Back from Nowhere

How Latin American writers and artists took up the cause of refugees

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

From the fugitive man

I have only the footprint,

the weight of his body

and the wind that blows him.

No address no name,

not the country not the village,

only the damp shell

of his footprint,

only this syllable

by the sand collected

and the Earth—Veronica

who to me babbles him!

-Gabriela Mistral, “La Huella” (“The Footprint”)

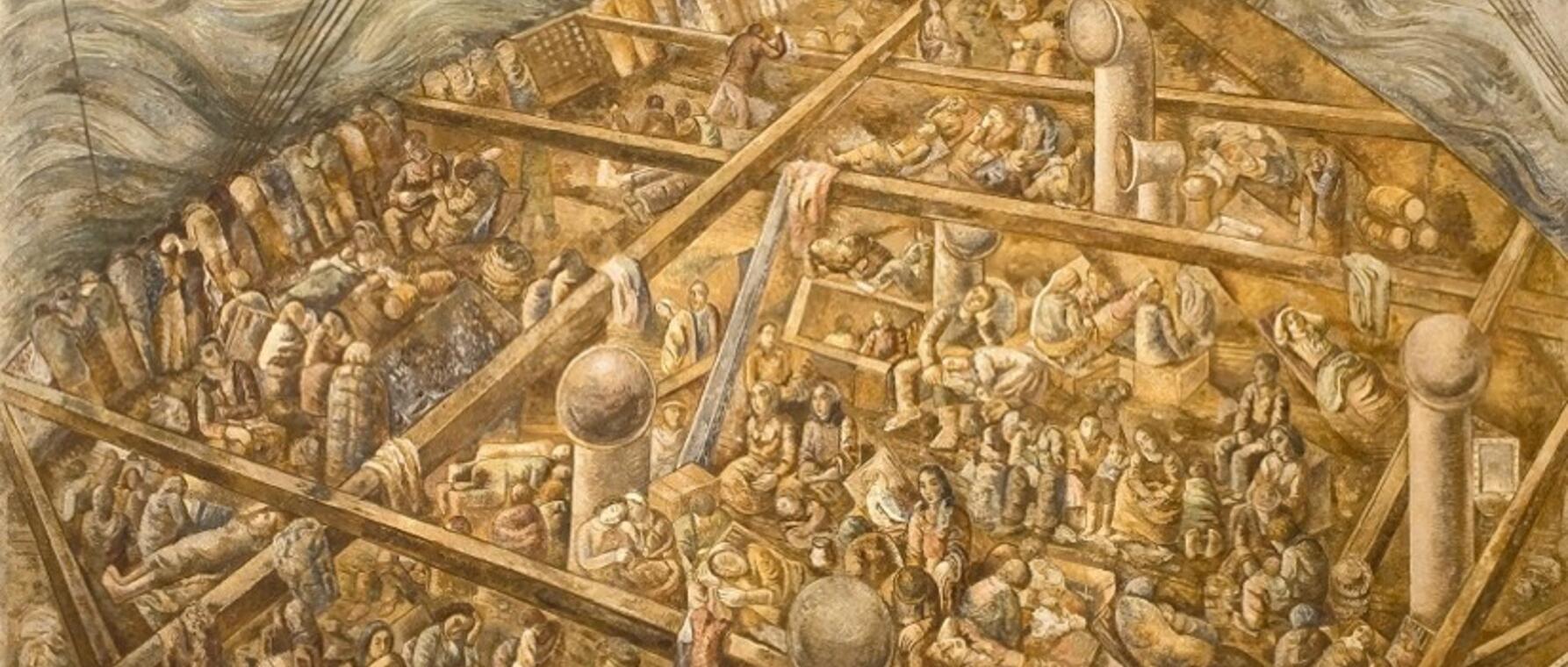

Like the poetry of his fellow Latin Americans, Mauro Lazarovich’s 2024 Harvard Horizons project is not only humanist but also humanitarian.

“I wanted to make a contribution to the humanities by saying that literature and art have something to bring to the table when we are talking about refugees,” he says. “And not only literature in general but specifically Latin American literature.”

With “Citizens of Nowhere: Stateless and Refugee Literature in Latin America,” the graduating Harvard Griffin GSAS PhD student in romance languages and literature shines a light on the experience of the stateless—and the writers and artists who brought those “erased” by governments and bureaucracies back into view through their creative work.

From Citizen of the World to Exile

The title of Lazarovich’s project is taken from the words of the writer who inspired it. Stefan Zweig was an Austrian Jew stripped of his citizenship and passport in the lead-up to Nazi occupation in the 1930s. In his memoir, The World of Yesterday, Zweig, one of the most internationally popular writers of the early twentieth century, chronicled his journey from cosmopolitan to exile in Brazil.

“Zweig thought of himself as a citizen of the whole planet, crossing boundaries and borders without a passport and visas, just like sliding across an ice rink,” Lazarovich says. “Then he lost his citizenship and was forced into exile and became a refugee. He wrote ‘My literary work . . . has been burnt to ashes in the country where my books made millions of readers their friends. So I belong nowhere now, I am a stranger or at the most a guest everywhere . . . . Against my will, I have witnessed the most terrible defeat of reason and the most savage triumph of brutality in the chronicles of time.’”

Lazarovich’s intellectual Virgil on this journey is the historian, philosopher, and political theorist Hannah Arendt. In her 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt observed that having lost the rights of citizenship in their native countries, refugees had only natural and human rights. Enlightenment thinkers asserted that these rights were “inalienable” but in fact, they placed the stateless person in a position of radical vulnerability.

“I think that's what happened to Zweig,” Lazarovich says. “His cosmopolitanism provided him with this very emancipatory discourse but once he lost his national rights, he discovered that the discourse provided no protection to him, that he was alone, and that it was a struggle to get anyone to recognize his rights as a member of the human race.”

My literary work . . . has been burnt to ashes in the country where my books made millions of readers their friends. So I belong nowhere now, I am a stranger or at the most a guest everywhere . . . . Against my will, I have witnessed the most terrible defeat of reason and the most savage triumph of brutality in the chronicles of time.

—Stefan Zweig

Speaking of the Rightless, Envisioning New Rights

For the creatives Lazarovich studies, the same experience that moved them to make the stateless a subject of their art also inspired them to become public intellectuals advocating for new rights of asylum for refugees. Some, like the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral—who in 1945 became the first Latin American to win the Nobel Prize for literature—did so as formal representatives of their nation’s government.

“In 1938, Mistral was a consul for the Chilean government in the French city of Nice,” Lazarovich says. “As concerns grew about a war with Germany, French Jews increasingly showed up at the refugee office next door to the consulate, attempting to flee Europe in advance of a Nazi invasion. She described their desperation to leave as a kind of ‘fugue neurosis.’”

In 1939, Mistral’s poem, “La Huella” (“The Footprint”), was published in the Buenos Aires literary magazine, Sur. While the work has been interpreted as an allegory of Jesus Christ fleeing a hostile humanity, Lazarovich interpreted the manuscript versions of the poem as well as an unpublished version and Mistral’s correspondence about the work and came to a different conclusion. “It’s about a refugee,” he says. “It's Mistral working through the encounters she had in Nice."

Those encounters had a transformational effect on the author, Lazarovich says, compelling her to become a public intellectual and to work with the United Nations to secure postwar cosmopolitan rights. The imagination that had inspired her poetry began to move into the diplomatic world as she conceived new transnational human rights for refugees.

“She wrote about the concept of genocide and the Genocide Convention,” Lazarovich says. “She gave speeches about the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. She talked about new rights of asylum. So, in many ways, she embodies the two claims I make about writers and artists—namely, that literature and art both captured the concept of rightlessness and envisioned the rights of asylum.”

To Bring a New Reality into Being

Lazarovich learned to love literature as a child growing up in Salta, a small town in northern Argentina close to the borders of Bolivia, Paraguay, and Chile. His passion for transnational rights and politics may have its roots in the Model United Nations simulations in which he participated as a high school student. “It was my first encounter with the ideas behind global citizenship and human rights.”

As an undergraduate in Buenos Aires, Lazarovich studied first history and then Latin American literature before landing at Harvard Griffin GSAS for his PhD in romance languages and literature. During his first term at the University, Lazarovich despaired of democracy’s decline around the world—and the potential for authoritarian leaders to exacerbate species-level threats like war and climate change—so he “took a lot of courses about the end of the world.” Studying the global refugee crisis, he read Zweig’s The World of Yesterday. “That encounter with Zweig was the seed that triggered my PhD research," he says.

Professor Diana Sorenson, one of Lazarovich’s faculty advisors, says that his research illuminates scholars’ understanding of Latin American and world culture, replotting the back-and-forth of influences of migrants, their arrivals, and their insertion in new nations and cultures.

“The very displacement that inheres in statelessness is shown by Mauro to transform the realms of visual and verbal arts,” she says. “Moreover, by dealing with canonical writers such as Gabriela Mistral and Pablo Neruda in their capacities as writers and as diplomats, he shows the complex and productive interactions between the humanities and the public sphere. After Mauro, we will read these great writers differently, with a sense of their power to interpellate leaders and citizens, as they try to shape the world with the authority of their artistic voice.”

After Mauro, we will read these great writers differently, with a sense of their power to interpellate leaders and citizens, as they try to shape the world with the authority of their artistic voice.

—Professor Diana Sorenson

Like the artists and writers he studies, Lazarovich hopes that his work can be relevant for people inside and outside of the humanities—and the academy. That’s one reason why he’s volunteered for the past two years at Harvard Law School’s Immigration and Refugee Advocacy Clinic as an interpreter for Spanish-speaking asylum seekers. His goal is to enable thinkers from different professions and fields of knowledge to better understand statelessness—and to present the issue as a genuinely global problem across national, linguistic, and disciplinary borders.

“In a way, both the poet and the lawyer are trying to do the same thing: to bring a new reality into being through their words,” he says. “By exploring this meeting point, we find what's poetic in the law and what’s legal in lyrics. That's my way of trying to write something compelling and interesting for lawyers, activists, politicians, and artists concerned with the refugee problem. Hopefully, I'll keep finding ways to be in conversation with all of them.”

Learn more about the 2024 Harvard Horizons Scholars and see them on stage at the campus-wide Harvard Horizons Symposium in Sanders Theatre on April 9.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast