Moving Up

Raj Chetty wants to put the ‘mobility’ back in ‘social mobility’

Raj Chetty moved to opportunity.

When he was nine years old, his family migrated from India to the United States, where their educational and career prospects improved dramatically. His mother became one of the first women in his South Indian community to become a physician. His father became a different sort of doctor, earning his PhD from the University of Wisconsin- Madison and embarking on a career as an econometrician and statistician. His two sisters grew up to become professors at Emory University in Atlanta.

Chetty himself earned his PhD from GSAS in 2003 and is now the William A. Ackman Professor of Economics at Harvard, where he focuses on economic inequality and social mobility. He says that his passion for the study of these areas stems from the contrast he saw while still a child in the fate of his family and that of his relatives back in India. “It was very clear that my parents’ brothers and sisters didn’t have access to the kinds of opportunities my family did,” Chetty says. “One of them works in Singapore to help support his family in India and can’t be with his kids as they’re growing up. Another one had a very difficult manual labor job in New York City for many years and faced all the challenges that come with that type of work. It seemed to be largely through luck or choices their parents happened to make or even just where they grew up. And so I began to become quite interested in studying how you could expand opportunity more broadly.”

Today, Raj Chetty is at the forefront of a new generation of social scientists transforming the way we understand— and address—the problem of social immobility. After decades of analyzing massive data sets, Chetty says that the communities in which children grow up—the education they get, the social capital they inherit, and the relationships they form—have an enormous influence on whether or not they ascend the socioeconomic ladder during the rest of their lives. Neighborhoods matter, Chetty asserts, and in the years to come he hopes to make it possible for more families to change the trajectory of their children’s lives.

Growth is Not A Guarantee

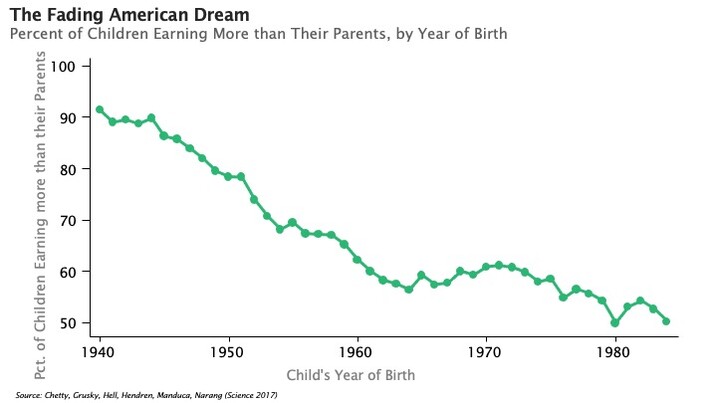

This is not your grandfather’s economy, particularly when it comes to socioeconomic mobility. According to Opportunity Insights, the Harvard nonprofit research and policy institute co-founded by Chetty, a child born in 1940 had about a 90 percent chance of earning more than their parents by age 35; only about 50 percent of children born in the early 1980s have surpassed their parents’ earnings.

In their search for the roots of social mobility, Chetty and his colleagues at Opportunity Insights analyzed US Census data on all children born in the United States in the early 1980s. The result of this work was the Opportunity Atlas, an interactive tool that enables the user to “trace the roots of today’s affluence and poverty back to the neighborhoods where people grew up.” In a 2020 research summary, “The Opportunity Atlas: Mapping the Childhood Roots of Social Mobility,” Chetty and co-authors John Friedman, Nathaniel Hendren, Maggie Jones, and Sonya Porter reported that “on average, moving within one’s metro area from a below-average to above-average neighborhood in terms of upward mobility would increase the lifetime earnings of a child growing up in a low-income family by $200,000.”

Danny Yagan, PhD ’12, associate professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, says that Chetty’s research has reshaped the way that scholars understand mobility and inequality.

“Before Raj’s work, we didn’t know how social mobility had changed over time,” he says. “We didn’t know how upward mobility varies by race and ethnicity.

Now we have systemic evidence on what correlates with upward mobility. The vast majority of Americans used to grow up to earn more than their parents; now it’s a coin flip, mostly because economic growth has become skewed toward top earners.”

Classical and neoclassical economists would say the solution to the problem of social immobility is to unleash the power of the free market. Keep taxes low. Get the government out of the business of picking winners and losers in the economy, and economic growth will improve everyone’s standard of living.

Chetty says that although markets allocate resources well and encourage innovation—for example, the astonishingly rapid development of a vaccine in the fight against COVID-19—economic growth alone is not a guarantee of social mobility. He points to the different outcomes for residents of two great American cities: Atlanta and Minneapolis. From 1990 to 2010, Atlanta had a higher rate of job growth than all but a handful of large metropolitan areas in the United States. Chetty and his colleagues analyzed census and tax data, however, and found that children who grew up in low- and middle-income families in Atlanta had low levels of income as adults. In fact, the city has one of the lowest rates of upward mobility in the country. Minneapolis, on the other hand, had relatively low job growth during the same period of time but some of the highest levels of income for adults who grew up there.

So what happened? How could an economy that produced so many jobs be a hub of social immobility? And how could an economy that produced relatively few be a bastion of opportunity for the people who live there? The answer, according to Chetty, is that cities like Atlanta import talent while cities like Minneapolis cultivate it.

“You might think, ‘We’ve just got to bring more good jobs to the city,’” he explains. “‘We’ve got to get the Amazon headquarters to our city and then things are going to be great.’ But in a capitalistic economy, everybody wants to hire the best talent they can. And if your institutions are not giving people the talent and the skills they need to get those jobs, a new company headquartered in Atlanta will simply hire people who grew up in other places. On the other hand, people who grow up in places with excellent schools and strong communities can prosper even if there’s unremarkable job growth. That’s why I think there’s not that much of a link between job growth and economic mobility.”

If growth alone doesn’t guarantee mobility, then what else could help move people up the ladder? Chetty says that place-based investments are critical to increasing opportunity in areas where it is currently low. Programs from education and job training to housing and health can have tremendous impacts on people’s long-run outcomes, and concerted investment at the community level is necessary for addressing the consequences of decades of disinvestment and other harmful policies. In addition, he says that it’s also important to consider the role of residential segregation and explore how we can help more low-income families access better neighborhoods today if they wish to do so.

Moving to Opportunity

Around two million families take part each year in the federal government’s $20 billion housing voucher program, the goal of which is to provide access to better housing and better neighborhoods to break the cycle of poverty. But after Chetty’s team created the Opportunity Atlas, they discovered a puzzling pattern.

“We laid the data on where families who received vouchers were living over the Opportunity Atlas data on where kids did well,” Chetty says. “Despite getting that assistance, these families were still living in low-opportunity neighborhoods where we saw through our historical analysis that kids were not likely to break out of poverty in the next generation.”

There are lots of good reasons why a family might not want to leave their community, even if it discourages social mobility—friends and relatives, for a start. But what if families did want to move but encountered barriers that discouraged them from doing so? What if they don’t have time to find a new apartment in an unfamiliar neighborhood? What if they’re confused and frustrated by the paperwork and process of connecting with a landlord that accepts housing vouchers? What if they just don’t have the money to move?

When we provided additional support to families—pointed out to them where the high-opportunity neighborhoods were in Seattle and gave them assistance to transition to these places—it dramatically shifted where they chose to move.

Chetty’s group wanted to see what would happen if some of the barriers to relocation were removed, so they partnered in 2018 with the Seattle and King County housing authorities to pilot a randomized intervention: Creating Moves to Opportunity (CMTO). Andria Lazaga, director of policy and strategic initiatives for the Seattle Housing Authority, says that in the lead-up to CMTO, her organization was unsure of how best to use its limited resources to enable families with vouchers to access neighborhoods they had traditionally been locked out of.

“Our efforts have largely been focused on improving the neighborhoods where families already live,” she says. “When Raj and his partners released their findings on the positive impacts for kids in families with low incomes of growing up in certain areas, we were excited to have guidance on where to focus. But we still didn’t know how best to break down barriers and support access to these neighborhoods or the extent to which families want to live there.”

During the pilot program, a thousand families came to the housing authority to apply for vouchers through the normal process. Half of them, however, got additional support including assistance with the housing search, connections to landlords, and a small amount of short-term financial assistance. “Think of it as removing some of the frictions that might make it hard to move to a higher opportunity place,” says Chetty. “We ended up finding that, when we provided additional support to families—pointed out to them where the high opportunity neighborhoods were in Seattle and gave them assistance to transition to these places—it dramatically shifted where they chose to move.”

In the control group, which didn’t receive the additional assistance, only 15 percent of families moved to high-opportunity areas. In the treatment group, however, the number jumped to 55 percent. “More than half ended up moving to places where we estimate as a result they will go on to earn about $200,000 more over their lifetimes,” says Chetty.

Lazaga says more than half the families who participated in CMTO indicate that they are happier since they moved. “We weren’t surprised to hear this since the navigators working with families centered their approach from a belief that they know what’s best for them; it’s the systems that get in their way,” she says.

Dr. Stefanie DeLuca, a sociologist at Johns Hopkins University, did early qualitative research with families to understand how CMTO worked. The data she gathered suggested that the reason the program was so successful in helping families move was not primarily the financial incentives or information about opportunity areas—it was the emotional support and communication strategies employed so effectively by program staff.

“They made families feel heard and included in the process of their moves,” DeLuca says. “They helped families feel optimistic and believe that they could succeed in moving to neighborhoods where they wanted to live and that were beneficial for their children’s futures.”

As a result of the Seattle pilot, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development has now allocated $70 million to replicate CMTO in nine other cities across the United States. The results of the program are so promising that, at a time of open hostility between Democrats and Republicans, Chetty says a bill to expand the housing voucher program by an additional $5 billion per year to provide the kind of support offered by CMTO has garnered bipartisan support.

“If I come along and tell you that you can take $20 billion,” he says, “and, by providing a little bit of additional support, you can make those dollars far more effective in achieving the goals of breaking the cycle of poverty, Republican or Democrat, that sounds like a good idea.”

Illustration By John Jay Cabuay

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast