Leading Learners through Loaded Conversations

With support from Harvard’s Bok Center, graduate student teachers make classrooms a place for open inquiry, constructive dialogue

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

I know indeed what evil I intend to do, but stronger than all my afterthoughts is my fury, fury that brings upon mortals the greatest evils.

—Euripides, Medea

In the ancient Greek tragedy, Medea, the titular princess has been abandoned by her husband Jason for Glauce, daughter of the king of Corinth. Enraged and condemned to exile, she engineers the agonizing murder of her betrayer’s new betrothed—and Glauce’s royal father who arranges the union. Then, to ensure her husband’s complete ruin, Medea murders her own children.

“Students have rightly asked me, ‘Why do we study works that deal with some very disturbing topics?’” says classics PhD student Alexander Vega, a teaching fellow who leads undergraduates through discussions of Medea and other Greek and Roman writings that contain controversial themes. “Revenge, infidelity, filicide, the oppression of women, even slavery—I’ve learned to acknowledge the challenging and disturbing aspects of ancient literature and present them as opportunities for discussion and critical engagement. We could omit certain parts of the story, but then we wouldn’t have a full picture of the cultures and worlds we’re studying.”

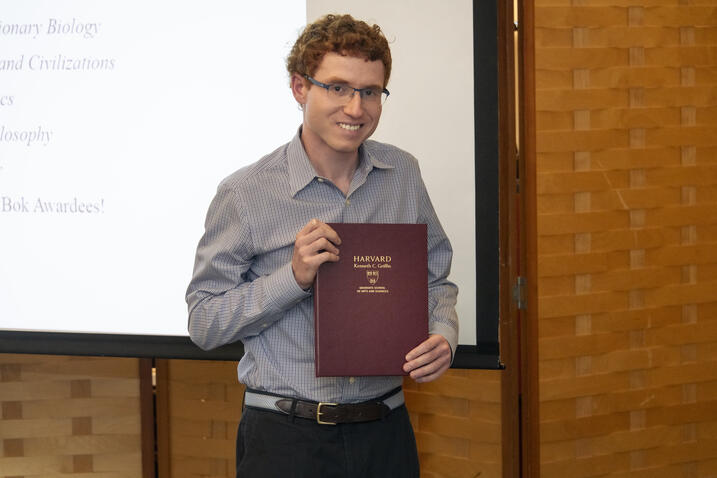

Open inquiry and constructive dialogue are central to Harvard’s mission of educating leaders who pursue truth and knowledge and work for a better world. But graduate student teachers like Vega, who facilitate these conversations, are made, not born. They are a product of the partnership between The Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (Harvard Griffin GSAS) and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, which, through rigorous training and development, produces classroom leaders who guide learners through the most controversial ideas and fraught topics—and, in so doing, acquire skills and experience that have value well beyond academia.

I’ve learned to acknowledge the challenging and disturbing aspects of [course materials] and present them as opportunities for discussion and critical engagement.

–PhD student Alexander Vega

Duty, Curiosity, Humility

The Bok Center is responsible for training instructional support staff for FAS courses, including teaching fellows, teaching assistants, and course assistants. Teaching fellows (TFs) are graduate students enrolled at any of the University’s Schools. Teaching assistants (TAs) have the same instructional responsibilities as teaching fellows but aren’t currently enrolled as students at Harvard. Course assistants are undergraduates whose role has a more narrowly defined scope than that of a TF or TA. Students at the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (Harvard Griffin GSAS) make up the bulk of the instructional support staff in FAS courses.

Harvard Griffin GSAS Dean Emma Dench says that, whether facilitating a discussion section or running a lab, the School’s students are on the front lines of teaching and learning at Harvard College. Dench points out that graduate-level research requires students to gather data, make arguments, and venture into non-obvious, non-consensus perspectives—precisely the kinds of skills and experience needed to foster open inquiry in college classrooms.

“You don’t get research degrees by jumping on bandwagons,” she says. “It’s pretty much impossible to get through one of our master’s or PhD degrees without challenging what your peers think—and without someone challenging what you’re saying. As such, our students can pave the way for undergraduates. Being able to have really open discussions where intelligent people have to disagree—and there are regularly at least two sides to every question, and often more than that—I see that as being really essential to the vibrancy of the classroom.”

Harry Tuchman Levin Professor in Literature, Professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, and Harvard College Professor Karen Thornber, the Richard L. Menschel Faculty Director of the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, says her staff teaches instructors to create a classroom environment where inclusive and rigorous dialogue can flourish and meaningful connections are made between instructors and students as well as among students themselves. The training begins with an understanding of the professional duty new instructional support staff have to all their students—whether they agree with their views on a topic or not. “If you frame things in this way—that your duty is to your students, not to a particular way of thinking—it becomes clear that you can’t allow one or two students to guide the conversation or set the agenda,” Thornber notes. “You really need to bring out multiple perspectives across your class.”

You don’t get research degrees by jumping on bandwagons. It’s pretty much impossible to get through one of our master’s or PhD degrees without challenging what your peers think—and without someone challenging what you’re saying. As such, our students can pave the way for undergraduates.

–Emma Dench

Dean of Harvard Griffin GSAS

In this context, the Bok Center asks instructional support staff to reflect on their teaching personas—the parts of themselves they bring to the classroom. These aspects could be obvious—what they say in class and how they express themselves overtly—but also more subliminal: the stickers on their laptops, how they chat or engage with students before or after class, and with which students they connect. “There are many aspects to a teaching persona one can’t adjust, like gender or national background or how we speak—which makes it all the more important to consider carefully those aspects that we can adjust,” Thornber says.

Bok training also emphasizes the importance of intellectual humility and curiosity. “Being curious enables us to be more open to different perspectives,” Thornber says. “If we’re curious, we’ll learn from people we disagree with rather than judging them. Humility forces us to acknowledge our limits—our limits in our knowledge and understanding. We want teachers who are very self-aware and also very open.”

Finally, the Bok Center works with instructional support staff to help them normalize the discomfort of challenging conversations. Thornber says it’s often instinctual for teachers and students to avoid conflict and view moments of disagreement in the classroom as a sign that something has gone wrong. In fact, it’s critical for students to challenge and critique each other’s ideas as part of the learning process. “This can be difficult because it needs to be done in a collaborative spirit of generosity and regard for each individual,” she observes. “So, it’s a fine balance—lively classroom discourse with respect, humility, and connection.”

A Professional Superpower

Dean Dench notes that teaching is a critical aspect of PhD students’ professional development, whether or not they choose to make their career in the academy. “I talk to a lot of our alumni, and teaching comes up in almost every conversation,” she says. “They can often cite very specific experiences in the classroom: ‘I was considered, in my finance or legal or public policy career, completely unique because I know how to draw in the perspective of the younger member versus the experienced member of the group. I know how to facilitate. I know how to get the best out of employees with a whole range of different perspectives.’ When they apply that to the world of work, it’s like a superpower.”

Thornber, a PhD alumna of Harvard Griffin GSAS, says that through teaching, graduate students learn to engage openly and professionally with others whose ideas may be quite different from their own.

“If you’re going to go on to be successful, whether in academia or any other field—and particularly in leadership positions—you need interpersonal skills that allow you to connect and engage positively with people, ideas, and actions that may be quite different from yours—or even initially repulsive to you,” Thornber says.

By navigating the waves of discomfort that go along with brave conversations, Vega says he gets to see what’s on the other side. He says that students often surprise him with their capacity to engage with even the most emotionally and morally challenging subjects.

If you’re going to go on to be successful, whether in academia or any other field—and particularly in leadership positions—you need interpersonal skills that allow you to connect and engage positively with people, ideas, and actions that may be quite different from yours—or even initially repulsive to you.

–FAS Professor Karen Thornber

Richard L. Menschel Faculty Director of the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning

“Studying something doesn’t necessarily imply endorsing it,” he says. “In my experience, students can separate their horror at certain views or depictions from their explorations of ancient cultures and ideas. When it came to Medea, students were fascinated to explore this character—to study her motivations and how she responded to the status of women in the ancient Greek world. That was one of the classes where the students were most engaged.”

Training for Every Teacher

The 2023 Final Report from the GSAS Admissions and Graduate Education (GAGE) Working Group singled out training as “imperative” for graduate student teachers. It called for pedagogical instruction to be required of all first-time teaching fellows, for course heads to mentor TFs, and for the fellows to receive ongoing training and support during the term.

Thornber says the Center is on its way to achieving the goals identified in the GAGE report. As a sign of things to come, she points to the undergraduate Program in General Education (Gen Ed). “We piloted required training with Gen Ed in January 2025, built into the contracts of their instructional support staff,” she says. “Virtually all of the more than 130 Gen Ed instructional support staff this semester received Bok Center training.”

When Thornber began as Menschel Faculty Director last July, only about 10 to 20 percent of new instructional support staff in the FAS received training from the Bok Center. Starting this fall, Thornber notes, and building on the Center’s success with Gen Ed, that will change. “Our goal is that all new instructional support staff assigned to FAS courses will receive training from the Bok Center,” Thornber says. “That’s 500 to 600 instructors. We’ll introduce the basics of teaching, the nuts and bolts, and then build toward more advanced skills. By fall 2026, we’ll scale up so that we are training all instructional support staff teaching in the FAS, regardless of their prior teaching experience. This will be a huge and necessary transformation.”

Matthew Sohm, PhD ’22, the Bok Center’s assistant director for civil discourse and classroom culture and a lecturer in history and literature, says the training will enable instructors to help students take intellectual risks and create an open classroom environment by understanding how different pedagogical tools might be used in a variety of situations.

“In our fall training for all new instructional support staff, we emphasize the learning objectives of a given section and discuss how to use different approaches in the classroom to achieve them,” he says. “We also provide instructors with strategies for managing some of the interpersonal challenges that teaching entails, whether in navigating teaching team dynamics or facilitating difficult conversations in class.”

Sohm says the fall training will give new instructional support staff hands-on approaches they can use to structure classes in the service of course goals, including interactive ways of learning that help students engage with viewpoints they might not agree with. Often, that means teaching instructors to push back on premature consensus.

“We emphasize it’s important to assume there are more opinions in the classroom than perspectives being articulated,” he explains, noting that anonymous polling can sometimes surface unvoiced opinions, but isn’t feasible to use in all contexts. “Because their obligation is both to the discussion and course material and to all their students, it’s important for instructors to actively offer alternative viewpoints, even and especially if they don’t know if anyone in the classroom will agree with them.”

“I’m so happy and grateful to Karen, Matthew, and the Bok Center for pursuing this priority so thoughtfully,” says Dean Dench. “We need to send graduate students into the classroom with training. It’s what’s fair for students, TFs, and faculty. That was something on which the entire committee for the GAGE Report was resolute.”

Vega says that the Bok Center’s support has helped him develop skills he can use in an academic setting—and beyond: the ability to communicate complex ideas clearly to people who may not have any background in a subject; to present material in creative ways that demonstrate its relevance; and to organize groups of people around a common goal. “Teaching is incredibly useful for storytelling, for marketing, for producing media—even things like public outreach. These skills transfer well to roles in business, law, nonprofits ... really any collaborative environment.”

Dean Dench agrees and says the Bok Center’s work—and that of graduate student teachers who enable civil discourse on the most charged topics—help Harvard Griffin GSAS realize its mission of educating thought leaders who contribute to a better world. “PhD students delve into complexity,” she says. “You can give someone with a well-trained research background 4,000 pages of contradictory material, and they can find a persuasive read—a breakdown of the major arguments, and why they matter. That’s powerful. Think about how that helps the world.”

Banner photo courtesy of Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast