Faith Seeking Understanding

How Christianity and Hinduism influence each other in India

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

Akhil Thomas held his pregnant mother’s hand as they took shelter from a fierce monsoon. They stood under the tin roof of a cobbler’s shop, two Indian Christians in the overwhelmingly Hindu megacity of Delhi. After a time, Thomas’s mother turned to her four-year-old son and asked an unexpected question.

“She said, ‘You are going to have a brother soon, what would you like to call him? Think of a good name, but it can’t be a Christian name,’” Thomas remembers. “As it was in some other communities, having a traditional Hindu name was a way for non-Hindus to hide. So, my parents named my brother Nikhil.”

Today, Thomas seeks not to hide but to reveal. As a PhD student in religion at Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, he studies Hinduism and Christianity, illuminating the influence the traditions have had on each other in his home country in order to expand our understanding of both. In so doing, he hopes to help improve interfaith dialogue in an age of religious nationalism and polarization.

Caste Out

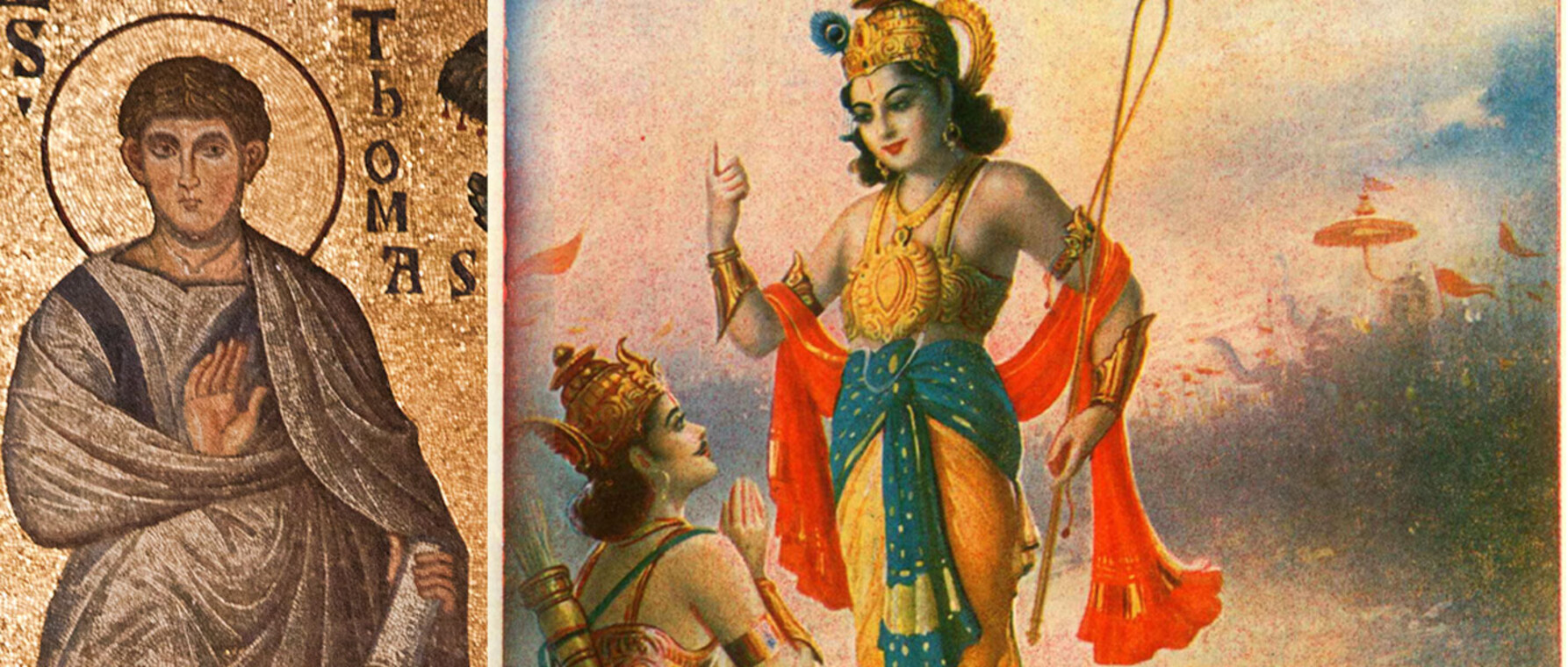

Thomas is a member of one of the oldest Christian communities in the world. The Syriac or Malabar Christians of the Kerala state on India’s southwest coast believe that the Apostle Thomas arrived at the popular trading center in A.D. 52 when he evangelized among the local population and established eight villages there.

“My family is part of a small community who were converted and have always been a minority in southern India,” Thomas says. “It’s been running for 2,000 years now and for long periods was completely disconnected from large international church centers. We were largely isolated from the churches of both the East and West until the 16th century.’

Thomas’s parents were the first in his family to move from the tight-knit community in Kerala away to Delhi, where he grew up. Although they could, to some extent, hide their children’s religion by giving them Hindu first names, they couldn’t hide the color of their skin. Dark-skinned Indians like them were associated with the lower levels of the Hindu caste system, which, Thomas discovered, had a profound influence on his life even though he was a Christian.

“I realized quite early on that that the color of my skin situated me within the Hindu caste structure,” he says. “There is an ongoing debate about Thomas Christians claiming upper caste origins in South India. However, caste works in more complicated ways and became more complex with my growing up in northern India.”

Caste shaped not only Thomas’s wider life in Delhi but also projected its hierarchy and strictures on the Indian Christian community of which his family was a part.

“Indian Christians are fully in Indian society,” he says. “It’s a diverse community that falls along various caste identities. There are Christians who are considered dominant caste and there are Dalit Christians [Hindu converts] who are considered lower caste. The color of the skin has historically been used as a marker to make these distinctions, in addition to various other factors in South Indian society. And it’s not limited to Hinduism and Christianity. Muslims, Jains, and Sikhs all fit neatly into the larger caste system.”

Hinduism’s influence on his tradition left Thomas perplexed. How did caste structures seep into a Christian community in the first place? How did the two traditions influence one another? He brought those questions with him to prestigious St. Stephen’s College in Delhi, where he sought a deeper understanding of Indian philosophy, particularly Advaita Vedanta, a school of Hindu thought and theology. After graduating with both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in philosophy, Thomas enrolled at Yale Divinity School, where work in comparative theology helped him to rediscover his own faith.

Indian Christians are fully in Indian society. It’s a diverse community that falls along various caste identities.

“Theology is faith seeking understanding,” he explains. “At Yale, I had the insight that learning from a different faith not only helps me to understand that tradition but also helps me to understand my own. Because Indian Christianity is deeply influenced by some of Hinduism’s concepts and practices, I found that I could revitalize my understanding of my religion as I studied the multiple Hindu traditions.”

Thomas continues this work at GSAS with the support of his faculty advisor, Parkman Professor of Divinity Francis X. Clooney, a Jesuit priest and one of the world’s leading Hindu-Christian comparative theologians. A deep dive into two religions might seem daunting, given that theologians have spent lifetimes exploring the contours of just one, but Thomas takes heart in the fact that he has a lot of company in his task.

“The beautiful thing is that people have always been doing comparative theology,” Thomas says. “Religions constantly interact and shape each other. You can’t talk about Christianity in America without talking about Judaism. In India, you can’t talk about Christianity without Hinduism. Religions in their local expression are continuously surpassing the understanding of institutions like universities.”

Blurred Boundaries

As an example of this complexity—and the consequences that follow from a failure to embrace it—Thomas points to one of the most traumatic experiences in the long history of Indian Christians: the arrival of Portuguese traders in the 16th century. Thomas says that the Portuguese came looking for “Christians and pepper.” They found the spices, but the Christians of South India behaved and believed very differently than the Europeans did.

“The Portuguese accounts said that the Indian Christians believed in reincarnation,” Thomas says. “They said that they believed in fate and universal salvation. So, the Portuguese said, ‘This is not what the Catholic Church believes. We need to rectify these mistakes.’”

At the Synod of Diamper in 1599, the Roman Catholic Church sought to do just that, subjugating the Malabar Christians under the diocese at Goa, which was administered by Catholic missionaries. The synod also established a raft of new religious laws, for instance, banning the marriage of priests and the celebration of Hindu festivals. The result was a schism in the Keralan community between those who joined the Latin church and those who adhered to the traditional beliefs and rituals. It lasts to this day.

“The Portuguese wanted to see Christianity in their own image and likeness,” Thomas says. “They wanted to see Portuguese Christianity in India and it wasn’t that at all. It was a rude surprise for them and a very bad event for Indian Christians. The Portuguese burned many of their ancient manuscripts.”

The Europeans’ great failure, Thomas says, was their inability to see Malabar Christianity as an Indian religion—one deeply rooted in the wider society and culture and shaped by its relationship to Hinduism. By employing a broader perspective and a sense of theological imagination, Thomas makes connections between doctrines that at first seem impossible to reconcile.

“A major part of my work is reconsidering Christian and Hindu beliefs that seem contradictory,” he says. “Take reincarnation, one of the beliefs that the Europeans wanted to eradicate. Christians believe that there is only one life. Hindus believe that we are reincarnated in different forms until we are liberated. But Christians do believe in a kind of continuity of life. That’s why we sometimes plant a rose garden where we bury our dead. We don’t believe that life ends right there. The lines are more blurry than we like to think.”

An appreciation of the blurred boundaries between religions, Thomas says, enables better interreligious dialogue and helps overcome the religious nationalism that has surged in India, the United States, and elsewhere in recent years.

“We hear of bombings in mosques and on Easter in churches,” he says. “Those stem from a denial of the complexity and pluralism of the world. Comparative theology is an acknowledgment of that complexity. It’s an understanding of the fact that religions do not develop in isolation from each other. It’s reading the scriptures of every tradition as scriptures, not as ‘what the natives are doing.’ Comparative theology enables us to see what’s beautiful in another religion.”

[Like Hindus], Christians do believe in a kind of continuity of life. That’s why we sometimes plant a rose garden where we bury our dead. We don’t believe that life ends right there.

Clooney, who sits on the faculty of Harvard Divinity School and serves as Thomas’s advisor, says that the student’s life experience and identity—as well as his rigor as a scholar—enable him to offer new insights into religion, culture, caste, and education in India and the West.

“Akhil, writing from a Kerala Christian background and having grown up in Delhi, of course sees Christianity in India through his Indian eyes,” Clooney says. “He wants to go deeply into the old Christian traditions of Kerala, such as were there before the Portuguese arrived, and study their relation to Hindu communities. It is a fresh starting point for theology and comparative theology.”

From this starting point, Thomas hopes in the years ahead to explore theologies that reflect the ways that religion is actually lived in an increasingly multireligious world. By studying Christianity in India—where faith communities interact, mix theologies, and shape each other’s rites and rituals—Thomas says that we can move beyond rigid doctrine and orthodoxy and learn to embrace difference.

“Congruence isn't what the believer strives for,” he says. “The believer does not think in propositions. We do not go to our churches and places of worship thinking, ‘This concept does not go together with that concept,’ or ‘How can I believe this?’ We have to think better about how our religious lives are lived so that we can better live with each other.”

Photos by Tony Rinaldo; Banner Images Courtesy of Flickr

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast