Go with Your Gut

Why do we need a gut microbiome? And is there really a gut-brain connection? PhD students Cary Allen-Blevins and Vayu Maini Rekdal share the science behind the "healthy gut" headlines.

Before you pick up that $30 bottle of probiotics, listen to PhD candidates Cary Allen-Blevins and Vayu Maini Rekdal. It’s true that healthy bacteria make for a healthy gut – but scientists are still learning about how microbes help us break down our food – from our “first food” (breast milk) to meat and veggies.

Interview Highlights

"Plants are brilliant chemists. They produce a lot of different interesting molecules just regular, you know, plants that we consume every day. A lot of these molecules are thought to account for the health benefits of plants." - Vayu Maini Rekdal, PhD candidate in Molecular and Cellular Biology.

"We have this kind of negative bias about bacteria. So a lot of times we think of germs. But actually, for the most part, they're just trying to survive and reproduce like any other animal is trying to do." - Cary Allen-Blevins, PhD candidate in Human and Evolutionary Biology.

Full Transcript

From the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, you’re listening to Veritalk. Your window into the minds of PhDs at Harvard University. I’m Anna Fisher-Pinkert.

Last week, we spoke with Nina Gheihman about the cultural entrepreneurs who are promoting “plant-based diets” to get people to eat less meat. Nina pointed out that there are all these environmental benefits to eating plants, but eating plants is also good for our bodies.

Vayu Maini Rekdal: Plants are brilliant chemists. They produce a lot of different interesting molecules just regular, you know, plants that we consume every day. A lot of these molecules are thought to account for the health benefits of plants.

AFP: That’s Vayu Maini Rekdal, and h's a PhD candidate in Molecular and Cellular Biology at Harvard. Vayu has a background as a chef and he actually worked for Ferran Adrià, the famous Spanish chef whose restaurant, El Bulli, was considered to be the best in the world. But now, he's trying to figure out why we get nutrients from fruits and vegetables.

VMR: My research has focused partly on understanding how these molecules in plants are metabolized by gut microbes as kind of a way to better understand nutrition and health benefits of plant foods, which most people agree are, you know, very good for the human body.

AFP: So, here’s the crazy thing-- we don’t just digest food with our organs. There are actually trillions of microbes in our guts that help us process food. And, today on Veritalk, we’re going to try to figure out what a healthy gut looks like, and what exactly all those trillions of microbes are doing in there. Now, if you want to hear more from Vayu, you're going to have to tune in to a very special episode on another podcast, Proof, from America’s Test Kitchen. And, I’m going to talk more about that at the end of this episode. But for now, I’m going to introduce you to another researcher at Harvard.

AFP: What did you have for breakfast this morning?

Cary Allen-Blevins: I did not have breakfast.

AFP: OK. Describe your favorite meal.

CAB: Wow. Yogurt. I really like yogurt.

AFP: Really?

CAB: Yes. It's got nice microbes in it. It's tangy. It's got fat. It's good.

AFP: I like that you went with a microbe-heavy meal.

CAB: Of course! Absolutely.

AFP: That’s Cary Allen-Blevins. And aside from being a big fan of the microbes in yogurt, she’s also a PhD candidate in Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard. For the last couple of episodes we’ve been talking about food and culture: all these cool variations in what people choose to eat around the world. But before we can cook a meal, before we can reach out and grab a handful of Cheerios, before we can even chew, we still need nutrition. And until very recently in human history, babies' nutrition came from one place: breast milk. And that’s what Cary studies.

CAB: I study how breast milk composition affects the bacteria that live in the infant gut and what type of effects that might have on the infant.

AFP: The first thing I asked Cary: Why did humans evolve to lactate in the first place?

CAB: So humans didn't evolve this independently, right? All mammals do this, and we really have to take a very big step back to the Paleozoic. And there was a group called amniotes, which basically means they can lay eggs on land, and they split into two groups called synapsids and sauropsids. Synapsids eventually lead to mammals. Sauropsids eventually lead to reptiles and birds. And these synapsids were likely laying eggs that were leathery and soft, so more like a sea turtle’s eggs than like a hard chicken egg. And when you lay those types of eggs on land, you still need to hydrate them and protect them from bacteria and other microbes that might be around them. So lactation likely initially started as a modified sweat gland secreting water and immuno factors or immune molecules to protect those eggs on land. And then eventually it evolved into the complex system that we see in mammals today. But you can kind of see a little bit of this in a mammal that is the platypus because it actually doesn't have nipples. It has milk patches where it kind of just excretes milk onto its underside and then the young actually lap it up. You can also see this a little bit in humans today with colostrum, that first milk that comes out of the nipple, and that is really rich in proteins and immune molecules to protect the baby.

AFP: So lactation is a great way to get water and nutrients into an infant without worrying about the bad microbes that could be living in dirty water or rotting food. But, it’s also incredibly taxing for the lactating parent.

CAB: One of the reasons it's so costly is that the mother's body is basically having to make this food for the infant from her own fat stores, from the nutrition that she is taking in. So, normally, if you're not lactating, whatever you eat is consumed by your own body and by the microbes that live in your body, so you are getting energy from that. But when you're lactating, that energy is also going towards making milk for the baby and that milk in humans is full of things like lactose, carbohydrates, fats, proteins, minerals, immune molecules, hormones, and even bacteria.

AFP: Remember that there are trillions of microbes in your gut right now digesting whatever you had for lunch.

CAB: There is about a 1 to 1 ratio of bacterial cells to human cells just in the body as a whole. There's almost as much bacteria as there is you in your body.

AFP: And that’s an important thing to know to understand why breast milk is so good for infants.

CAB: Human milk has these special sugars in it called human milk oligosaccharides. Moms produce these sugars. All animals produce milk sugars in different forms. Humans are particularly special because we produce a very large number of them and a wide variety of them and different moms produce different ones. And then once those sugars get to the gut they are not digested by the infant. They get to the gut. They can either protect the baby against pathogens by acting as decoys for them or they can be metabolized by the bacteria in the infant gut. And once that metabolism occurs, the bacteria ferment these sugars, then these molecules called short chain fatty acids are released, and those can actually be used by the baby as energy for either a very localized cell, so energy for the cells that line the colon, which is very important to have a nice tight thick colonic lining, or they can be used as energy for other cells around the body.

AFP: So, breast milk protects babies from bad bacteria, and feeds good bacteria that help the baby grow a healthy colon. Feeding those good gut microbes is essential for good health.

CAB: If you did not have gut microbiota in your system, then a lot of things go really haywire. So we do experiments with germ-free mice a lot in this field. And you see how different germ-free mice are from mice that have been colonized with a normal microbiota. There are differences in immune regulation. So the gut microbes are really training the baby's immune system. There are differences in behavior. So that's one of the reasons why people started getting really interested in how microbes might affect personality and behavior. There are really a lot of differences between mice that have never been exposed to microbes and mice that have normally been exposed to microbes.

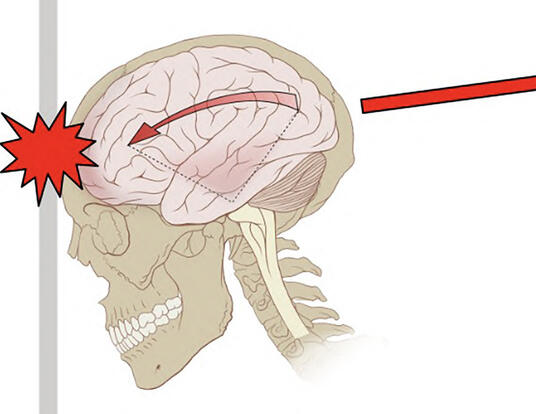

AFP: The gut-brain connection is another way that microbes help us out. Scientists have found that some gut bacteria produce neurotransmitters, like serotonin and dopamine, that impact our mood.

CAB: What we don't know is how these things are interacting with our brain. So in some studies we see that these neurotransmitters seem to travel along the vagus nerve, which is the nerve that controls your digestive tract and it goes to your brain. That's one way that things could be interacting. There's also a possibility that bacteria are producing neurotransmitters in your gut, and then that's going directly into your blood or other pathways to your brain. It's a really fascinating field. It's also very young, so there are lots of unanswered questions.

AFP: I’ve you have your credit card out right now and you’re googling the nearest store that will sell you a bottle of probiotics to cure your anxiety and depression, Cary has some bad news.

CAB: When we look at human studies and we take people who have depression or anxiety and we look at what type of microbes are living in their guts, you see differences. But then the question becomes, are their microbes different because they're depressed or anxious, so that's affecting their gut, or is the difference in microbes causing them to be depressed or anxious. So we're not really sure which way those arrows go yet. There also could be a little bit of both going on. And in some instances we have identified particular species [of bacteria] that seem to be having effects in certain diseases states. But we also don't know, once we've identified a species that seems to be causing something or is associated with something, what dosage do we need to get that into people. And is that going to affect all people in the same way? Is that the only species that's having that effect? Once it's in the actual gut environment with all of these other species, is it still going to have the same effect? Is it going to be different? Is something else going to have an effect to that point? So it's a really complicated system to try to look at individually, and I think unfortunately a lot of people are trying to take advantage of this by coming up with these probiotic products that promise these big results by feeding you one strain of a bacterium. But it's just so unlikely that those are going to have actual effects.

AFP: Your gut is an environment. Like a watering hole in the savannah, or an ice floe in Antarctica. Dropping a random strain of bacteria into your gut could be kind of like dropping a zebra in the middle of an iceberg and expecting it to thrive.

CAB: Yes, that is a great analogy. It could be like you know putting yourself on Mars and thinking you're just going to live in a normal environment that you would find on Earth. There are just so many different variables that need to be accounted for.

AFP: So, fistfuls of probiotic pills are probably not effective. But what about yogurt?

CAB: It depends on a few factors. So it depends on if you're eating a true live yogurt or not. So if the bacteria is actually still alive in that yogurt, or if the bacteria have just been used to make the yogurt and now the bacteria are dead. It also depends on how resistant your own gut microbes are to new things coming in. So when we think of community ecology, we think of resistance and resiliency. So resistance is how well the ecosystem maintains its normal species load, and then resilience is how well it can bounce back after something's happened, like a forest fire or something like that. So if you have a really resistant community, then the microbes that you get from food are potentially just going to pass right on through. And part of that is because your gut is basically like a system of ecological niches. Bacteria are taking up space, they've already kind of staked out their spot, and they're like: I'm here, I'm going to eat this thing, I'm going to be attached to this lining, or I'm going to hang out in this space between the linings, you know, but this is my spot. And when you have something else that comes in, if all of those spots are filled, then they're going to have to compete with the bacteria that are already there in order to fill that spot. So if you have a resistant community, those bacteria are not going to be able to outcompete the things that are already there, and that typically means you have a healthier gut.

AFP: After spending a lot of time with the creatures who live in our guts, Cary has two things that she wants us to know. First, don’t spend all your money chowing down on probiotics.

CAB: I would like to dispel this idea that probiotics in any form are fantastic for you. Probiotics in the U.S. market are almost completely unregulated. And so you end up with these probiotic products like probiotic chocolate bars and probiotic tortilla chips. And I just look at those products and it hurts my heart deep inside because the likelihood of them doing anything is just very small.

AFP: And, second, stop treating bacteria like second class citizens.

CAB: We have this kind of negative bias about bacteria. So a lot of times we think of germs. But actually, you know, bacteria for the most part they're just trying to survive and reproduce like any other animal is trying to do or any other life form. Really there are more bacteria that are neutral or even beneficial than there are ones trying to harm you in any way. So I want people to have a better sense of there are lots of really cool bacteria and lots of things that aren't going to put you in the hospital and embrace that.

AFP: Even though Cary spends a lot of time in the world of microscopic creatures, she also wants people to know that she sees the very tough decisions that us human-size creatures have to make. And that includes breastfeeding.

CAB: For women who want to breastfeed, I think that's great and do that. For women who do not want to breastfeed, that's also their decision. And you have to make the decision that's best for you and your child. So there's an expression that a fed baby is the best baby. One of the reasons why I'm interested in doing the work that I do is because breastfeeding can be a very difficult process for moms. The World Health Organization recommends that babies are exclusively breast fed up to six months. If you don't have the cultural resources around you to support that, it's very difficult to maintain that. And even if you are middle class and have a good job, you might not have pumping facilities, you might not have time. There are a lot of things that can get in the way. So one thing that we can potentially do is figure out what milk is doing for babies so we can design better formulas and give moms more options.

AFP: Figuring out how to feed a new baby is hard. And the tough choices don’t stop when your child moves on to solid foods.

Next week, we’re going to take a look at the intersection of nutrition, class, race, and the obesity epidemic. Before I go, I want to tell you about how to listen to more cool stories about microbes from Vayu and Cary. Later this month on the podcast Proof, there will be a special extended version of this episode with even more insights into how microbes help us to digest our favorite foods. Proof is a podcast from America’s Test Kitchen hosted by Bridget Lancaster. In every episode, Proof takes on a new food mystery and asks big questions about the hidden backstories behind the things that you eat and drink. The second season of the show drops on May 23rd. And to listen, you can search for “Proof” on your favorite podcast app and hit “subscribe.”

Veritalk is produced by me, Anna Fisher-Pinkert.

Our sound designer is Ian Coss.

Our logo is by Emily Crowell.

Our executive producer is Ann Hall.

Special thanks this week to Cary Allen-Blevins, Vayu Maini Rekdal, the Harvard Museum of Natural History, and the PRX Podcast Garage.

Logo by Emily Crowell

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast