Suspicious Minds

The impact of violence on kids’ ability to trust—and thrive

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

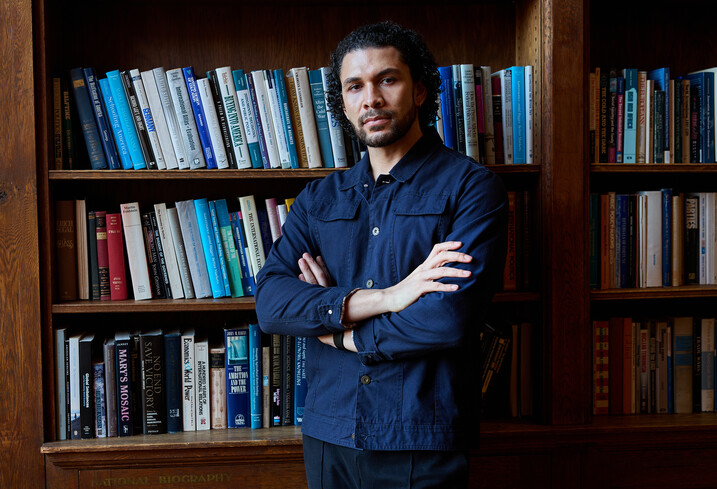

Growing up in Ferguson, Missouri, Steven Kasparek witnessed violence. He experienced it himself. He was left with some burning questions about which children go on to thrive and which struggle in the wake of exposure to violence. Kasparek brings those questions—and many others—to his research as a PhD student in clinical psychology at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

“Does experiencing violence as a child, either directly or indirectly, influence the development of biases that help us establish trust and close bonds with in-group members?” he asks. “Do these differences in bias influence the development of mental health symptoms over time?”

Kasparek’s 2023 Harvard Horizons project, "Differentiating 'Us' from 'Them': How Violence Impacts Mental Health by Changing Our Perceptions of Others," explores the ways that violence can shape bias—and bias can shape mental health throughout a child’s development. His goal is to inform the effort to improve care for kids at risk for depression, anxiety, and other challenges to their flourishing.

In Group on the Outs

Professor of Psychology Katie McLaughlin, Kasparek’s dissertation advisor, says that membership in social groups confers many benefits for well-being. Along those lines, we as humans have evolved to favor those who are similar to us relative to those who are different. But she says we know very little about how the processes that help us distinguish between “us” and “them” and develop bonds to members of our in-groups might be influenced by experiences early in life or contribute to the emergence of mental health problems. “To our knowledge, no one has previously examined the role that social categorization processes might play in the emergence of mental health problems in children and adolescents,” she says.

McLaughlin supervised a five-year study facilitated by Kasparek that followed children from age 5 to age 10. The team collected data in three different waves: at ages 5 to 6, 7 to 8, and 9 to 10. In the first wave, they conducted in-depth interviews with caregivers about their children’s exposure to violence and collected data from many self-reported questionnaires. During the second, they gathered information about participants’ mental health, using a variety of assessments. “That was to establish a baseline, knowing that down the line we're going to be looking at changes over time,” Kasparek says.

The team also administered an implicit bias test to the children during the second assessment, testing for a psychological effect known as minimal group bias.

“On the basis of minimal information—for example, simply telling someone that they’re going to work on a team with others who have personality traits similar to theirs—people strongly favor the members of that group, even if they’ve never met them,” he says. “This is because we as a social species are evolutionarily primed to want to establish trust, build new connections, and belong to social groups. So, we randomly assigned kids to groups, telling them only that the members liked the same toys and food as they did. And the kids did show strong in-group bias, as we expected.”

When Kasparek’s team looked at the data closely, though, they found that there were differences in how strongly participants favored members of their group. “Kids who experienced violence still expressed in-group favoritism, but not at the level we would expect compared to those who didn’t,” he says. “They showed a weaker, more ambivalent bias.”

Kasparek says that there may be something about experiencing violence, particularly at home, that creates a sense of distrust, caution, or even hypervigilance among children. “These kids may need either more or different kinds of information to say someone is safe or is an in-group member compared to kids who haven't had these early experiences of violence.”

This pattern of reduced in-group favoritism was associated with increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression over time, suggesting that it could place children at risk for certain types of mental health problems in the future.

—Professor Katie McLaughlin

During the final wave of data collection, Kasparek’s team reassessed participants’ mental health. They found that kids who’d expressed reduced in-group favoritism had more internalizing mental health problems—symptoms of anxiety and depression. Kasparek says the reason may be that a more ambivalent preference for new people—a sort of baseline distrust—may make it harder for violence-exposed children to form close connections with others, leading to feelings of loneliness and/or social anxiety.

“School-age children are put in new classroom settings every year,” Kasparek says. “They have new extracurriculars, clubs, and other activities. Maybe some of their classmates carry over from prior years, but they're meeting new kids and adults. If they’re having a harder time with new people, establishing trust, establishing connections, that may set them up for a long trajectory of social and emotional difficulties.”

McLaughlin says that Kasparek’s research is the first to demonstrate that exposure to violence in childhood might shift fundamental aspects of how we categorize other people as “us” versus “them.” “This work indicates that children who experience violence are less likely to implicitly favor members of their in-group than children who have never experienced violence,” she says. The study also advances understanding of the factors that influence youth mental health. “This pattern of reduced in-group favoritism was associated with increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression over time, suggesting that it could place children at risk for certain types of mental health problems in the future.”

Getting Granular

Kasparek is now trying to get a deeper understanding of the relative ambivalence that violence-exposed children feel towards in-group members. “We want to know more about what the process is like,” he says. “Is it distrust driving these effects? Is it something else we haven’t considered yet?”

Kasparek has also launched an online study that will employ a “kin group” model rather than simply a minimal group model, to gauge the impact of violence that occurs specifically at the hands of family members compared with violence that is perpetrated by outsiders. He says that right now, it’s difficult to connect the work to the type of implicit bias we're more familiar with—bias based on race or gender identity—but finds the prospect of working on that sort of research in the future exciting. “We’re trying to figure out how far this effect goes,” he says. “Is it limited to this very broad minimal group context or can it get more specific to the person who perpetrated harm and their identities? You could fashion an entire research career by getting really specific and granular with the different pieces of this. At least, I hope to!”

Kids who experienced violence still expressed in-group favoritism, but not at the level we would expect compared to those who didn’t.

–Steven Kasparek

By studying violence and other risk factors for youth mental health, Kasparek hopes that his work will enable clinicians and educators to design more effective preventive services as well as interventions that might be implemented in schools. The research that underlies such advances is often painstaking and slow, but he says that the children he encounters give him all the inspiration he needs to keep going.

“These kids who we've spoken with—even the ones who have experienced things that would be unimaginable to us—they are so resilient,” Kasparek says. “The fact that they are even going to school regularly and have some semblance of a normal life is really encouraging. And the majority end up functioning quite well and leading meaningful lives. I just want to help those who struggle a little bit more along the way move toward wellbeing and have a better shot at thriving.”

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation Research Fellowship and the National Institutes of Health.

Photo by David Salafia; banner courtesy of Shutterstock

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast