Colloquy Podcast: A Short History of Technology and Thought

Every technology is accompanied by a cultural technique, says artist and media scholar Emilio Vavarella, a PhD candidate in film and visual studies and critical media practice at the Harvard Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “You have the calculator, but you also have the number,” he says. “Everything we do, from speaking to being able to write an imaginary story—all of these are specific techniques that we have developed. It’s what makes us human.” Vavarella calls these frameworks media models—abstract models that mirror specific technologies. Media models are the paradigms through which humans try to understand the world and themselves. Their development is slow and not necessarily linear or progressive, but it embraces all sectors of human life. In this episode of the Colloquy podcast, Vavarella gives a short history—from pre-historic hydrology to modern computation—of the ways in which technology and culture have interacted to shape the ways human beings think.

(This talk was originally given during the Harvard Horizons Symposium in 2023. The transcript below has been lightly edited for clarity and correctness.)

My work begins by creating a space of interdisciplinary research. My work is not bound to a particular material or discipline. It moves between different forms of art and theoretical experimentation. My goal is to investigate our relationship with technology, but for way too long, technology and culture have been seen as opposites. My work begins with the refusal of this binary division. On the one hand, I refuse technodeterminism, which roughly is the idea that technology determines cultural values. But I also refuse a reductive view of technology as the mere product of culture. I find that the reality is more complex, and it’s full of interactions between ideas, between materials and concepts, between different disciplines. And it is by paying attention to these complex connections that we can begin to understand how technology and culture constantly influence one another.

My doctoral research began six years ago. I was studying the beginning of perspectival drawing during the Renaissance, and I was struck by learning that the same rules used by painters and architects to represent space were also used to understand the functions of the human eye. So I ask myself: is this just a rare historical occurrence, or are there other moments in history when specific techniques or technologies shaped a certain understanding of human faculties?

To find out, I had to push my gaze as far back in history as I was able to, and my journey begins by looking at ancient clay artifacts in connections to some of the earliest myths, stories, and incantations that have survived to our days. I was particularly fascinated by myths to which a supernatural being molded the first humans out of clay. Now, these myths attempted to answer the age-old question of where do we come from, but they also corresponded to a specific set of technologies, like pottery wheels and pottery ovens, and a specific set of techniques, like sculpting, molding, and baking clay. So, the technical knowledge of producing clay artifacts was shaping a story about the possible origin of human beings.

I coined the term media model to describe the process we are now familiar with—the extraction of an abstract model out of a specific technique or technology and the use of that model in different contexts. Every time we talk about the eye as a lens, or the heart as a pump, or our brain as a computer, we are not simply using metaphors. We are talking about how techniques and technologies shape our understanding of ourselves.

My next example brings us to some of the earliest techniques for irrigation, and my research suggests that all of our concepts and ideas are always grounded in specific techniques. So in conjunction with the development of techniques to irrigate the fields and deviate the course of water streams, the human body is reconceptualized as a complex system of circulation. A healthy body was a body in which fluids were flowing well. Illness, on the contrary, could be caused by a blockage in this flow or by a wound, causing a spillage of precious bodily fluids. Now, this hydraulic model persisted for centuries, and something important to keep in mind is that media models don’t simply succeed one another. They often coexist, even though some of them may reach a hegemonic state and may converge.

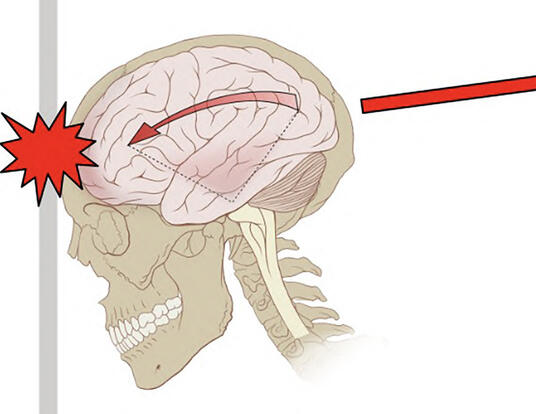

So, let’s jump to the 17th century. I’ll show you how this can happen. This is a moment marked by the development of new mechanical technologies, like pendulum clocks and pocket watches. And at first, hydraulics plays a major role in this mechanization, but the emphasis starts to shift from how to make things flow better to using hydraulics to better mechanize things. And my research shows that, in conjunction with this process of mechanization, the human body is really conceptualized, once again, this time as an automaton, a complex system of cogs, pivots, body parts that respond mechanically to the displacement of weights.

My research shows how media models are one of the most effective ways we have developed to produce answers, but they also shape the questions that at any given time can be posed. We could say that each media model corresponds to a certain horizon of meaning, a set of possible thoughts that can be formulated and expressed. Each media model is limited in its own specific way, and this means that a history of media models is not a history of progress. Hydraulic models fail to take into account the more mechanical aspects of reality, and mechanical models ignore the more fluid aspects of reality. Computational models tend to ignore aspects of reality that cannot be easily quantified.

Looking back, I started this journey six years ago, thinking about the ways in which perspectival drawing was informing human vision, and what I found is that beyond human vision, the very way we see ourselves and our world has always been influenced by the techniques and technologies available to us. So, as we navigate a world increasingly dominated by computational technologies, I believe it is more important than ever to pay attention to how every technology shapes our sense of reality.

Thank you.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast