Talkin’ ’Bout Regeneration

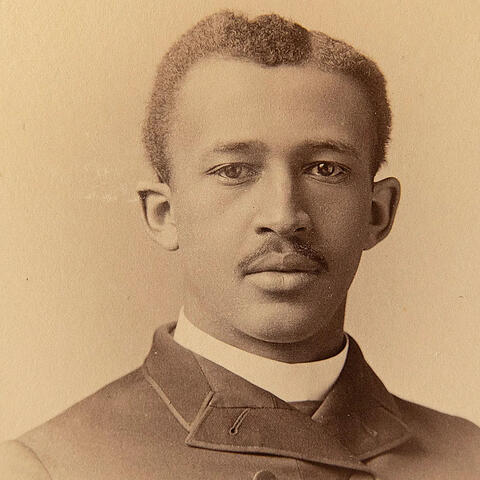

Nadia Rosenthal, PhD ’81

Nadia Rosenthal is the scientific director and a professor at the Jackson Laboratory for Mammalian Genetics in Bar Harbor, Maine, where she researches how genetics play a role in development and regeneration. Rosenthal discusses her journey through Harvard as a female scientist, a midnight “eureka” moment, and mentoring women who come through her lab.

Cracking the Code

My academic journey started at Harvard. I was an undergraduate at Radcliffe College and I was heavily involved in biology and biomedical sciences. I really wanted to be a scientist, and it was clear to me that graduate school was the way to go. Harvard was a different place at that time, especially for female scientists, but I had a lot of faith in some of the professors and I knew Harvard was involved in lots of active and exciting areas of research. It was a rough six years in graduate school, a real trial by fire, but I stuck around in science because I believed that unless enough women made it into the life sciences then, we'd never bring enough women into the field in the future.

At the time, studying developmental biology like I did was going out of fashion, because molecular biology was becoming more prominent and everyone was focused on cloning. So, I went into molecular biology and did a decade’s worth of work in that field. I decided I really wanted to go back to developmental biology, especially because of its medical relevance and the concepts of organisms repairing themselves after injury.

Mammals are very bad at regeneration, but there are many vertebrates who can repair and regenerate organs and limbs. They do this by using the same genetic codes that developed their organs and limbs when they were embryos. We retain these codes, but we can’t use them the same way they do. One of the big questions in my lab is: if we can figure out the developmental code that directs regeneration, how can we make it clinically relevant? For example, the adult human heart is not regenerative but is there a way to make the damage from a heart attack less of a disaster? We are currently trying to treat heart attacks in mice with certain compounds and approaches, so we can figure out how to replicate embryonic regeneration and healing in them, and ultimately in us.

Late Night Discovery

When I was a graduate student at Harvard, we were in a race to clone and sequence the genome for insulin. The entire scientific community was fighting to do it first, and this was back in the 1970s, when there wasn’t any other way to pass information around other than letters or faxing. I spent a lot of time on that insulin sequencing project.

One night, I was reading along the sequence, trying to figure out if the DNA looked like the RNA it encoded. I noticed that they didn’t match anymore. It was as if you were reading a book, where “the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” read “the quick brown fox . . .” and then for 100 pages it didn't say anything like what you were expecting before finally going to “jumps over the lazy dog” at the end. I had stumbled upon a weird sequence deleted in the RNA that would later be called an intron. No one had ever seen it before, no one knew it existed in the insulin gene until I found it.

That is what keeps me going in science. I tell this story to graduate students all the time, because if you don’t take risks, you don’t take chances, you don’t stay up until 3:00 a.m., you’ll never have that moment of total coolness when you realize you’re the only person in the world who knows this piece of the puzzle.

Getting Women Scientists “Ready to Rock”

I am very passionate about making sure I can mentor women in science. I have had over 75 people come through my lab, not counting undergraduate and high school students, half of them women. Almost all of these have stayed in science or related topics. I follow their careers and it is a joy to see them flourish.

In general, I have found that while men are “ready to rock” when they arrive in the lab, women are still wondering if they’re allowed in the door. That self-doubt has to be dealt with. It helps that I’m a woman because it makes it obvious to them that there is no reason they shouldn’t be walking through that door. It is so much fun to watch women who might start a little wobbly in the lab, and then they get their feet under them, and you can’t stop them from doing what they want to do.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast