Your Brain on Nature

Wendy Weiger, PhD ’97

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

As a PhD student and then a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard, Wendy Weiger studied the electrical and chemical workings of the brain and developed an evidence-based framework for physicians to integrate alternative therapies into conventional medical care. She discusses the personal tragedy that inspired her to leave academia, the healing power of nature, and her shift to environmental advocacy and writing.

Learning to Love Nature—and Fear for It

When I was an undergraduate at Harvard, my father committed suicide. In learning to deal emotionally with the aftermath of what happened, I found that spending time in nature was very therapeutic for me. There is a growing body of scientific evidence that time in nature is beneficial for our emotional well-being, our cognitive function, and even our longevity. This makes sense, as for most of human history, we lived in nature 24/7 as hunters and foragers, and that's how our nervous systems evolved—to interact with the natural world.

This was also the time when I became more aware of how threatened the natural environment is. We are heading toward a mass extinction, the first one in sixty-five million years, caused entirely by humans. We may lose more than half of the species on Earth. E.O. Wilson, who taught my freshman biology class at Harvard, raised the alarm for this over 30 years ago, but the situation has only gotten worse. We haven't addressed it in any meaningful way. We like to think that our technology can solve everything, but we rely on what are called ecosystem services for the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat. We are not independent from nature. If we lose half of the species on Earth, human life on Earth will be significantly undermined.

We're approaching several tipping points: the loss of the Amazon rainforest, the melting of large ice sheets, and the shutting down of ocean circulation that controls the climate in Europe. If these events happen, civilization will not be what we've known it to be for the last ten thousand years.

Nature Writing in Maine

I moved to northern Maine at the end of 2003. My idea was to write about the human relationship with nature and help people connect with it emotionally to bring about real change. I have a longer book manuscript for which I'm currently seeking a publisher, and I've also published articles and a shorter book through a small nonprofit that I founded. Through the nonprofit, I offer programs intended to guide people into deeper connections with nature. I offer mindful hikes and multimedia presentations that can be adapted to a variety of needs and interests.

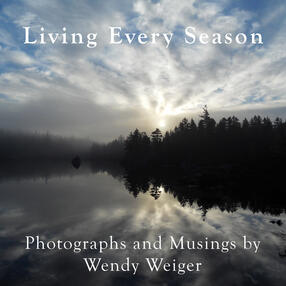

The shorter book that I published is called Living Every Season: A Mindful Year in the Maine Woods. The title draws from Thoreau, who said, "Live in each season as it passes; breathe the air, drink the drink, taste the fruit, and resign yourself to the influences of each." I take people through the four seasons of the Maine woods using photographs. In my text, I interweave science, spirituality, and aesthetics in a way that I hope will draw viewers into the images and help them connect more deeply.

What I really wanted to convey was a sense of wonder. I think many adults have lost that childlike sense of wonder, which can be a powerful motivator. When we look at the complexity of the natural world around us and pause to think about it, we're surrounded by what could be considered miracles. With every breath we take, we are breathing in oxygen and breathing out carbon dioxide, and the carbon dioxide we exhale is taken in by the trees, which then make more oxygen for us to breathe. With every breath, we're in this reciprocal connection with the life around us. If you pause to think about it, even on a very basic level, it's amazing. To motivate people, we need to rekindle that sense of joy and wonder.

In the longer book manuscript, I delve more into science and spirituality. The book is called Heaven Beneath Our Feet. That title also comes from Thoreau, who said, "Heaven is under our feet as well as over our heads," in Walden. In it, I explore how we lost our connection with nature, how we can regain it, and the joy it will bring us. This joy can motivate us to take better care of the Earth. I offer concrete guidelines for what people can do in their own lives, wherever they live. You don't have to be out in the wilderness; in cities, we're still surrounded by nature. Those basic reciprocal interactions are going on every second of our lives. Wherever you are, you can connect more deeply with nature. You can gain immediate rewards from that in terms of your well-being. It can give you the energy to make changes or advocate for changes that will improve the health of all life on Earth.

She’ll Have the Lobster

During my PhD years, I worked in the lab of Professor Ed Kravitz, studying the modulation of behavior in lobsters by serotonin, a neurotransmitter used in almost all phyla with nervous systems, from jellyfish to humans. I was ultimately interested in how the human brain worked, but when considering which lab to join, Ed persuaded me that I would do well to select a simpler model nervous system where I could work out specific circuits that affected behavior. I decided to focus with Ed on the serotonergic modulation of behavior in lobsters, hoping it would help us understand some of the fundamental building blocks of the circuitry and chemistry that control behavior in us.

The piece of research that I felt truly represented my best work was a paper in which I reviewed the research of many people who had gone before me. I looked at the role serotonin played in behavior across animal phyla, starting with worms and continuing through invertebrates like lobsters up to humans. I felt my heart lay in that kind of synthetic research, drawing connections between the work many other researchers had done and bringing it together into a greater whole. Although the lab work was essential for me to understand what goes into basic research, I was moving toward more synthetic research and writing. One of the messages I took from it is how interconnected our species is with all life on Earth.

I'm grateful to Ed and David Eisenberg, my postdoctoral mentor at the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine, for providing the infrastructure, support, and encouragement that allowed me to delve deeply into questions that mattered to me and other researchers and clinicians. It's so important to offer that supportive environment for students and postdocs. Looking back, it was a privilege to spend years delving into questions that have real meaning rather than just going through the mundane tasks of daily life. I’m thankful that Harvard provided the infrastructure and that my advisors gave me the opportunity to explore these questions.

Cover photo by Noah Lang

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast