Insecurity and Democracy in Haiti

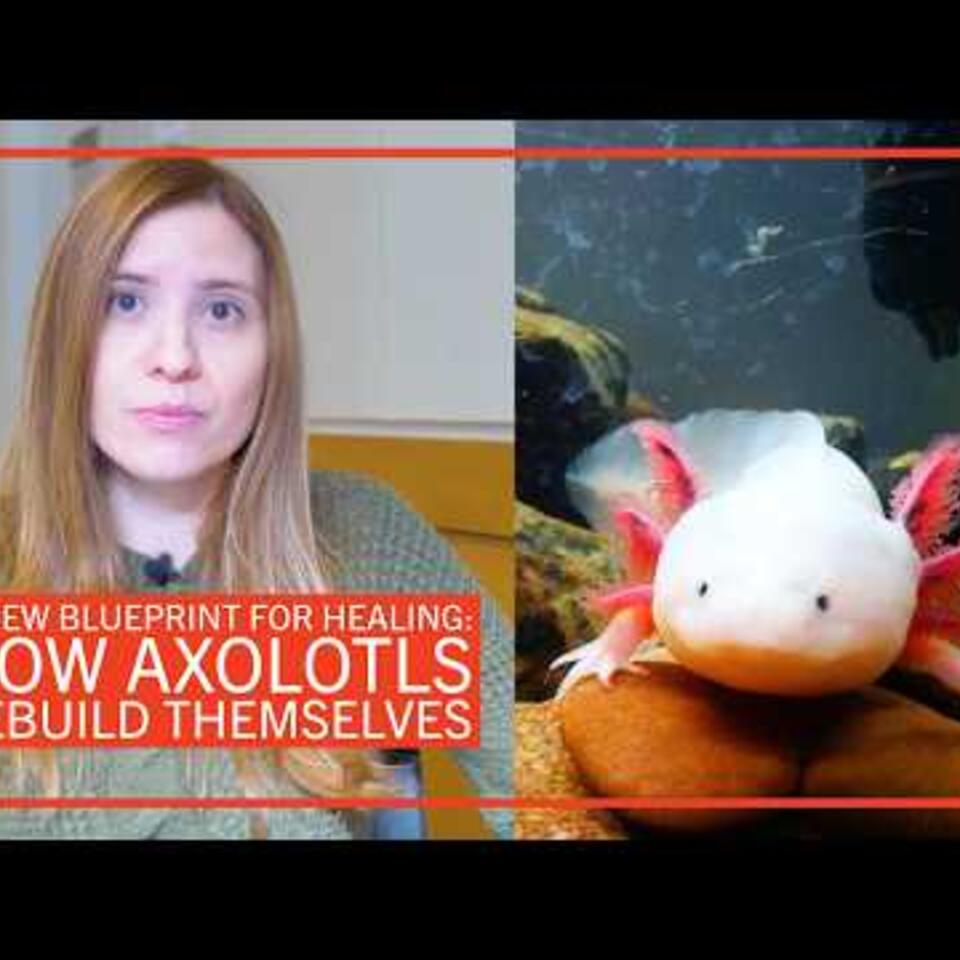

Erica Caple James, PhD '03, on the roots of the Caribbean nation's current unrest

Erica Caple James, PhD ’03, is a medical and psychiatric anthropologist whose first book, democratic insecurities: violence, trauma, and intervention in Haiti, documented the psychosocial experience of Haitian torture survivors targeted during the 1991–1994 coup period, analyzing the politics of humanitarian assistance in “post-conflict” nations making the transition to democracy. Currently a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, James outlines the roots of the country’s current unrest and says that ultimately, stability and security must come through governance that is accountable to Haiti’s people.

What does the Creole word ensekirite mean?

In a word, “insecurity” but of a particular kind. It’s very much like what the social scientist Anthony Giddens calls ontological insecurity—insecurity at the level of being from one moment to the next. Many in Haiti can’t assume a normative level of security from the built environment, social institutions, or family—none of the aspects of life that help humans develop psychologically and otherwise. Ensekirite in Haiti plays out in almost every area of life— including the physical bodies of the people there. Almost invariably, when Haitians described ensekirite and outer social space to me during my research, they also linked it to back pain, frequent headaches, and stomachaches. Their psychological experience had been somaticized: fear was ar ticulated and experienced in the body. It was almost embedded at the cellular level.

How did it start?

A native Haitian person would understand ensekirite specifically as connoting political and criminal violence between 1991 and 1994 after the coup that overthrew then-President JeanBertrand Aristide, but it began under the hereditary dictatorship of the Duvalier family that ruled Haiti from 1957 until its overthrow in 1986.

After his election in 1957, Francois Duvalier—“Papa Doc”—declared himself president for life and established a paramilitary force, the Tonton Macoute, to consolidate power. At first, it targeted more elite families that tended to be of mixed heritage. Then the use of repression spread to the general population and became indiscriminate, extending to women, children, and the elderly—populations that were formerly considered untouchable or innocent. The strategy was to control everyday life through a sort of violence that violated ethical and moral norms. Keep in mind that the government of Haiti throughout this time was viewed as a friend to the United States, which felt that its business interests benefited from having a strong authoritarian leader in control.

Ensekirite in Haiti plays out in almost every area of life, including the physical bodies of the people

The election of Jean-Bertrand Aristide as president was a moment of hope for Haiti. Then the coup you mentioned forced him to flee in 1991. In 1994, US and UN forces intervened to provide aid and restore democracy. Why weren’t these efforts successful?

The way that US aid was distributed was often governed and structured by a specific goal that was intended to benefit US business interests abroad. International development assistance was a means to create favorable economic relations, so the institutions supported didn’t necessarily have the autonomy, sovereignty, or authority of Haiti as their primary goal. Additionally, aid was funneled through so-called independent institutions—nongovernmental organizations—because it was thought that Haitian institutions of governance could not be trusted. These programs usually had a grant cycle—I call it a grant economy—in which the provision of aid was intended to meet particular deliverables. And so, whether it was a citizenship education initiative or a police-community relations program or, in rare cases, housing, the gaze of the person in charge of the funds was back to the donor and less to the people they were meant to serve. The fulfillment of the deliverable was, in part, the goal—along with the hope of renewed funding.

The second iteration of the US Agency for International Development-supported Human Rights Fund, for instance, aimed to promote human rights and democracy and also to reduce the negative psychosocial symptoms that Haitian victims of human rights abuses experienced. During my research, I found that the process of providing psychological support was often shaped by the need to make it empirically legible to the larger donor institution. The need to manage funds and to fulfill a certain set of results within a specific grant cycle or calendar put a tremendous amount of pressure on those delivering aid. But the time frame didn’t necessarily accord in any way with the path of Haitians toward greater security, lower symptomatology, greater capacity to find stable employment, etc. And, of course, this all occurred in the larger context of ensekirite.

Is there any end in sight to the extreme unrest in the country?

I think the biggest challenge is disarmament. If the gangs don’t disarm then there will be no ability to create conditions in which folks are not afraid of kidnapping or violence. There’s the possibility of integrating the gangs into civil society as political actors, but, again, are they going to remain armed? There was an effort to incorporate gang members into the national police force in the 1990s and it created divisions and conflicts that recurred for years afterward. There needs to be a Haitian-initiated plan for security and the sustainability of democracy that is supported by the population. That’s the best way to build institutions that can move beyond governance by force and build a civil society.

Curriculum Vitae

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Professor of Medical Anthropology and Urban Studies, 2023-Present

Associate Professor of Medical Anthropology and Urban Studies, 2017-2023

Assistant/Associate Professor of Anthropology, 2004-2017Harvard Medical School

Lecturer, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, 2015-2017Harvard University

PhD in Social Anthropology, 2003Harvard Divinity School

MTS, 1995Princeton University

AB in Anthropology, 1992

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast