Complex Recipe

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

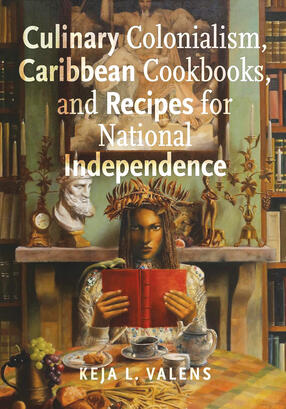

The history of the Caribbean over the last 500 years is often portrayed as one of colonization versus liberation. In her new book, Culinary Colonialism, Caribbean Cookbooks, and Recipes of National Independence, Salem State University Professor Keja Valens, PhD ’04, looks at the region and its people through a more complex lens. By exploring the food and food practices of the Caribbean, Valens lays bare both the atrocities of settler colonialism and the multiple inheritances that frustrate a neat moral ordering of the region’s culture.

How do Caribbean cookbooks transcend cooking instructions to become a “vast, varied, and a vital mode” of expression?

From the 19th century to the mid-20th century, most of the cooking in Caribbean countries was done by people who learned through oral and practical transmission and were often illiterate. Even in the 20th century, when literacy expanded, many who owned cookbooks also would employ cooks. Few people who read the books cooked from them. Then, even if you did read the books and tried to follow the recipes, you might not end up with anything edible because their function was really to convey ideas about how to make a dish that were already known to the people preparing it. So, what these cookbooks really did was represent their countries and cultures as distinct and independent rather than as colonies. If you called your recipe Jamaican, you were saying there was such a thing as Jamaican cookery.

For instance, there’s one early 20th-century cookbook written by a Frenchwoman about the French Antilles. In it, she claims bananas originated in France. So, when another cookbook comes along and says, “Bananas and plantains came to the Caribbean with African slaves,” the writers are saying, “This culture comes not only from Indigenous people, not only from European colonizers, but also from Africa, and our culinary traditions are a product of that mixture.”

Your book discusses the tropes of scarcity and danger, abundance and edibleness in the first writing about Caribbean food and food practices. How do they emerge?

Christopher Columbus and Diego Álvarez Chanca, the doctor who accompanied him on his second voyage to the Caribbean, both wrote chronicles and letters. They knew the principle of terra nullius: if you arrived somewhere and there was no culture, then it was blank ground and you could claim it for your country. For instance, they wrote home about having found pots full of human bones. Now, there is no evidence to suggest that Indigenous people in the Caribbean were practicing cannibalism. They were eating animals—including large, big-boned sea animals. But among the first things Columbus and Chanca wrote was basically, “There’s no culture here and the people are cannibals.” That’s the danger trope. They didn’t recognize the farming or cooking practices of the indigenous people except as savage.

One example of the scarcity trope had to do with bread. For the Spanish and other Europeans, bread was food. So, when they didn’t find any in the Caribbean islands, they wrote home that there was no food there. Columbus and Chanca’s correspondence was used by other Europeans who wrote histories of the New World but never went there. They just repeated what the letters said. So, there was a lot of power in those few chronicles that came back across the ocean.

As much as Columbus and Chanca needed to find no culture or civilization with a claim to the land, they also needed to find valuable things to expropriate and send back to the Queen of Spain so she would keep funding their voyages. The Caribbean is a tropical zone. There are a lot of fruits and vegetables that grow there. In the 1500s the soil quality was much better than it is now because it hadn’t been destroyed by plantation agriculture. So they wrote back that the Caribbean was the Garden of Eden. That’s part of the edibleness trope, as if all these foods were given by God rather than cultivated by humans. It went along with the idea that “We’re the men meant to come here and impregnate, eat, take up, consume, and then render civilized this natural bounty.”

Finally, what is the process of “creolization” you say guides your analysis of Caribbean cookbooks? How does it frustrate attempts at a “neat moral ordering” of the region’s culture?

Creole originally meant being born in a place. Up through the 19th century, the term was used to talk about people who were of single ancestry but born in the Caribbean. By the 19th century, though, a lot of folks who were born in the Caribbean had multiple ancestries, as did the plants and animals. And so Creole took on a new meaning.

That creolization is reflected in food and food practices. The Spaniards brought pigs that decimated the yuca and cassava, staple foods for the indigenous people. But over the years, pigs were indigenized and became part of the regional diet themselves. Today, empanadas or patties, which often use pig fat and pork as well as white flour, are considered a classic Caribbean dish.

Now, many Caribbean people thinking about food today are concerned about nutritional issues with all that white flour and pig fat. So just to say, “This is Creole food. It belongs to us,” doesn’t erase the problematic legacy of bringing unhealthy things to the Caribbean and forcing people to eat them. But it does allow for thinking about this complicated process of coming together in ways that are lovely as well as fraught. After all, who doesn’t enjoy a good empanada?

Cover photo by Tony Rinaldo

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast