Deadly Force

The impact of aggressive policing on communities of color—and public health

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

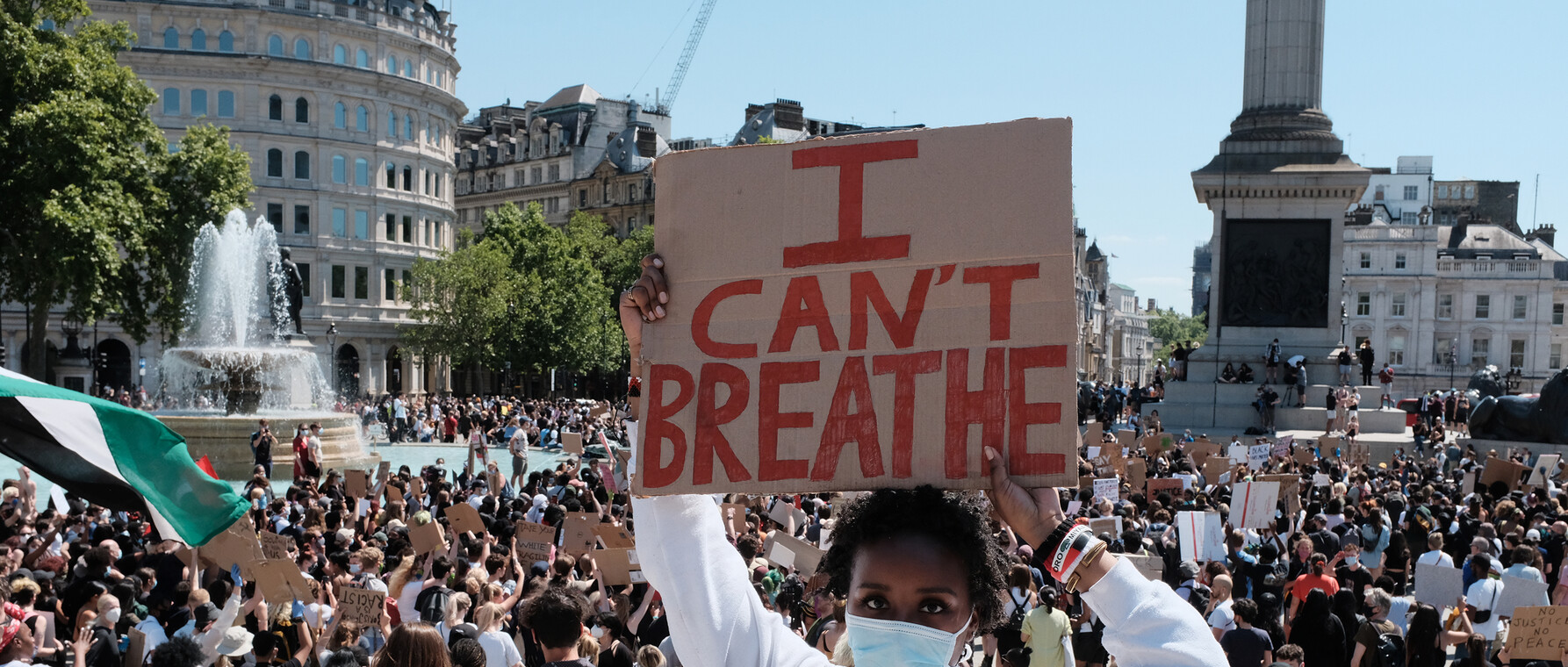

Soon after Jackie Jahn, PhD ’20, graduated from GSAS, then-US Attorney for the District of Massachusetts Andrew Lelling described calls to defund the police as “ridiculous” at a June 2020 press conference. Lelling went on to praise law enforcement for “enormous strides” in the quality and professionalism of its work in recent years, to which he attributed the “historic lows” in crime rates across the country. He called accusations of systemic racism in police departments “vague and unanalyzed” as well as “misguided.” Lelling’s remarks came a few weeks after the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by Minneapolis police—an event that sparked nationwide protests and inspired millions to participate in the movement for Black lives.

A social epidemiologist steeped in data about policing, Jahn watched a video of the press conference months later and bristled at Lelling’s remarks.

“The most glaring example of the public health impact of policing is in communities of color,” she says. “There are wide racial disparities in terms of who’s stopped—and sometimes killed—by police.”

Now a postdoctoral scholar at the City University of New York’s Stone Center on Socio-Economic Inequality, Jahn studies policing as a public health issue with particular attention to its effects on traditionally marginalized communities. Through her work, she hopes to advance understanding of the health harms of the criminal justice system and to inspire policymakers to imagine new alternatives.

On average, Black people were more than three times as likely to die at the hands of police than were white people.

Fatal Encounters

Jahn says a growing body of epidemiological research shows that residents of neighborhoods subjected to heavy-handed policing face dire health consequences. She points to “Risk of Police-Involved Death by Race/Ethnicity and Place, United States, 2012-2018,” a recent study from researchers Frank Edwards, Michael Esposito, and Hedwig Lee indicating that between 2012 and 2018, police accounted for more than 1 in 12 of all homicides of adult men. During that time, police-related fatalities killed more Black men in their 20s than diabetes, flu/pneumonia, chronic respiratory disease, or cerebrovascular disease. At that rate, she says, 1 in 1000 Black men can expect to die of police violence.

One of the greatest obstacles to addressing fatal police violence from a public health standpoint is the lack of basic information about where and how often it occurs. As a remedy, Jahn and her colleague Gabriel Schwartz—both graduates of GSAS’s PhD program in population health sciences—set out to map police killings in metropolitan statistical areas across the United States that took place between 2013 and 2017. Because the federal government doesn’t gather comprehensive information on these killings, the two turned to data collected by Fatal Encounters, a nonprofit that works to create an accurate account of police killings nationwide.

“Many studies—including those from my mentor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School, Dr. Nancy Krieger and her colleague Dr. Justin Feldman—have documented a systematic underreporting of these deaths in federal statistics,” Jahn says. “Fatal Encounters aggregates news reports, validates them with public records, and has a team of researchers that makes sure the information on each incident is correct. It’s very widely used by scholars.”

Excluding deaths classified as suicides, accidents, and vehicle collisions as well as those for which no information on race and ethnicity was available, Jahn and Schwartz tallied nearly 5,500 police killings over the five-year period. From that database, they created two maps—one of police fatalities per 100,000 inhabitants in metropolitan areas across the US and one that charted the racial inequities in those killings. (Pictured below.) The disparities they found were striking.

“On average, Black people were more than three times as likely to die at the hands of police than were white people,” Jahn says of the research she and Schwartz published in June 2020 in the journal PLOS One. “In some metropolitan areas, the ratio was much higher. Black people in Chicago, for instance, were 6.5 times more likely to be victims of fatal police violence.”

Moreover, although white people comprise 60 percent of the US population, they accounted for just under 43 percent of those killed by police from 2013 to 2017. Over 44 percent of people killed by police during those year were Black or Latinx, who represent only 30 percent of the country.

Jahn and Schwartz also found geographical patterns that surprised them.

“We found some of the highest Black-White racial inequities in fatal police violence in the Northeast, which was not something we expected,” Jahn says. “And the overall rates of fatal police violence were very high in California and the Southwest.”

The Risks of “Stop and Frisk”

Jahn says more research is needed to explain regional patterns and get an accurate picture of police violence in the US. In the meantime, she is broadening her exploration of the health impacts of contact with law enforcement. Her latest work, published in The Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, is a study of the mental health of adolescents stopped by police between 2002 and 2007.

“Around one in ten adolescents reported being stopped by police two or more times in the previous six months,” she says. “Over 20 percent of Black adolescent boys reported that they were stopped by police two or more times in the last six months. We controlled for a wide range of socio-economic and other variables and found a measurable relationship between contact with law enforcement and depressive symptoms, particularly among girls whose parents had been incarcerated.”

Krieger, professor of social epidemiology at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, was Jahn’s faculty advisor during her time at GSAS. She says that her former student’s latest work adds depth and nuance to scholars’ understanding of aggressive policing as a form of structural racism that perpetuates health inequities.

“To date, the limited research on public health harms due to police violence has focused chiefly on adult mortality due to police killings and available national data on police-public contact does not extend below age 16,” Krieger explains. “The contribution of Jackie’s study on frequent police stops in relation to adolescent psychological well-being is the first such study to be conducted in a nationally representative sample. Its findings reveal the importance of considering simultaneously both racialized group and gender.”

While Jahn contributes to scholarship in her field, she also seeks to influence the way that policymakers think about criminal justice and public health. To that end, she co-authored the American Public Health Association’s policy statement, “Advancing Public Health Interventions to Address the Harms of the Carceral System,” which lists 13 action steps that governments and agencies can take to “move toward the abolition of jails, prisons, and detention centers and to build in their stead just and equitable systems that advance public health and well-being….” These include safely reducing the number of incarcerated individuals to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, removing obstacles to employment and housing for the formerly incarcerated, restoring voting rights, and exploring alternatives to incarceration.

Jahn says that the ultimate goal of her work is to get policymakers to see the existing regime of policing and incarceration as a system that is, in many ways, bad for our health.

“We’re calling for an urgent reduction in all those held in detention facilities because of the known harms of those settings,” she says. “This is particularly important now when cases and fatalities related to the pandemic are much higher than in the general population, but that just highlights one of several extreme health burdens that incarcerated people bear. For public health—but also for the sake of basic human decency—we must do better.”

Photos courtesy of Jackie Jahn and Shutterstock

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast