Gauging the "Pygmalion Effect”

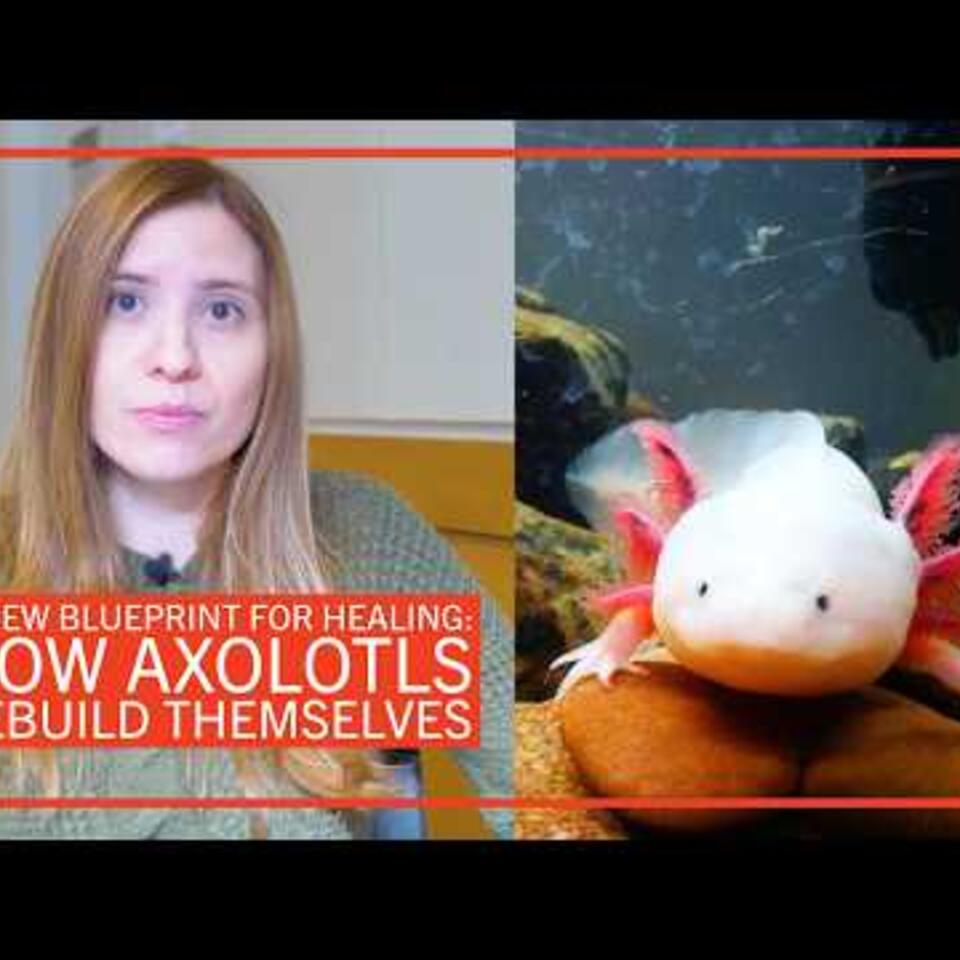

Nina Beguš explores the way that cultural tropes shape artificial intelligence—and reveal the creative limits of AI

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

He made, with marvelous art, an ivory statue,

As white as snow, and gave it greater beauty

Than any girl could have, and fell in love

With his own workmanship.

—Ovid, Metamorphoses

Alienated by the independence and power of the women in his community, a man creates an artificial mate and then falls in love with her. This ancient myth from Cyprus has persisted in different forms and genres through the centuries, from the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses in 8 CE, to George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play Pygmalion, to the 1990 hit film Pretty Woman. Today, Nina Beguš, PhD ’20, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Science, Technology, Medicine, and Society, sees the “Pygmalion myth” at the core of a technology that is rapidly changing the way humans live and work: artificial intelligence (AI).

“There’s the creation of the artificial human, the ideal woman,” Beguš explains. “There’s also this element of falling in love with her. That’s the trope. And I noticed with the first virtual assistants like Apple’s Siri that these were not just mere search. Because the search engine operated through speech, people tried to be more relational with them. It was very similar to what I saw in fiction.”

Beguš’s observations led her to conduct groundbreaking research on the way that human beings and artificial intelligence create. Using the Pygmalion myth as a prompt, she conducted an experiment that asked both human subjects and large language models (LLMs) to write stories. Her findings indicate that flesh and blood still has an edge over digital when it comes to imagination. They also suggest that the humanities, mostly left out of AI development, make crucial contributions to our understanding of machine learning and its cultural capabilities.

Both human writers and GPT easily followed the typical features of the prompt, demonstrating the pervasiveness of the Pygmalion myth in our cultural imaginary. But large language models, which had memorized voluminous works of fiction based on the story, generated narratives that were formulaic.

– Nina Beguš

Less Human than Human

With an eye on AI ethics, Beguš designed an experiment to gauge the societal biases and cultural specifics embedded in LLMs. She asked 250 people through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service and LLMs GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and Llama 3 to write a story based on a human who falls in love with an artificial human—essentially, the Pygmalion myth. Beguš chose crowdworkers—remote workers who perform small tasks— rather than professional writers because she was interested in the “averageness” of their narrative response.

When she analyzed the results, Beguš found that “both human writers and GPT easily followed the typical features of the prompt, demonstrating the pervasiveness of the Pygmalion myth in our cultural imaginary.” But large language models, which had memorized voluminous works of fiction based on the story, generated narratives that were formulaic. “They have an inner structure, and they follow it paragraph by paragraph,” Beguš says. “They were also bereft of local and cultural specificity. They wrote about utopian cities, but if you pushed them a little bit into ethnicity or culture, LLMs gave you a very stereotypical description. Generally, you got a single flavor of the prompt.”

Human participants, on the other hand, drew upon a vast reservoir of implicit cultural knowledge, crafting narratives rich with personal and collective experience. They also showed greater thematic variation and creativity. “Most stories [authored by humans] primarily dealt with romantic love and secondarily with its unconventionality,” Beguš wrote in her paper, “Experimental Narratives: A Comparison of Human Crowdsourced Storytelling and AI Storytelling.” “Following the cluster of motifs around the Pygmalion myth known from literature, only the human-authored stories additionally thematized loneliness, loss supplanted with doppelgangers, obsession with creating artificial life, serendipitous innovation, violence towards humans and towards humanoids, societal disapproval, and change.”

Beguš was perhaps most surprised to see how forward-thinking LLMs were in terms of gender and sexuality, an indication of the way that the models aligned with the values of their creators. “Newer language models became more progressive, not only in comparison to older models but also in comparison to humans in the experiment,” she says. “This is also where the innovation in story happened—at the level of friendship and polyamory.”

The takeaway for those building large language models is that, while current LLMs have a greater capacity for alignment and coherence, their creativity is limited. It’s instructive, Beguš says, that poets enjoyed earlier versions of GPT more than later ones. “They had way more fun with GPT-2.0 because it was not as aligned,” she says. “It was a little chaotic. It would assemble a string of words that you wouldn’t usually put together. You kind of want that element for creativity.”

Professor Mads Rosendahl Thomsen, director of the Center for Language Generation and AI at Aarhus University in Denmark says Beguš’s work takes scholars and scientists beyond speculation about the differences between the writing of machines and humans but produces and evaluates newly written stories. “Nina’s research has shown the strengths and weaknesses of what humans and machines can do,” he says. “Her background in comparative literature is essential in ensuring that quantitative studies are also put to the eye test.”

Bringing the Human to the Artificial

Beguš came to work at the intersection of the humanities and technology shortly after she enrolled at Harvard Griffin GSAS in 2014. Fascinated by the Pygmalion myth, she had decided to center her research on a Silk Road iteration of the trope. Around the same time, she noticed a modern version of the story in critically acclaimed movies, particularly Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), and Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014), where the companions were conjured not out of ivory but artificial intelligence.

“I was just astonished that this millennia-old narrative still had such a profound impact on our imaginative landscape,” Beguš says. “This was also the time when we were following all these breakthroughs in natural language processing and computer vision. I started wondering, why did they coincide so much? Why are technologists following these fictional scripts?”

There's the creation of the artificial human, the ideal woman. There’s also this element of falling in love with her. That’s the trope. And I noticed with the first virtual assistants like Apple’s Siri that these were not just mere search.

— Nina Beguš

The early 2010s were a time of breakthroughs in natural language processing. Virtual assistants like Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa had started to launch. Beguš noticed that all were voiced as women, harking back to the Pygmalion myth. She began talking to engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology working in affective computing—how to instill mimicry of emotions into machines—and found her observations struck a chord.

“They said, ‘We need your help with solving these issues,’” Beguš remembers. “And I realized they were asking the same questions while building these robots that I was asking in my research. It’s why I argue that humanistic knowledge and insights should be a part of the building process of these technologies.”

Beguš’s colleague Ted Underwood, a professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, says what’s distinctive about her work is that she’s “acutely aware” of the interaction between AI and human culture.

“When Nina studies language models as storytellers, she’s interested in how they remix narrative templates like the Pygmalion myth,” he explains. “In some ways, a language model’s treatment of Pygmalion is very formulaic, but in other ways, the stories created by models can innovate—for instance, by casting more characters as women than human writers typically do. On another level, she’s interested in the way fiction shapes our perception of AI—pushing us to imagine models, for instance, as things that either are autonomous agents, or ought to be and are falling short of that ideal. This bidirectional research agenda is still unusual, but I think Nina is blazing a path that many others will follow in years to come.”

Beyond Mimicry

Today, Beguš’s contribution extends beyond experimental research into the conceptual realm of a new field she calls “artificial humanities.” This interdisciplinary framework advocates for integrating humanistic inquiry—encompassing literature, history, and ethics—into the technology development process. “We cannot really understand and interpret AI without understanding and interpreting humans,” she says. “By applying these humanistic insights, technology can become more aligned with the nuanced needs of society.”

Beguš’s approach also translates into practical engagement. She has recently collaborated with tech giants and startups alike, providing a humanistic lens on technology development. “I was really surprised how welcome our contributions were in most circles,” she noted. Through these partnerships, Beguš hopes to shift the dynamics, aiming for a balance where humanities inform and critique technology, and vice versa.

Bernard Geoghegan, reader in the history and theory of digital media at King’s College, London, says that Beguš’s work goes beyond positioning the humanities in an age of STEM. “She excavates the messy and interwoven rapports among fields such as literature, engineering, computing, and theater, showing how they have always grappled with shared problems of modeling and molding artificial worlds. In so doing, Beguš positions humanistic research to respond to the challenges of a postindustrial society, where technics inflects nearly all aspects of human life.”

Looking forward, Beguš envisions a future where AI can break free from the constraints of human mimicry to explore new potentials beyond imitation. This involves leveraging AI not just as a tool but as a partner in creative and intellectual exploration. Referencing AlphaGo, a computer program developed by Google DeepMind in London that made unexpected and creative moves in the board game Go, Beguš asserts, “there was this novelty that the machine could provide. I think that’s the real value. It’s not the human mimicry. That’s kind of uninspiring.”

Beguš argues that understanding cultural imaginaries is critical in developing ethical AI. She observes that much of the technology’s development has been guided by cultural constructs embedded within stories and myths, often unconsciously. Her perspective encourages us to ask: What cultural values are embedded within our technologies, and how do they reflect or distort human experience?

“The paper has really proved thaty . . . people might not know what the Pygmalion myth is, but when I gave them a basic prompt, they were all able to follow it,” she says. “So, our interactions with AI are scaffolded by deeply entrenched cultural narratives which then show up in the technology. It’s kind of a bizarre situation. I think this is something I’m going to be researching for the rest of my life.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast