From Possibility to Public Policy

Tyler Simko uses data science to make voting and education more fair

As President of the Board of Education in his hometown of South Amboy, New Jersey, Tyler Simko negotiated the complexities of educational policy and budget allocations while engaging with stakeholders in his community. Elected to the board while still in his twenties, he discovered early on the power that local officials have to effect change in the lives of citizens.

“Serving on a school board has a much more direct impact than most academic work,” Simko says. “Academics often study things in the abstract and try to make generalizable arguments. That’s important work but it’s different from putting those insights into practice.”

Simko, who graduated last May with a PhD in government, combined research with action in his years at Harvard’s Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (Harvard Griffin GSAS). Now, as then, his goal is to bridge the gap between possibility and public policy, making innovative use of computer algorithms and machine learning to address electoral issues like partisan gerrymandering as well as larger concerns like de facto racial segregation in public schools.

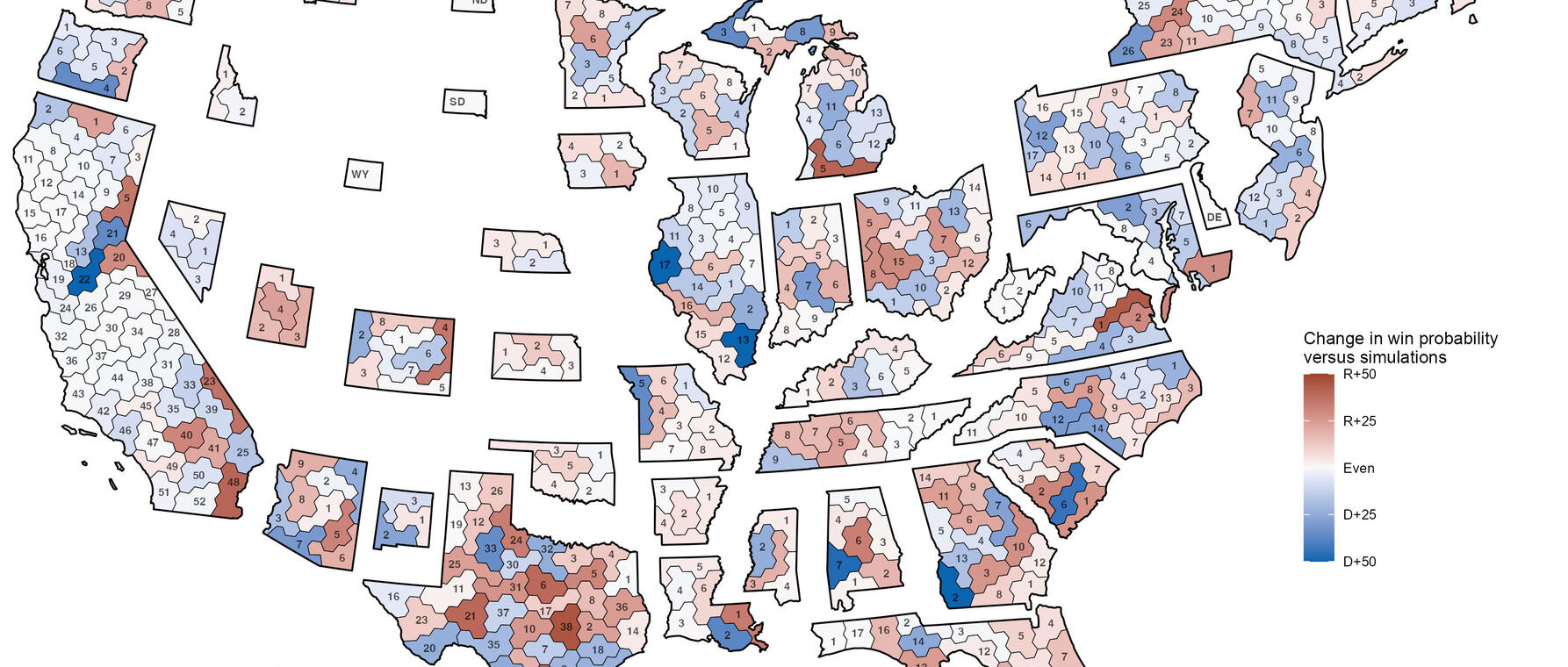

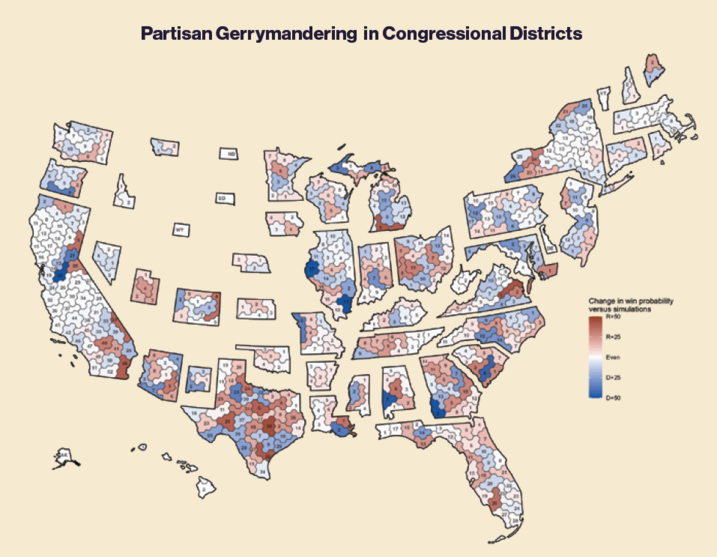

Sounding the ALARM on Gerrymandering

As a founder of the Algorithm-Assisted Redistricting Methodology (ALARM) Project, Simko collaborates with Professor of Government and of Statistics Kosuke Imai, PhD ’03—as well as students from Harvard’s graduate schools, Harvard College, and local high schools—to dissect gerrymandering, the partisan manipulation of electoral boundaries, through the use of powerful computational tools (see “Partisan Gerrymandering in Congressional Districts” model below). Some of the software the group has developed—including a package of tools called redist created in collaboration with Imai, Harvard Griffin GSAS student Christopher Kenny, alumnus Cory McCartan, PhD ’23, and research scientist Ben Fifield— is being used for research, litigation, and policy across the United States and in countries like Japan.

“We use the redist software to create alternative districts that follow state and federal requirements, like Idaho’s rule that congressional districts with multiple counties should connect based on the interstate highway system,” Simko says. “We then evaluate outliers by comparing the real, enacted plans to a distribution of simulated plans the state could have used.”

I use algorithmic tools to transparently evaluate many possible [redistricting] alternatives and characterize when and where policies can be effective.

These sampled plans can serve as a baseline for nonpartisan redistricting, says Professor Imai. “If the enacted plan favors one party, it serves as empirical evidence for partisan bias,” he explains. “We can use these algorithms and empirical evidence to help policymakers figure out the best policy.”

The ALARM team’s algorithm has already helped courts in states like Ohio and Pennsylvania decide whether enacted redistricting plans have a significant partisan bias. ALARM’s tools have also been used at the US Supreme Court level in the Alabama racial gerrymandering case Allen v. Milligan, which reaffirmed that a core portion of the Voting Rights Act can be applied legally to redistricting. In collaboration with Harvard Griffin GSAS student Emma Ebowe and Harvard College student Michael Zhao, the group is now studying reforms that could lead to fairer congressional districts.

“The ALARM group at Harvard has been a perfect way to combine my passion for policy impact with research,” Simko says.

Taking the LocalView

While doing work that has a national impact, Simko is still focused on the local level. He points out that local governments often have the greatest influence on the dayto-day lives of citizens. City councils and planning boards across the country have extensive power over issues like land use, education, and public health. But because power is so decentralized—and local journalism is vanishing—few largescale data sources on local policymaking are easily available to researchers, academics, journalists, and the public.

To bridge the information gap, Simko and Soubhik Barari, PhD ’23, launched LocalView, which uses computational tools to collect hundreds of thousands of meeting videos from local governments across the United States. “LocalView enables researchers to use the text, audio, and video data from these meetings to answer all kinds of important public policy questions,” Simko says. “Others, like journalists and the public, can use the data to understand what conversations are happening in communities across the country.”

In collaboration with Professor Rebecca Johnson of Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, LocalView recently expanded to collect over 100,000 videos of school board meetings around the US. “We aim to increase transparency, informed decision-making, and real-world impact,” Simko says.

Taking on Segregation in Schools

Because national politics and legislation dominate the headlines, people are often surprised, Simko says, by how much influence local officials can have over their lives. “School boards approve the curriculum, set the budget, choose the textbooks, and negotiate union contracts with teachers and other district staff. They often have a low profile but are very powerful.”

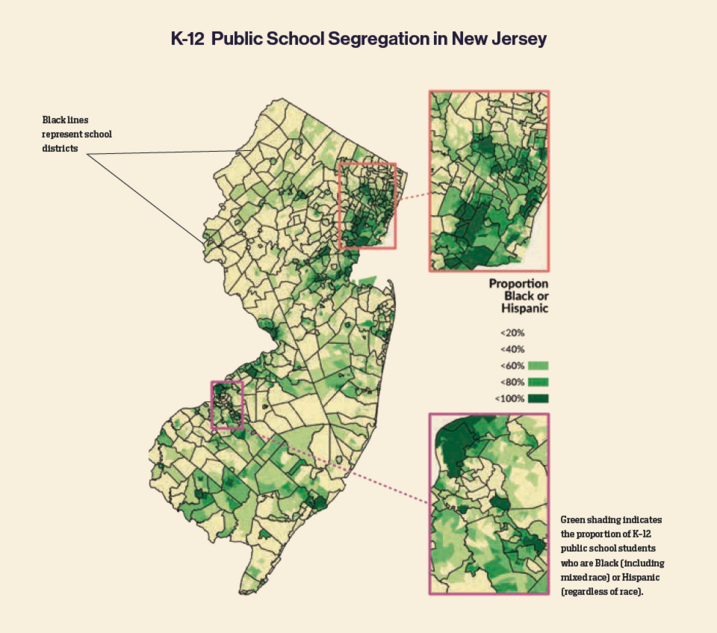

In New Jersey, as in many states, the lines drawn on maps have far-reaching consequences for educational equity. While de jure segregation was outlawed after the US Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, de facto racial segregation persists across the US, fueled by zoning patterns and residential choices (see “K-12 Public School Segregation in New Jersey,” page 20).

“New Jersey is one of the most racially and ethnically diverse states in the country, but residential segregation is also strong,” Simko says. “Like several other states, New Jersey generally divides school districts by town, which are often highly segregated. These boundaries also often divide homes that are more expensive from those that are more affordable.”

Simko cites the example of the small, affluent community of Glen Ridge, New Jersey. “There’s no legal requirement that low-income students can’t attend school in Glen Ridge, but low-income families are effectively priced out of living in town,” he observes.

The situation has given rise to debates about how US public schools draw their district lines. It’s also sparked lawsuits like Latino Action Network v. New Jersey, with plaintiffs claiming that the state has failed to remedy segregation caused by school districts and seeking to break the boundary lines in the name of equity. The challenge for those bringing suit, however, is to find alternative ways to draw the boundaries. “It’s not clear how districts could be redesigned to be more racially or socioeconomically integrated without increasing other constraints like student enrollment and travel time,” Simko says.

While it is difficult to imagine state officials using the algorithms directly to redraw school district lines, Tyler’s results make it vividly clear that it is politics and not practical considerations that stand in the way.

To address the challenge, Simko uses computational algorithms to redraw school districts according to different guidelines and then compares how each would change outcomes like racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic segregation. “For example, states could keep school district lines the same and reassign students to different schools,” Simko explains. “Or states could redraw the district lines entirely. States could even draw school districts at the county or regional level like they do in much of the South.”

Simko says it’s hard to know in advance which approach might work best in a particular setting because of logistic constraints—say, the number of existing schools—and the geographical distribution of students. “That’s why I use algorithmic tools to transparently evaluate many possible alternatives and characterize when and where policies can be effective,” he says.

Henry Lee Shattuck Professor of Education Martin West, PhD ’06, says that Simko’s algorithms reveal just how much progress could be made toward desegregating schools simply by redrawing district boundaries. “In New Jersey, racial segregation could be cut nearly in half even without requiring students to travel farther to school or the construction of new facilities,” he says. “While it is difficult to imagine state officials using the algorithms directly to redraw school district lines, Tyler’s results make it vividly clear that it is politics and not practical considerations that stand in the way.”

Simko says he and his colleagues are not proposing to simply turn the school districting process over to algorithms, no matter how well-intentioned their designers may be. “These tools are not meant to be prescriptive,” he says. “Complex policies like school assignments should ultimately be decided in conversation with stakeholders like district officials, families, and staff. However, these tools allow us to make it very clear what the possibilities are under different policies compared to where we are today.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast