Doing As the Romans Did

Early Christians inherited— and reacted to—Roman view of sex and gender. How relevant are those ideas today?

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

Candidates in the 2024 US elections who identified as Christian often thundered against “gender ideology” claiming that God created two genders, male and female. Many Christian voters agreed, particularly self-identified evangelicals, showing their support for gender binaries at the ballot box. But Ben Dunning, PhD ’05, a historian of early Christianity, says the story of religion and gender is more complicated.

“Christianity is so often marshaled in contemporary political debates,” he says, “but often with very little knowledge of how incredibly rich and kaleidoscopic the Christian tradition is, especially when it comes to wrestling with sex and gender and desire as difficult questions, difficult parts of the project of being human.”

As Florence Corliss Lamont Professor of Divinity and Professor of New Testament and Early Christianity at Harvard Divinity School, Dunning studies sex and gender in texts from the first through the fourth centuries CE—formative years for Christianity as a new movement. He has found that, while gender complexity and instability are frequently mapped as a contemporary development and an import of the ideological left, the truth is far more interesting: early Christian texts saw sexuality and gender not as givens but rather as thorny questions to think through.

Sex as a Question Mark

Dunning’s work suggests that Christian notions of gender and sexuality are not fixed, stable truths that transcend time and place, but are rather dependent and contingent on the cultural norms of the society in which they are produced—and that they crop up again and again as open questions.

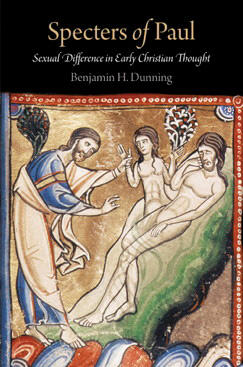

In his 2011 book, Specters of Paul: Sexual Difference in Early Christian Thought, Dunning explores a famous theological construct, put forward by the Apostle Paul. Writing to various early Christian communities, Paul offers them a new way of thinking about what it means to be human. He sets up a framework that spans from Adam as an emblem of creation to Jesus, the second Adam, as an emblem of the end of all things, with humankind poised in the middle.

“The question that emerges is, ‘What about Eve?’” remarks Dunning. “What about female bodies? What is their religious legibility in this space that is being determined by two paradigmatic bodies who are, on the one hand, set up as human universals, but on the other hand are male?”

A few generations later, in sermons, commentaries, and other religious texts, early Christian thinkers tried to solve the problem of how women fit into this theological picture in a variety of different ways: from framing female sexual difference as a temporary aberration that would be resolved at the end of time, to creating a parallel framework of paradigmatic female bodies that make reference not to Adam and Christ but rather to Eve and the Virgin Mary.

“But none of those solutions that the early Christians come up with fully work,” Dunning argues. “None of them fully solve the problem in a coherent, consistent way. They all, in one way or another, unravel on terms internal to their own arguments.” For example, around the turn of the third century, the Latin writer Tertullian of Carthage—anxious to preserve the superiority of the Adam-Christ paradigm over Eve-Mary—argues that Christ’s virginity is uniquely enduring by insisting, problematically, that Mary lost her virginity when she gave birth to Christ.

One of my goals is to show that complexity around sex and gender isn’t just a modern invention. It has deep roots and has been wrestled with for centuries in theological contexts.

– Ben Dunning

“I have become convinced that this unraveling is a kind of intellectual, political, and ethical resource, one that has a lot to teach us about what gender is in the first place,” says Dunning. “It’s pointing us to something fundamental about the limits of what we can know when it comes to desire and embodiment and sex and sexuality.” The unraveling also challenges the assumption that “man” and “woman” are straightforward historical constants—as Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, wrote on his website albertmohler.com, an unchanging sense of “God’s design in the biblical concept of manhood and womanhood.”

Karen King, Hollis Research Professor of Divinity, affirms that early Christian views of sex and gender were more unsettled than we might think. “In I Corinthians, for example, Paul implies that it is best to avoid marriage, while the writer of I Timothy condemns those who would abstain from marriage as being led by the devil,” King points out.

“One of my goals is to show that complexity around sex and gender isn’t just a modern invention,” Dunning says. “It has deep roots and has been wrestled with for centuries in theological contexts.”

Challenging the "Clobber Texts"

Dunning’s latest book project furthers his exploration of these tensions, focusing on theological arguments against homoeroticism from the first through the fourth centuries, before the fall of the Roman Empire. Many have argued that the Bible condemns homosexuality, typically by citing a specific set of Old and New Testament passages known colloquially as “clobber texts” because they have been used so commonly to assail the legitimacy of same-sex relationships. But Dunning’s new project asks how much relevance the concepts in these passages actually have to our contemporary understandings of homosexuality.

Perhaps the most prominent clobber text of all is Romans 1:1:26–27, in which the Apostle Paul references the “degrading passions” of women who “exchanged natural intercourse for unnatural” and men who “were consumed with passion for one another.”

Dunning notes, however, that this passage does not specifically denounce passion between two women; this reference to “unnatural” intercourse could allude to some types of sex between women and men. Moreover, during the Roman era in which Paul wrote this passage, questions around what today we would today call sexuality were far more concerned with issues of status and gender than they were with biological sex. “What they’re worried about is not whether it’s two men or two women,” Dunning explains, “but rather the status of each of the participants and who is doing what to whom.”

Indeed, an overriding concern with status rather than biological sex appears again and again in writings dating from the time of early Christianity. Examples are so numerous, Dunning explains, that it would be difficult to catalog them all. But he points to a few as representative: in Plutarch’s Roman Questions, a first-century explanation of Roman customs, the author suggests that freeborn Roman boys wear amulets because “it was not unseemly or shameful for the men of old to love male slaves who were in their season of youthful beauty . . . but they emphatically kept away from free boys, and free boys bore this sign so men would not be uncertain if they encountered boys naked.” Here the status of free boys is a matter of concern—not because they are male but because they will eventually be adult Roman citizens themselves; whereas enslaved men’s lack of social status—and lack of control over their own bodies—renders them indifferent, and thus appropriate, as objects of erotic desire, regardless of being male.

Similarly, the first-century philosopher Seneca invokes in his Dialogues the image of a strong man whose “sexual integrity is intact, [whose] manhood is safe, [whose] body is open to no shameful submissiveness.” In this context, what mattered most was not whether freeborn men were having intercourse with women, but rather whether they were the active, penetrative partner in a sexual encounter—because being the passive, receptive partner was associated with femininity and with lower social rank.

This historical context is essential background for understanding denunciations of same-sex erotic practice in the early Christian theological tradition. “Many of the arguments these theological treatises and sermons are making just don’t make any sense outside of a Roman ideological framework,” Dunning observes.

Roman views of femininity and its place in the social/sexual hierarchy carry into early Christian theology, which presents a major complication when these texts are evaluated in their original historical context: “While women could and did hold important positions of social influence in the Roman Empire, on an ideological level—at least in certain ways—ancient Roman culture is misogynist all the way down,” Dunning says. “It’s about devaluing women. What’s problematic for the Romans is that the penetrated or ‘passive’ partner is behaving like a woman. And that creates an interesting set of tensions when you fast forward into modernity and contemporary religious communities are inheriting this tradition and these texts. They are wrestling with them as authoritative in one way or another, and at the same time, they are seeking to affirm women’s full humanity. But one of my arguments is that you can’t actually extricate the condemnations of same-sex eros from the fundamental misogyny that animates those arguments.”

“The topic of desire is complicated,” observes King, whose own work traces the complexity of how early Christian texts frame women and gender. “Women are sometimes shown playing important roles—like Junia the apostle in the Letter to the Romans and Mary Magdalene in the Gospel of Mary—or they are silenced, as in I Timothy, which says: ‘A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet.’”

Interrogating any of the key terms in texts like the Book of Romans—“men,” “women,” “natural,” “unnatural,” “passion”— introduces problems and ambiguities, Dunning says, unsettling the foundation of any simplistic assertion that the New Testament has something definitive to say about homosexuality as we would understand and accept it today.

These diverse aspects of the early Christian tradition do, I think, show us that identity, when it comes to questions of embodiment and desire and sexual difference, is always going to be an incomplete project—and that there’s nothing wrong with that.

– Ben Dunning

“These texts don’t necessarily work to shore up identities, whether those are heteronormative ones or those of alternative genders and sexualities,” Dunning explains. “But whether we’re looking at gender-bending in martyr acts, or portrayals of Jesus as feminized, or complicated theological treatises that both value and devalue erotic desire simultaneously, these diverse aspects of the early Christian tradition do, I think, show us that identity, when it comes to questions of embodiment and desire and sexual difference, is always going to be an incomplete project— and that there’s nothing wrong with that. They show us that it’s actually a beautiful space of possibility, not a problem we have to fix.”

Through this work, Dunning is tracing the complex ways that early Christian thinking moves through history and becomes part of our cultural inheritance in the present. He also underscores a powerful broader lesson that the tensions in these ancient texts can teach us. As Dunning puts it, “The right to claim truth about someone else’s embodiment and desire isn’t one we ever truly have.”

Ancient Studies, New Connections

Dunning joined the Harvard Divinity School (HDS) faculty in 2022 after 16 years as a professor at Fordham University. It was a homecoming of sorts. Dunning not only earned his PhD in the study of religion from Harvard but also was a 2009–2010 Women’s Studies in Religion Program (WSRP) research associate (RA) at the Divinity School—the first male RA in the program’s 35-year history.

During his time at WSRP, Dunning worked on what became Specters of Paul. The work is the product of his distinctive and varied research expertise: the history of gender, sexuality, and religion, particularly in early Christianity and the New Testament, as well as critical and feminist theory, queer theory, and hermeneutics.

Dunning says the modern academy has not always been organized to support such diverse research interests—but the landscape is changing.

“Things were more siloed when I was a graduate student,” he recalls. “There was religion, there was the classics, there was history. One thing that’s very exciting about the community at Harvard is there’s a lot of intellectual engagement and cross-fertilization.”

Today, Dunning teaches courses offered jointly at HDS and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS). “Sex, Gender, and Sexuality” explores the work of 20th-century thinkers from psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan to the philosophers Michel Foucault and Judith Butler. “Histories, Bodies, Differences,” co-taught with HDS Professor Amy Hollywood, brings contemporary life and critical theory into conversation with premodern texts and history. In Dunning’s view, these courses open crucial intellectual doors for his students.

“I work with so many students, both at the Divinity School and in the FAS, who have complicated relationships to Christianity, to Judaism, to gender and sexuality, and are trying to make sense of that,” Dunning says. “Many of my students have found that when it comes to questions of gender, sexuality, and religion, straightforward or facile answers—whether progressive or traditional—have not worked for them. So they want to get into the weeds. They want to work through these questions in their historical and religious dimensions, in their full complexity. I try to create ways that give them that space.”

Looking ahead, Dunning hopes his work will enable his students and the public to better understand the complexity of sexuality and gender, and how Christians—both then and now—have rejected simplistic formulations of either.

“To assume that sex and gender are self-evident, and that that has been the position of the New Testament and the Christian tradition monolithically and with a single voice forever, is actually to step away from the tradition,” Dunning says. “Through my work, I’m trying to do justice to a tradition that has always been a little bit confounded by issues of what it means to be a body and what it means to desire. These are questions worth wrestling with.

Banner photo by Mark Ostow

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast