Hope for Democracy

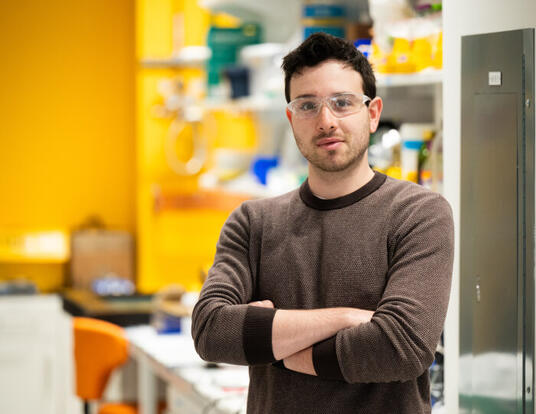

Stephen Ansolabehere says voting is alive and well in the US. That doesn't mean it can't be improved.

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

When a Boston precinct was having trouble with voting, they called Steve Ansolabehere, PhD ’89, Harvard’s Frank G. Thompson Professor of Government and the director of the University’s Center for American Political Studies. The problem at the South Boston school where citizens cast their ballots was long lines. If that sounds trivial, consider that waiting in line, along with inconvenient voting hours and polling locations, may have discouraged an estimated 730,000 people from voting in 2012, according to a white paper that Ansolabehere and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Charles Stewart III submitted to the US Election Assistance Commission in 2013. The opportunity cost of lost wages was an estimated $544 million.

Ansolabehere called Stewart and his MIT colleague Stephen Graves, an expert in operations management. The trio arrived at the school, looked around, and sized up the problem.

“Two precincts were voting in one location,” Ansolabehere remembers. “One precinct was large; the other was small. The first table you encountered when you entered was for the small precinct, so the line was out the door with people who needed to vote at the large one. Precinct signs were taped low to the tables so most people couldn’t see them. We suggested they put the large precinct at the first table and post the signs up high. The problem went away.”

Steve Ansolabehere would be the first to admit that the solutions to many of the challenges facing US democracy are not as simple as the ones he encountered on that day in South Boston. The notion that the 2020 election was “stolen” has become an article of faith for politicians on the right. On the left, there are concerns about voter suppression, particularly in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision to strike down a portion of the landmark Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965. But Ansolabehere says US elections are both more secure and fairer than their most strident critics contend. Moreover, just as with the polling station he and his MIT colleagues visited, some relatively straightforward, practical changes could translate into big improvements both in access and election integrity.

The Truth about Voter Fraud

Nearly two-thirds of Americans are confident in the accuracy of US elections, according to a 2022 Gallup poll, but concerns vary dramatically by political affiliation. Around 85 percent of Democrats are very or somewhat confident in election integrity compared to only 40 percent of Republicans—the largest gap Gallup has recorded in 20 years.

Ansolabehere says that in-person voter fraud is rare in the US. How rare? Justin Levitt, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, studied more than 1 billion ballots cast in general, primary, special, and municipal elections from 2000 through 2014. He found just 31 instances of fraud. In fact, officials in the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency issued a statement during the waning days of the Trump administration calling the 2020 presidential election “the most secure in American history.”

You’ve got thousands of people scrutinizing [voting] data across the United States. There are election lawyers on both sides looking for evidence of something irregular. If a concern holds water, it usually gets flagged.”

—Steve Ansolabehere

What about allegations of 2016 and 2020 ballots cast in the name of deceased citizens? Ansolabehere cites research that matched voting and death records. “Cases of somebody who had a ballot recorded who had died were extremely rare,” he says. “Even then, some were people who legally voted absentee at their nursing home or elsewhere before the deadline and then they died, which is obviously legal.”

How about accusations of underage voting? Ansolabehere points out that some states and towns allow people as young as 16 to vote in municipal elections. “You’ll see 17-year-olds on the voter files in some places, but they’re not voting in federal or statewide elections,” he says.

A Changing Landscape

The rarity of voter fraud hasn’t stopped legislatures nationwide from passing laws designed to limit access to the ballot box. According to the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice, lawmakers passed at least 17 restrictive measures in 14 states during 2023. The laws include new restrictions on mail-in voting, bans on ballot drop boxes, and stricter photo ID requirements. Ansolabehere acknowledges that more restrictive voting laws impact voter turnout, but the hit is often less than opponents fear.

“It’s been widely studied and debated in the literature and it’s hard to identify a sizable effect of, say, restrictive voter ID laws,” he says. “In Texas, for instance, maybe 25,000 people would be affected one way or the other but that’s a really small percentage in a state with around 16 million voters.”

That said, the legal system has a responsibility to ensure that no one who is eligible is prevented from voting. “The questions for judges looking at new restrictions on voting are, ‘Was there any reason to be concerned about fraud in the first place? Has anyone ever committed fraud with this system? Have these laws ever prevented it?’” Ansolabehere says. “In the court cases where these measures have been thrown out, it’s usually because there’s no evidence that they would improve election integrity but plenty of indication that they would adversely affect certain groups of voters.”

Those “certain groups” are often people of color, particularly since the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder. In that case, the Court struck down section 5 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which required states with a history of racial discrimination to get clearance from the US Department of Justice (DOJ) or a federal court before changing voting laws. In response, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense Fund said Shelby County v. Holder “broke democracy,” “gutted essential protections of the VRA,” “ushered in a wave of discriminatory voting and redistricting laws,” and “irrevocably changed the landscape of voting rights in the United States.”

Ansolabehere says the Court’s decision has had unforeseen consequences—including some that have actually bolstered efforts to secure voting rights. In reality, the DOJ almost always granted section 5 preclearance to states. Once a state got preclearance, it became much more difficult for plaintiffs to sue under section 2 of the VRA, which targets intentional discrimination. Without the prophylactic effect of preclearance, though, the legal landscape changed.

“There were a bunch of new lawsuits in 2015,” Ansolabehere says. “The plaintiffs started winning. Things that were precleared were suddenly thrown out.”

Ansolabehere speaks from personal experience. In 2016, he joined a lawsuit filed by colleague and election lawyer Kevin J. Hamilton alleging racial gerrymandering in North Carolina’s 12th Congressional District. “The legislature packed Black voters into these two districts,” Hamilton explains. “The result of that was to ‘bleach’ the surrounding districts, making them much more white and much friendlier to the party in power. Concentrating Black voters into Black districts and white voters into white ones also tended to eliminate swing districts—places where elections could have been competitive.”

Hamilton says Ansolabehere provided critical research on historical voting patterns and demographics that enabled the plaintiffs to prove lawmakers had divided voters based on the color of their skin. His Harvard colleague was pretty sharp on the witness stand, too.

“Steve testified that the district was the ‘least compact in American history,’” Hamilton remembers. “‘How do you know that?’ asked North Carolina’s attorney Tom Farr during his cross-examination. Steve’s eyes lit up. ‘Oh, that’s easy,’ he said. ‘I just calculated the compactness score of every congressional district in American history and then sorted them.’ Farr was completely shut down.”

Hamilton won the case. A district that had been upheld before Shelby County v. Holder—”one of the worst examples of a racial gerrymander in thirty years,” according to Ansolabehere—was ruled unconstitutional and thrown out. North Carolina created a compact majority Black district in the Charlotte area.

Moreover, Ansolabehere says minority voting has held steady since the Shelby County decision. When it declined, the dip was more likely due to who was on the ballot. “You could see a pretty big spike in Black voting when President Obama was on the ticket and then it dropped when he wasn’t,” he says. “Hispanic voting has continued to trend upward. So it doesn’t look like the end of section 5 has had a big impact on minority turnout—in part because challenges to racial gerrymandering and restrictive laws have been more successful in court.”

Registration and Reform

Although Ansolabehere argues the United States electoral system may be both more secure and accessible than its critics contend, he is conscious of its weaknesses. Among them is the system’s decentralization. “There are 8,000 election offices and about 200,000 precincts throughout the US,” he notes, an often-disconnected network responsible for serving a diverse electorate. The intricate system allows for localized representation but also presents administrative challenges. “In any given election, voters cast ballots for many different offices at once,” Ansolabehere explains. “All those election offices have to generate unique ballots for each precinct, manage the recruitment and training of poll workers, and ensure the accurate tallying and reporting of votes.” Absentee voting adds another layer of complexity to the system.

Stewart says decentralization and the barriers to registration it creates are reasons why the US lags behind other developed nations in the participation rates of voters under the age of 35. “Americans in general—and young people in particular—are notoriously mobile,” he says. “Right now, the system requires people to update their registration whenever they move. Often, people don’t know that.”

To address these issues, Ansolabehere and Stewart suggest several reforms aimed at enhancing participation and accessibility while maintaining election integrity. First is the widespread adoption of automatic voter registration.

“One of the only ways to move the needle on participation rates among young people is to lower the barriers,” Stewart explains. “Automatic registration would allow them to sign up to vote whenever they interacted with the government—when obtaining or renewing a driver’s license, for instance. It would go a long way toward getting voters onto the rolls and keeping those rolls updated when people move. And it would have ripple effects because we know from research that once someone votes, they tend to keep voting.”

Next, Ansolabehere suggests finishing the work started by the Help America Vote Act. A national voter list integrated from the state databases mandated by HAVA would streamline voter registration and reduce the incidence of duplicates. “You do see people registered in New York and Florida,” he explains. “They live half the year in one place, half the year in the other, and just assume it’s okay to vote in both. A national list would help address that problem and address systemic inequities by ensuring that every eligible citizen has access to the ballot. And the thing is, it already exists. Private vendors pull it together from the state lists. Academics and political parties use it for research all the time. It’s a small administrative step for the government to create it.”

Ansolabehere also calls for increased federal investment in studies of election administration. He envisions a dedicated division within the National Science Foundation focused on election integrity and accessibility, which could provide valuable data to state and local election officials. “It would make a big difference to the way that social scientists could help inform the decisions that counties and states make,” he says.

Finally, Ansolabehere proposes the establishment of a national election report that includes certified vote counts from every precinct in the US. “This report would enhance transparency and provide a reliable data backbone for the electoral system,” he says.

Ansolabehere contends that these reforms are practical, low cost, and relatively easy to implement. The real challenge, he acknowledges, is changing the country’s political culture so that improvements can be made. “There’s something about our politics right now that is not accepting of loss,” he says. “If you look at our government over the last 25 years, it flips back and forth between the parties. It’s often divided so even if you lose the White House, for instance, you’re never totally out of power. That’s an important thing to keep in mind.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast