Paying It Forward

2024 Centennial Medalists are distinguished by excellence as scholars and mentors

The members of the 2024 Centennial Medalist cohort—like those of the past 35 years—have defined excellence in their chosen fields. “All four of this year’s medalists have increased our understanding of life around us and saluted Harvard with their incredible gifts,” says David Staines, PhD ’73, a professor of English at the University of Ottawa and chair of the Graduate School Alumni Association Council’s Medals Committee. But, Staines says, the 2024 honorees—a writer and gay-rights activist, a sociologist focused on gender and women’s studies, a biophysicist, and an art historian—have something else in common as well: “Not only have this year’s quartet of winners given the world lasting knowledge of their disciplines, but they have also consistently inspired generations of scholars with their gift of exceptional mentorship.”

The Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences’ (Harvard Griffin GSAS) highest honor, the Centennial Medal has recognized some of the institution’s most accomplished alumni. By helping younger scholars find their feet, however, this year’s cohort earns distinction not only for its past contributions but also for its impact on the future. “They’ve all taken a personal interest in passing on their knowledge,” Staines notes. “So the advances they’ve made will grow exponentially in the years to come.”

Centering Dissenters

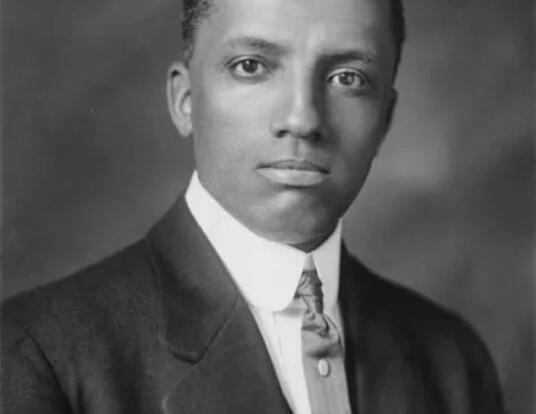

Now 93 years old, Martin Duberman knew he was different even as a child—albeit in a way that might surprise those who know him primarily as a gay-rights activist and groundbreaking historian of gay culture. “Different in the sense of being interested in learning and books,” he says. “By college, I had decided I wanted to become an academic, but I ran into considerable opposition on that from my parents,” both of whom could not afford college when they were Duberman’s age and considered graduate school excessive. “They thought I should be content with my undergraduate degree from Yale and making a career in my father’s dressmaking business,” he recalls.

To overcome their initial objections, Duberman wrote to Crane Brinton, a well-known Harvard historian and one-time chair of the Society of Fellows, to request an invitation of sorts. “I said I need a letter from you saying that as far as one can predict, I will have a bright future in the history department,” Duberman remembers. Brinton responded with a note that the young scholar was “our number-one choice.” Duberman’s parents relented.

Brinton’s prediction about Duberman’s chances proved spot on. “Martin has an incredible body of work in biography, playwriting, and fiction,” says Marcia Gallo, a former student of Duberman’s who is now an author herself and a professor emerita at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “And in addition to being the most encouraging and thoughtful adviser and mentor I could have imagined, he’s also an institution-builder and a philanthropist. In 1991, while at the City University of New York (CUNY), he founded CLAGS, the first ever center for lesbian and gay studies based at a university, and later founded two fellowships for LGBTQ scholars.”

In addition to being the most encouraging and thoughtful adviser and mentor, he's also an institution-builder and philanthropist.

—Marcia Gallo, Professor Emerita, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

After years of trying to “get cured” of his sexual orientation, Duberman dropped the therapy and came out in 1971, two years after the gay-rights movement began with the uprising at New York City’s Stonewall Inn, which he chronicled in 1993’s Stonewall: The Definitive Story of the LGBTQ Rights Uprising that Changed America.

A long-time professor of history at CUNY, Duberman is often called the godfather of LGBTQ studies, not only for launching CLAGS and for his early scholarship in the field but also for his activism as a founding member of the National Gay Task Force, the Gay Academic Union, and Lambda Legal. He has also written about labor and such diverse figures as the Beat poet and writer Jack Kerouac and the actor, singer, and activist Paul Robeson, and was briefly jailed for protesting the Vietnam War. His defense of abolitionists’ calls for radical change helped to shift historians’ view of the 19th-century antislavery movement in the US, and his 1963 play In White America was hailed as a driver of the civil rights movement’s Freedom Summer of 1964.

“His common thread has been to study people who dissent, who are outsiders,” says Robert Hampel, a historian of education and a professor emeritus at the University of Delaware. Duberman identifies with them. “It wasn’t always easy,” he says. “There was no queer history when I was in school. But academia was a relatively safe place to be gay.”

Though he didn’t come out until after his graduate experience, Duberman says it “speaks well of Harvard” that the institution was the first place he felt community as an adult. “I found my people there,” he says, “both academically and among my fellow grad students. It was a horrible time to be gay, and we would protect one another. I made lifelong connections at Harvard. I’m so glad my parents ended up seeing the light.”

Advancing the Study of Gender

As the only one of seven siblings to graduate from college, Myra Marx Ferree didn’t get much guidance from her family on an academic career. Luckily, she encountered mentors at every turn who were instrumental in helping her chart her path. The first was the director of financial aid at St. Peter’s College in Jersey City, where she worked during high school. He encouraged her to apply to other schools secure in the knowledge that she’d have a “free ride” at St. Peter’s. She ended up at Bryn Mawr, where she studied political science. Her advisor there suggested she apply to law school as a backup, but also that she apply to PhD programs to continue learning and “explore the greater world.” When she was accepted by both Harvard Law School and Harvard Griffin GSAS she enrolled at the latter to pursue her interest in social sciences.

At Harvard, Ferree found a new mentor in Thomas Pettigrew, PhD ’56, a social psychologist in the department who promoted a broad view of disciplines as complementary. “His primary focus was on race,” she says, “but he had put together a dataset that included questions on voting for a woman for president. He knew I was interested in what were then called sex roles, so he suggested I write about that.” Her article was accepted without revision in Public Opinion Quarterly, which cemented her confidence that she could not only learn but also contribute to scholarship at the highest level.

As her adviser, Pettigrew greenlighted Ferree’s dissertation topic on working-class feminists—not a popular theme at the time. “It just goes to show how much the study of gender in academia has advanced,” Ferree says. “We’ve gone from ‘that stuff is not interesting’ to the point where it has become institutionalized. I was fortunate that Tom took me seriously.”

Gender scholarship wasn't legitimate when [Myra] and I started writing about it. She helped lead the way for people to say, 'We need to look into this.'

—Christine Bose, Professor Emeritus of Sociology, State University of New York at Albany

Ferree went on to contribute extensively not only to the sociology of gender but also to interdisciplinary scholarship on family, social movements, political discourse, work and organizations, and the comparative study of feminism. And she honored her early guides in academia by becoming a legendary mentor herself.

“Myra really helped shape the field of sociology of gender by opening new areas of scholarship and bringing people into them,” says Christine Bose, a professor emeritus of sociology at the State University of New York at Albany. “Gender scholarship wasn’t legitimate when she and I started writing about it. She helped lead the way for people to say, ‘We need to look into this.’”

Not only was Ferree a key mentor for a generation of scholars, including Aili Tripp, the Vilas Research Professor of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where Ferree taught for many years, but “she also played a tremendous role in community building,” says Tripp, creating long-lasting scholarly platforms by serving on national committees, establishing awards, networking internationally, and holding editorial positions on a raft of journals. “Her real talent is collaboration.”

Ferree focused on intersectionality before the word was coined, trying time and again to show how gender, class, and race had to be understood together for social scientists to get any of them right. “I found it hard to limit myself by discipline or topic,” she says. “When I started out, every question was wide open. We feminists knew the old answers that assumed only men mattered were wrong, but lacked good research on women. It replicated stereotypes over and over again, and I wanted a fresh look at all of it. I never thought I’d be recognized for helping to transform social science research, but yes, that is what I was aiming for.”

Serendipity in Science

"It's about time," said Nancy Hopkins, PhD ’71, when told Joan Steitz had been nominated for the Centennial Medal. “She should have won it years ago.”

Hopkins, the Amgen Professor of Biology Emerita at MIT, was an undergraduate at Harvard when she first became aware of Steitz, then a graduate student. “I was kind of in awe of her,” Hopkins recalls. “At the time, people were asking, ‘Can women be great scientists?’ and it wasn’t long before Joan became one of the first to clearly show that, boy, could they ever.”

The work that so impressed Hopkins—and the rest of the scientific world—was on ribonucleic acid (RNA), which recently had a starring role in corralling the COVID-19 pandemic. Steitz’s many discoveries regarding the molecule helped to clarify how proteins form in the body and laid the groundwork for the development of targeted therapeutics, particularly for cancer, autoimmune conditions, and infectious and neurodegenerative diseases.

But she almost didn’t become a scientist. Now the Sterling Professor of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry at Yale and an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, she says she initially intended to go to Harvard Medical School (HMS) to be a physician. “I knew a couple of women doctors,” she says, “but I had never seen a woman professor of science or head of a lab and didn’t think it was conceivable.”

The summer before she was to start at HMS, she got a job in the University of Minnesota lab of the cell biologist Joseph Gall, who later went on to Yale and became known as a pioneer of cell biology. In Gall’s lab, Steitz worked on tetrahymena, a type of single-celled organism that has a nucleus enclosed within membranes. It was there that she decided bench science was her true calling.

I was kind of in awe of her. At the time, people were asking, 'Can women be great scientists?' And it wasn't long before Joan became one of the first to clearly show that, boy, could they ever.

— Nancy Hopkins, PhD ’71, Amgen Professor of Biology Emerita, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

It was her second turn at lab work; under the work-study program at Antioch College, Steitz had spent several terms working in the lab of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) biophysicist Alexander Rich, where she learned about the molecular building block deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and met James Watson, its co-discoverer. After doing her PhD work with Watson at Harvard, she got a postdoctoral fellowship in Cambridge, England, with his collaborator, Francis Crick, and the molecular biologist Sidney Brenner. “Crick suggested I find a project to do in the library,” Steitz says. “But I wanted to do bench work. So I went around and talked to the other postdoctoral fellows, and found out about an exciting but challenging project—to figure out whether special signals helped bind ribosomes to messenger RNA. None of the male fellows would take this on because they needed something to show when they went back to the US, but as a woman, I figured I’d never have a job like that anyway. And it turned into my whole life in science.”

“Joan predicted and proved how RNA-RNA interactions worked. These interactions play a crucial role in biological processes like protein production and gene regulation, so this set off the whole field,” says Yale biochemist Susan Baserga, a postdoctoral fellow in Steitz’s lab. “Her mind was always turning and thinking about the next big question. So her work really changed the world by showing how important RNA is to being human.”

Another way Steitz changed the world, Baserga points out, is by being an outspoken advocate for women in science. “She has tried to give the same opportunities she had to as many women as she could reach,” Baserga says.

It wasn’t only her mentees who took something away from those interactions. “It’s almost as much fun to share the joy of discovery with a younger colleague as to make the discovery yourself,” says Steitz. “I got very lucky that I ended up in this place and that place and meeting this person and doing that. Serendipity is very important in science. You have to keep your eyes open for opportunities.”

The Gold Standard for Scholarship

Arthur Wheelock's love affair with art started in his grandparents’ basement, where his mother’s women’s group met to paint. In third grade, he joined them and found that the creative act fed his soul and fired his imagination. But he never really considered a career in art until he was a young student at Williams College.

“My dad was the president of the family textile mill, the Stanley Woolen Company, in Uxbridge, Massachusetts,” Wheelock says. “I worked in the mill every summer and looked forward to it. But one Christmas when I was in college, my parents said ‘It’s wonderful that you like working in the mill, but you should not feel any obligation to it. You should follow your heart.’”

Follow his heart he did, majoring in painting and art history at Williams, attending Harvard Griffin GSAS, and studying old masters in the Netherlands, particularly their use of the camera obscura.

A 1973 fellowship brought him to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where his career would come to span more than four decades as curator of northern baroque and Dutch and Flemish painting, all while teaching art history at the University of Maryland.

There was a Rembrandt on offer and he described why he loved it in such a soulful, deep, moving way that I basically fell in love with Arthur right there.

—Thomas Kaplan, Businessman and Philanthropist

Among the many exhibitions Wheelock brought to the gallery, the most spectacular and influential was Johannes Vermeer, in 1995. It brought together 23 of the 35 works Vermeer was known to have painted.

“There had never before been a Vermeer retrospective,” says Earl Powell, who directed the gallery from 1992 to 2019. “It was an amazing achievement. It set Vermeer on a new trajectory and was a signal moment in the history of Dutch art.”

Wheelock is humble about such accolades, recalling instead events like the years he spent teaching about art at a boarding school in western Massachusetts. “I was so impressed by what these eighth graders could see with their untrained eyes,’ he says. “That experience became the basis for all the teaching I have done throughout my career.”

According to the businessman and philanthropist Thomas Kaplan, Wheelock has a special gift for imparting his vast knowledge of art and art history. “I met Arthur through a fellow collector at a dinner before a Sotheby’s auction in 2005 or 2006,” Kaplan says. “There was a Rembrandt on offer, and he described why he loved it in such a soulful, deep, moving way that I basically fell in love with Arthur right there.”

Wheelock worked with Kaplan and his wife, Daphne Recanati Kaplan, to create The Leiden Collection, one of the largest and most significant private collections of Dutch art in the world. “Arthur Wheelock is the gold standard in terms of scholarship regarding northern art,” says Kaplan. “He has changed the entire field of old masters. He is iconic within the space.”

“It’s true that I helped bring greater attention and understanding to a very important time in the world of art,” says Wheelock, “but what I feel most proud of in my career, as both a curator and a teacher, is that I helped transfer knowledge from one generation to another. I’ve been able to pass on the love of art, the emotional connection, and that has been very gratifying.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast