Veritalk: Displacement Episode 1 - The Rohingya

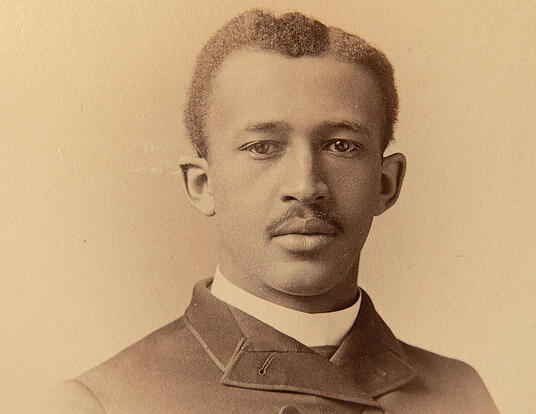

Very few outsiders have been to Northern Rakhine state, where more than 140,000 Rohingya Muslims are living in internally displaced persons camps. But Cresa Pugh, a PhD student in sociology and social policy, has been there. On this episode of Veritalk, she shares what she's learned about the lives of displaced Rohingya Muslims, and why persecution of the Rohingya continues in Burma.

Find new episodes of Veritalk on Apple Podcasts.

Full Transcript

Voices: I mean, why?

Anna Fisher-Pinkert: From the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, you’re listening to Veritalk. Your window into the minds of PhDs at Harvard University.

Overlapping voices

AFP: I’m Anna Fisher Pinkert. And, in this mini series, we’re talking about Displacement. Why and how do people get set apart from their communities? As always, we’re going to answer that question through the research of PhD students in different fields at Harvard. We’re going to start in Burma.

Newscaster: Hated and hounded from Burmese soil, hundreds of Rohingya Muslims have made it to Bangladesh.

AFP: Before I recorded this episode, I typed the word “Rohingya” into Google. R-O-H-I-N-G-Y-A.

Second Newscaster: More than 500,000 Rohingya refugees. . .

Third Newscaster: 625,000 Rohingya refugees have fled. . .

Fourth Newscaster: Life continues to be a misery. . .

AFP: Those headlines are all that most Americans know about the Rohingya.

Translator: Where are we supposed to live?

AFP: Frankly, even if you make the trip to Burma, it's hard to learn much more about what's going on with the Rohingya people. It’s nearly impossible to get to parts of Rakhine state, where 140,000 Rohingya live in Internally Displaced Persons camps or IDP camps for short. But Cresa Pugh actually went to Northern Rakhine on a research trip. She's a PhD student in sociology at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Cresa Pugh: I was there in June and July and the the most recent crisis and displacement start in August is actually before the most recent kind of like large scale kind of mass exodus but still a lot of the NGOs had been kicked out of the region. And so I go, and I'm basically like the only. . . I think I saw one other foreigner while I was there I was there for about a week in this particular area and literally the only person, and so I just stood out.

AFP: The Rohingya people are from Rakhine state, a part of Burma that borders Bangladesh. They’re a minority community in Burma, where the dominant religion is Buddhism. Cresa is looking at both sides of the conflict. And that conflict is complicated, and really old.

CP: The history of the conflict is really quite disputed. There's really no kind of authoritative history, and I think that's actually part of why the conflict is happening -- because this history is so disputed. Some people would say that you know the arrival of Islam to Burma in the sixth century AD is when you really need to start tracing the history to really understand why we're in the situation where we are today.

AFP: But others would point to colonialism as the root of the modern-day ethnic and religious conflict in Burma.

Newscaster: The British who colonized Burma in the early 19th century. . .

AFP: The British colonized Burma in the early 19th century through three successive wars.

CP: The way in which they thought of religion, and kind of imposed their understanding of religion, was very much intuitive and disruptive to the way that the Burmese and other ethnic groups had understood religion prior to the British arrival.

AFP: Prior to the arrival of the British, religion and politics in Burma were pretty intertwined. And there weren’t necessarily really strict definitions around religious identity. But the British loved categories.

CP: They also kind of codified these notions of what religious identity look like. So they kind of reified identities of other groups, too. So, "Muslim," "Christian," "Buddhist," . . . these categories, which were much more fluid prior to 1824; there were hard lines drawn between these religious categories.

AFP: The British eventually left when Burma gained its independence in 1948.

Newscaster: In Rangoon itself, 4:20 a.m. was the hour affixed by Burmese astrologers as the most auspicious time for the transfer of power.

AFP: But those categories stuck around - particularly for ethnic and religious minorities like the Rohingya.

CP: According to the Burmese constitution there are 135 "races" of Burma, and there have been times that the Rohingya have been considered a national race of Burma, and there are times that they haven't been. And so, right now, particularly as of 1982, there was a citizenship law that was passed that basically bars the Rohingya from citizenship. Since then, really, in this nation-building project, they've been very much excluded. And that's because of this exclusion, the legal exclusion, that's kind of provided the basis through which a lot of the discrimination, a lot of the violence against them has taken place.

AFP: So one of the things that one of the things that it's kind of confusing in my mind is that there are Burmese who are Muslim who are not Rohingya who are included in government and politics and in those groups of recognized people. Why are the Rohingya singled out.

CP: Yeah. So there are a number of other different Burmese Muslim groups that are not Rohingya. They are much smaller. The Rohingya are actually the largest population, numbering roughly a million individuals within the country. They're definitely the largest group of Muslims in Burma. The Rohingya are kind of less integrated in society. So a lot of people will say because they don't speak the traditional dialect of Burmese, they speak their own Rohingya language.

AFP: Rakine state, where both Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims live, is also separated from the rest of Burma by a mountain range. It’s actually easier to get to Bangladesh from Rakine state than it is to get to much of the rest of Burma.

CP: There are arguments that because of the geographic marginalization and isolation of the Rohingya that they've had a harder time of being incorporated into the state, which is also the story of like a lot of other ethnic minority groups within Burma, because they mostly all live kind of on the periphery, on the margins.

AFP: Being a stateless ethnic minority puts the Rohingya in a difficult position, and continued waves of violence against them, some of which have come from the military itself, has led many to flee.

CP: About a million of them have fled to Bangladesh over the last probably two decades, but 140,000 of them are still in Burma. Some of them are actually displaced within their own cities. Until 2012 in the city, in Sittwe, and in other cities around Rakhine State, Rakhine Buddhists and the Rohingya Muslims lived together. They weren't particularly integrated. They had kind of separate quarters within the neighborhoods, but the cities were relatively mixed.

AFP: Then, in 2012, a series of riots broke out in Rakhine state, kicking off a wave of violent conflict between Muslims and Buddhists, which in turn led to action by the Burmese military - a group that has a history of violence toward the Rohingya.

CP: The Muslim quarters - one in particular, Nasi in Sittwe -- was actually surrounded by guards, by the military, by the police. They literally, overnight, constructed barbed wire and created a camp within the city.

AFP: Six years later, the Muslims who lived in this quarter - just 25 or 30 blocks - are still confined there.

CP: And then the Muslims who lived in other quarters kind of outside of this area those were the ones who displaced to the IDP camps and it was those IDP camps that I visited.

AFP: Unlike refugee camps outside of Burma, which are run by external organizations like the UN, the IDP camps in Burma are run by the Burmese government. Cresa wanted to see for herself what was happening, and that’s how she got permission to go to an IDP camp in Northern Rakine state.

CP: It was really just devastating and alarming to see the conditions of the Rohingya camps because, you know they're desperate. You have families that are living like eight to ten in a house sleeping on mud floors. Fake guns were really quite popular and quite common. Like as children's toys, but also adults would just be kind of carrying around these fake guns. And so just the degree to which these environments have been really militarized just struck me. I was conducting an interview and at one point like this little kid who couldn't have been more than like three or four came in with a gun and just kind of shot at me for good like five minutes as I was doing an interview. It was just this very surreal experience. The community is really worried about primarily freedom of movement and education were kind of the top two, and freedom of religious practice were kind of the top three issues that people cited as being their major concerns: When are we going to get out? When are we going to be able to resume our daily lives outside of the camps? They're not allowed to work, and so they're literally just languishing away in these camps.

AFP: But getting to the camp was, in some ways, just as harrowing.

CP: I took the boat up there. It was like a four- or five-hour boat ride.

AFP: There was a movie on the boat, playing for the whole ride. The movie is based on a real-life rape and murder of a Buddhist woman, allegedly committed by Muslim men in 2012.

CP: And that's actually what kicked off the riots of 2012. And they've since made a movie about this, and they show this movie on the boat when you're going to this area where the a lot of the violence actually happened to essentially inflame the people. So when they get to this predominantly Muslim area, they've just seen like literally just like hours of footage of like this like a young girl being raped by Muslim men. There's a narrative that's been spun that Buddhism is under threat. That Buddhist women are being raped and killed. This narrative has been very like skillfully deployed by now by the media, by monks.

AFP: So Cresa asked Rakhine Buddhists what they thought about the Rohingya.

CP: I’d tell them that I was going into the camps. And =I would tell them what =I was seeing and they just automatically denied it. They were like, "Well, we've heard that they have it better than us. You know we heard that the government, the UN are giving them more food, better food. You know, better materials to build their houses. The media and social media has kind of constructed this this idea that the Rohingya are like not individuals that are persecuted. The narrative that's very common in Burma is that the Rohingya are actually there illegal immigrants from Bengal/Bangladesh. That are not indigenous to Burma, that are basically here to steal the land that doesn’t belong to them that never belonged to them.

AFP: The Rohingya have been in Rakine state for generations. But Cresa thinks erasing that history makes it easier to justify the treatment of the Rohingya today.

CP: I think the idea of this idea of erasure has been really, really important in the government's and the military's and the general public's attempt to really really kind of carry through this kind of like slow burning genocide that we're seeing.

AFP: Cresa says the Buddhist she talked to didn’t just deny the day-to-day desperation of life in the camps, they denied the Rohingya identity.

CP: So people don't call the Rohingya "Rohingya" in Burma because to name them means to acknowledge their existence as an ethnic group within Burma. And so and they're referred to as Bengali illegal immigrants. You know they're referred to as "kalar" which is an ethnic slur for this community. But they're not referred to as Rohingya. Refusing to name someone kind of puts them slowly outside of the circle of recognition. Denying their identity, denying the realities, then makes people say well, “oh you know, this group exists at the margins. There must be a reason. It must be kind of their own shortcomings it must be because like they're new to the country and they haven't earned their right to be in a politically socially economically engaged."

AFP: Right now, you might be thinking about how this logic has been applied to minority groups in other countries - maybe even in the United States. Cresa has been thinking about that, too. She told me about a 2014 study in which New Yorkers were shown statistics about the percentage of the prison population that is made up of black men. So, that's either 40% nationally, or 60% in New York City. And just looking at a higher number, that 60% statistic, made New Yorkers more likely to report that they were concerned about crime, and less likely to sign a petition against stop-and-frisk policies. Cresa thinks that seeing evidence of inequality doesn’t always change people’s minds about where that inequality comes from.

CP: So I think the same thing happens in Burma, with the Rohingya. People kind of see the Rohingya, and they hear about them being in camps, and they hear about them having to flee to Bangladesh and they're like, "well it must be something that they've done." We can't have sympathy towards them. They've created the situation themselves. You know, whether it's that they're lazy, they're here illegally, whatever it is. It's that narrative that their condition can only be explained by their own actions.

AFP: This leads to a vicious cycle in which the Rohingya are marginalized, their stories are erased, and then they become further marginalized. If you ask Cresa if there’s an end in sight. . .well, there’s no easy answer.

CP: 700,000 Rohingya have fled Burma to Bangladesh primarily since late August 2017. And, you know initially kind of in the months of September, October, November, people were really concerned about making sure that when the Rohingya return to Burma that they don't go back into the same situations that they left. That was kind of the conversation a few months ago. Now we're realizing that return actually isn't really looking like an option. A lot of the villages from which the Rohingya fled are being bulldozed. They’re actually building new homes and villages that are Rakine Buddhist-only, literally on the remains of these burned Rohingya villages.

AFP: What happens when a group of people is displaced, and return isn’t possible. What happens after two generations - or three - live out their lives in a state of displacement? What sort of culture emerges from a displaced people? Next time on Veritalk, we’re going to talk about the literature and art of displacement.

Argyro Nicolaou: The place that you left behind changes the moment you leave. Your imagination has to compensate for all the "what-if's," "what is it like now." There are imaginary and alternative geographies that are built through these narratives of Displacement.

AFP: Veritalk is produced by me, Anna Fisher-Pinkert at the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Our sound designer is Ian Coss. Our logo is by Emily Wilson. Our executive producer is Ann Hall. You can find new episodes of Veritalk wherever you get your podcasts or at gsas.harvard.edu.

Logo by Emily Wilson

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast