—not just the ones related to agriculture—in localities that feed the violence of drug dealing and so on are connected to the sense of abandonment of space at the local level. Sooner or later, that is going to have to be restored.

Illustration by Daniel Baxter

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast