Why Bias Is Bad for the Bottom Line

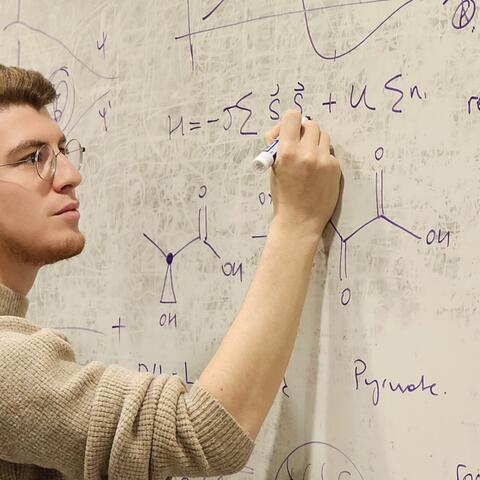

Sophie Calder-Wang, PhD candidate in economics, says that venture capital firms see financial gains when they hire women.

The innovation economy is good, right? New startups provide jobs, grow sectors of the economy, and provide consumers with new and improved technology. But PhD candidate Sophie Calder-Wang asks a bigger question: Is the innovation economy fair?

To answer this question, Calder-Wang decided to put the venture capital (VC) industry under a microscope. In 2017, according to data from PitchBook, only 2 percent of VC dollars went to women. Last year, Forbes magazine reported that less than 1 percent of VC-backed company founders were Black. And, as of 2018, only about 10 percent of new hires by VC firms were women. Calder-Wang says that while we might immediately think of this as a social problem, it’s actually problematic for the economy.

“If you look where growth is coming from, you’ll see more than half of the IPOs [initial public offerings] are coming from venture-backed companies,” says Calder-Wang. “So, it’s very important to make sure the venture capital industry functions.”

The Daughter Effect

Calder-Wang says that diversity isn’t just a social good, it also helps the venture capital firm’s bottom line. It’s difficult, however, to measure whether diverse hires are “window dressing” or a part of firm culture.

“You’ll see high-performing firms are more likely to hire a more diverse workforce, but those firms are also just run better,” says Calder-Wang. In other words, this might be correlation, not causation.

To overcome this problem, Calder-Wang and Paul Gompers, the Eugene Holman Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, decided to compare the behavior of investors who had daughters with those who did not. Other studies had shown that people with similar political inclinations vote differently when they have daughters, so what if the same held true in venture capital?

Gompers and Calder-Wang tracked whether the companies’ investment deals resulted in an IPO or a profitable acquisition.

“We found that, first of all, partners who have more daughters on average hire slightly more women. We also found that these firms perform slightly better financially. Since you can’t control the gender of your children, this allows us to conclude that diversity is indeed good for performance and is not just correlation,” says Calder-Wang. “We’re not saying that people should have daughters. This is just one tool for us to study the question. But, it does suggest that the experience of raising daughters may have an impact on reducing potential gender bias,” clarifies Calder-Wang. She hopes that firms will use this insight to question their own hiring biases, and put more effort into hiring a diverse workforce.

Overcoming Bias

Calder-Wang’s research points to a strong homophily in VC firms, where investors are much more likely to invest in those who share their demographic characteristics, like race or gender. Since hiring in this industry is mostly informal and based on social networks, it can be a challenge for those without connections to gain traction.

“Informal processes advantage the ones who are in the in-group,” says Calder-Wang. “When you make processes more transparent and open, you tend to give an opportunity for those who are not.”

While Calder-Wang acknowledges that no person can be entirely free of bias, she believes that managers owe it to themselves and their companies’ profitability to enact institutional change to better recruit qualified women and minority candidates.

Calder-Wang acknowledges that all people have some amount of bias. She asks VC partners to imagine how they would approach the hiring process if they were truly bias-free. “If you turn yourself into a machine and think about your objectives as an investor, are you going to make the same kind of snap judgments?”

Progress Affects Our Lives

Calder-Wang plans to continue to explore questions around the human side of the innovation economy.

The spark that inspired Sophie Calder-Wang’s research came from her father, who worked as an entrepreneur in the semiconductor industry during the 1980s. At first, he had terrific success, but his business floundered when he failed to keep up with the latest technological trends. Watching her father’s struggle impressed upon Calder-Wang the challenges of pursuing an entrepreneurial career in a volatile industry, and made her want to ask more questions about how the innovation economy has a direct impact on people’s livelihoods.

“I’m blessed that I have the opportunity to look at it from a social scientist’s perspective,” says Calder-Wang.

Calder-Wang’s research is supported by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University and a winner of the Kauffman Knowledge Challenge.

Photo by Joshua Chiang

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast