Final Frontier

Harvard Horizons Scholars advance the boundaries of knowledge—and imagination—in search for new worlds

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

At night, the sky above the Colombian coffee farm where 2022 Harvard Horizons Scholar Juliana García-Mejía grew up teemed with stars. On many evenings her uncle, an anthropologist with a love of astronomy, would gather all the cousins together to gaze up and think about the universe.

“He started asking us questions such as ‘Do you think that the existence of the moon is important for life on earth?’” remembers García-Mejía, who’s now working toward her PhD in astronomy. “I was absolutely enthralled. I really could not get enough of those conversations. It became this love for science that we shared.”

Fellow Harvard Horizons Scholar Karina Mathew also thought about what lay beyond the boundaries of Earth’s atmosphere when she was growing up. A Russian immigrant schooled at home by her parents in California, she read books and watched documentaries like Through the Wormhole hosted by the actor Morgan Freeman that investigated the mysteries of the universe. A member of a creative family, Mathew worked on a science fiction novel, requiring her to explore more deeply the topics she studied.

"I was fascinated by the perils, possibilities, and new opportunities for investigation offered by emerging technology and science," she says. "One of these questions was whether life—human or alien—could thrive on other planets, and what that would mean for us."

Although García-Mejía and Mathew study very different fields today at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the two share a preoccupation, reflected in their research, with the prospect of worlds beyond our own. Both are advancing knowledge in ways that could change the way we think about the search for extraterrestrial life. And both are doing work that forces us to reconsider the place of humanity in the stars—and in our own stories.

Like the Earth, [more temperate planets] likely have orbits longer than 28 days. So, [NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite] could miss a lot.

—Juliana García-Mejía

Tierras and TESS

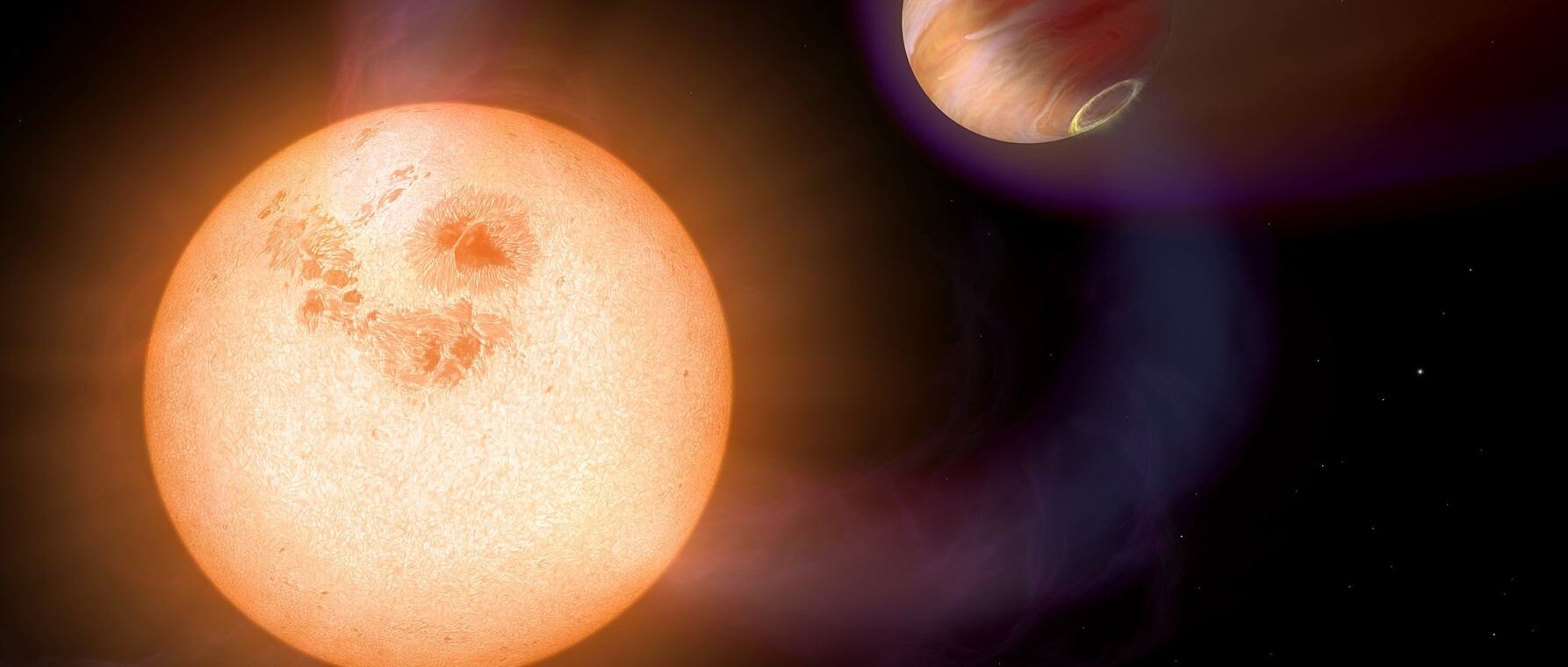

García-Mejía’s enthrallment with the night sky has led her to design, build, install, and now test a new instrument to search the heavens. This work is the topic of her Harvard Horizons project, “The Tierras Observatory: An Ultra-Precise Photometer to Characterize Nearby Terrestrial Planets.” Her ultimate goal is to identify worlds that might support life.

The project is in part inspired by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) launched in 2018. At its apogee, the satellite’s elliptical orbit takes it about as far from Earth as the distance to the Moon. There, the space-based observatory trains its camera on a part of the sky, taking pictures rapidly and continuously. In two to four years, TESS is expected to capture images of around 200,000 stars as well as some of the planets that revolve around them.

TESS is very powerful but it’s still only one satellite. It can focus on each sector for only 27 days if it is to achieve its goal of a nearly all-sky survey within four years. García-Mejía says that’s not enough time to capture planets that are distant from the star they orbit—and thus, more likely to support life.

“TESS uses the transit method of detecting planets,” she explains. “A planet orbits a star. When it comes between the star and the observer—in this case, TESS—the amount of light we measure from the star diminishes. That’s how we detect planets. But planets that are more temperate are more distant from the star. Like the Earth, they likely have orbits longer than 28 days. So, TESS could miss a lot.”

To fill this gap, García-Mejía founded the Tierras Observatory at the top of Mount Hopkins in Arizona. Using cameras twice as sensitive as those in most “state of the art” ground observatories combined with other innovations—a custom filter that minimizes the negative effects of the atmosphere on astronomical observations; four lenses that expand the observatory's field of vision—Tierras will look more closely at the systems identified by TESS in search for the smallest and most temperate planets, as well as for hints of any moons.

Professor of Astronomy David Charbonneau, García-Mejía’s advisor, says that the optics she developed at Tierras are an important advance for their field.

“Juliana's telescope is designed to achieve a spectacular sensitivity,” he says. “It weeds out most wavelengths of light, leaving only those that are not affected by the weather. It increases the field of view so that she can study many stars at once. And it's fully robotic, ensuring she is gathering data reliably night after night.”

Charbonneau says that one of the most exciting possibilities at Tierras is not the discovery of another Earth, but a moon of a planet orbiting another star. “The existence of the Earth's moon tells us about the formation of our planet and is likely essential for making Earth habitable,” he explains. “It's very important to know whether rocky worlds orbiting other stars also have moons.”

García-Mejía says she aims to build astronomical instruments that enable research on the question of whether humans are alone in the universe. The first step in that quest is to find places where there could potentially be life as we know it on Earth. “That means looking for planets that are very similar to the Earth,” she says. “Those tend to be the smallest planets, so you need the most precise and powerful instruments to be able to identify and characterize them.”

A Messenger from Afar

Moons, planets, and other heavenly bodies were a source of fascination for Karina Mathew as she forged a path to GSAS. After completing her K-12 education at home and online, she attended community college to develop the academic record and training necessary to apply as a transfer student to a university. There she took a series of astronomy courses that left her with goosebumps as she leafed through the textbooks.

“I took a course called ‘Life in the Universe,’” she says. “I got chills just thinking about how big the universe is, the variety of possibilities. I took another course on how different cultures over time studied the universe. It was really exciting.”

Mathew toyed with the idea of being an astronomer but decided that the questions she found most interesting concerned the way that humans related to the stars and planets, not the phenomena themselves. “How does the way we think about the larger universe have an impact on humans individually and culturally?” she asks. “How can that expand our consciousness and awareness of what it means to be human and what it means to be a living being in a given world? My interest in those questions led me to the study of literature.”

Science fiction fills a gap until we find life in the universe. At its best, it helps us to think critically about what we’re looking for and how we’re looking for it.

—Karina Mathew

When she arrived at GSAS in 2018, Mathew was interested in studying representations of the scientific revolution in the works of early modern English literature. In the course of her research, she discovered 17th-century stories of lunar voyages and extraterrestrial beings. Around the same time, astronomers observed for the first time an interstellar object passing through the solar system. Named Oumuamua—a Hawaiian word meaning “a messenger from afar arriving first”—by astronomers, the size, shape, and behavior of the object were different than typical asteroids. Scientists didn’t quite know what to make of it.

Mathew was fascinated.

“I found myself comparing the early modern work and the recent discovery of an object that may or may not have originated from an interstellar civilization,” she says. “And as I began to compare these two, I also delved into a lot of contemporary science fiction which spoke more directly to contact with extraterrestrial life. That exploration took over my research.”

Mathew switched from being an early modernist to a scholar of 20th and 21st-century literature so that she could explore science fiction and other works that spoke directly to the experience of living in the contemporary world. Her Harvard Horizons project, “Imagining Extraterrestrial Contact,” is part of that effort to better understand what it means to be a human in a universe where we might not be alone. With the advancement of observational technology like García-Mejía’s Tierras telescope, the detection of extraterrestrial life is increasingly a possibility. And while scientists have long had a love-hate relationship with speculative fiction, Mathew says that they are in constant engagement with it as they search for extraterrestrial life.

“Astrobiologists, understandably, distance themselves from science fiction to maintain the reputation of their field," she says. "But many cite science fiction as an inspiration for their career and reference fictional works for different contact scenarios. So much of the landscape of this field is in the imagination—thinking of what we might or might not find. Science fiction fills a gap until we find life in the universe. At its best, it helps us to think critically about what we’re looking for and how we’re looking for it.”

Mathew says that in the search for life, science fiction plays a strong role in filtering what we see in the night sky. Embedded in those powerful stories, though, are human narratives that bear scrutinizing: the fear of the unknown—and a reckoning with the West’s history of colonization in H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, for instance. “Some of the science fiction narratives are shadows, not of the aliens out there, but the darkness of humanity here on earth,” Mathew says.

At the same time, Mathew points to examples of extraterrestrial contact stories that expand the boundaries of human imagination and enable us to think more openly about the search for life. One of her favorites is Annihilation, the 2014 Jeff VanderMeer novel in which four women cross the boundary into the mysterious Area X to investigate its potential threats to human health, the environment, and society.

“It’s an alien contact story that pushes us to rethink even the concept of the alien,” Mathew says. “It’s hard to understand what the entity that inhabits Area X even is. We don’t know where it comes from. We don’t know if it’s synthetic or organic. It can change and adapt—even use human language—but is it alive? Is it a force? This novel is an excellent case study in imagining what different material activity could look like.”

Journey Past the Earth as Center

The more time García-Mejía invests in the hunt for new worlds, the more she understands the challenges associated with defining the search in terms of how life emerged on Earth.

“We’re looking for planets about the same size as Earth,” she says. “In the very near future, we will have the opportunity to study their atmospheric compositions in search of methane, carbon dioxide, oxygen, etc. If those components exist in a proportion similar to those of Earth, we may be in a position to speculate about the existence of life—for example cells and bacteria, on those planets. That said, 2.5 billion years ago, the Earth's atmosphere had virtually no oxygen, rather than the 20 percent it has now. So, our current search parameters could make us dismiss an ‘ancient Earth’ altogether.”

Although the search for extraterrestrial life is often the subject of speculative fiction, Karina Mathew’s dissertation advisor Martin Puchner, the Byron and Anita Wien Professor of Drama and of English and Comparative Literature, says that these stories are ultimately about what it means to be human. And it’s in that context that they can shape the perspectives of scientists like García-Mejía.

“Many works of fiction use the scenario of contact with extraterrestrial life as an occasion to think about the difficulties we humans have to suspend human-centric expectations,” he says. “At other times, the extraterrestrial scenario raises questions about our relationship to earth’s environment. Speculative and science fiction can show how difficult it is to wrap our minds around the possibilities of seeing beyond our experience; a set of thought experiments in failure.”

García-Mejía echoes Puchner’s comments about the value of speculative fiction. A lover of stories like Frank Herbert’s Dune and Isaac Asimov’s Foundation, she thinks that literature can be a powerful way to experiment with the limits and definitions of life elsewhere in the Universe. “I am very excited to see how the places that we have to draw inspiration from, such as fiction stories, can open our eyes to new possibilities,” she says.

Speculative and science fiction can show how difficult it is to wrap our minds around the possibilities of seeing beyond our experience; a set of thought experiments in failure.

—Martin Puchner

Frank B. Baird, Jr., Professor of Science Avi Loeb, another of Mathew’s advisors, agrees that speculative fiction can enable scientists to think about their work in new ways. At the same time, he says it’s important for astronomers, astrobiologists, and others to be rooted in empiricism to continue advancing both human knowledge and the possibilities for the future.

“Knowing the constraints of reality and not hallucinating allows us to operate responsibly,” he says. “The philosophers who refused to look through Galileo's telescope because they ‘knew’ that the sun moves around the Earth would never design a rocket that would reach Mars because in their virtual reality Mars moved around the Earth.”

Mathew says her ultimate goal is to think about life, intelligence, and civilization more creatively and flexibly. She believes that, by engaging our imaginations, we can move beyond the restrictions of our technology and our human expectations.

“We need to be able to conceive of the fact that other life forms might think in very different ways,” she says. “If we're searching for signs of civilizations that communicate through linguistics, mathematics, or in ways that are recognizable to us as science or technology, we might miss out on some remarkable phenomenon. If we can get out of the mindset that human intelligence, human tools, and the human way of life are the pinnacle of evolution we might be better able to see what other fascinating forms of life might exist in the universe.”

Portraits by Stu Rosner; Photos courtesy of Juliana García-Mejía and WikiCommons

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast