The Value of School

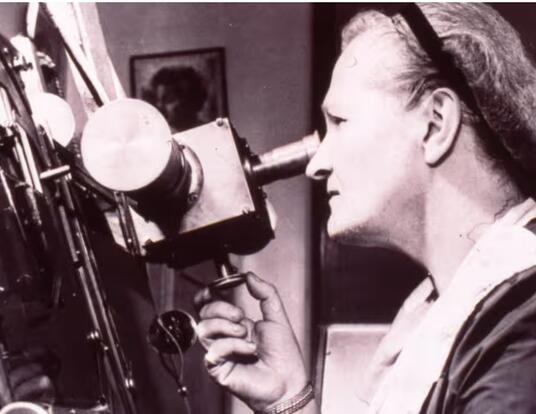

GSAS Voices: David Deming, PhD ’10

Throughout its 150th anniversary year, GSAS is foregrounding the voices of some of its most remarkable alumni and students as they speak about their work, its impact, and their experiences at the School.

David Deming serves as the Isabelle and Scott Black Professor of Political Economy at the Harvard Kennedy School where he is also academic dean. He discusses why labor markets reward educational attainment, his study on the growing importance of “soft skills” in the workplace, and how his time at GSAS taught him to love the creative process of research.

Evaluating Education

My research is focused on labor markets and education. The question that has animated me for a long time is, "Why do we see such large and persistent economic returns to education?"

There are thousands of studies on this subject, and almost all find that education pays off, to the tune of about a 10 percent increase in annual earnings per year in school. What is amazing is that this result holds for different levels of education—pre-primary, primary, secondary, and undergraduate—and also in different settings, including more and less economically developed countries.

Yet we don’t really know why. I was kind of obsessed with this puzzle during my time at GSAS, and I still am, because it seems so important, and yet none of the answers are fully convincing. I have spent my entire career trying to find out “why” education pays.

I think a big part of it is “soft skills.” You’ll hear people say all the time that they majored in psychology and learned nothing in the classroom that was then beneficial in the workplace. I think that’s wrong. Education is a transformational experience, and it’s hard for us to go back in time and imagine ourselves taking a different path. I believe education changes our ability to think critically and process information. We don’t have good terminology for these kinds of things; we call them soft skills because we don’t understand them very well. In my research, I try to make soft skills “harder” by being conceptually precise about concepts like teamwork and problem-solving and then developing and testing measures of such skills in the lab and in the field.

The Rise of “Soft Skills”

I first started working on soft skills while I was an assistant professor at Harvard. I was interested in the growing importance of teamwork and social interaction in the labor market. Outside of the ivory tower, everyone knows that the ability to have a good conversation and understand where you fit in a team is crucial. Yet economists always focus on individual behavior and rarely study teamwork. Yet working in a team requires us to understand a fundamental economic principle—comparative advantage. For example, what is the right division of labor when I write an article with one of my graduate students? They probably do the data work, and I focus on the bigger picture framing. That’s a different division of labor than if I were writing an article with my graduate school advisor. Do I know how to fit into a team production process? Do I always make teams better regardless of where I fit in? Teamwork is essential to economic activity, but economists weren’t studying it at all.

I was on my junior sabbatical, which allowed me to spend three months working on this and nothing else. It was different than the other work I had done. I created a crude measure of social skills, like how friendly you are, how extroverted you are, applied it to survey data, and showed that the labor marketing return to those skills increased over time. Jobs requiring social interaction became much more important in the domestic labor market. They had grown as a share of all jobs by more than 10 percentage points between 1980 and 2012, and they were paying higher wages. Basically, if you wanted a high-paying job, you needed to be good at both analytical thinking and problem-solving, and good at teamwork. The days of crunching numbers without talking to others were over.

That ended up being my most cited and most influential paper. It got me tenure here at Harvard, and it’s my best-known scholarly work.

Discovering Creative Research

When I was a student at GSAS, I formed a tight-knit study group with several of my peers. We had to read hundreds of papers as part of our training, so we split the papers amongst ourselves based on interest and wrote short summaries for each other. Then we would get together and discuss them. This was an incredibly important experience for all of us, I think. Summarizing and describing those papers for my peers deepened my knowledge of the field so much. Without that, classes would have been really difficult—and a lot less fun!

Research is a creative enterprise. And that is my favorite part of the job. My students ask me, "What’s the secret to success in academia?" There is no secret. You have lots of ideas, and every once in a while one of them is a good idea. And then you have to execute on it, which takes lots of time and effort. The execution can be a slog, so you have to really love creating and communicating ideas to make the other stuff worth it. If you love it, it doesn’t feel like work. If there’s a secret, that’s it. And I never would have discovered that if it wasn’t for the fun I had with my peers at GSAS.

Photo courtesy of David Deming

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast