Dammed if They Do

How and why beavers are driven to build

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

At the beginning of time, the world was covered with water. Floating on a raft were Old Man and all the animals. When Old Man decided to make the land, he told the beaver to dive to the bottom of the water and bring up some mud. The beaver tried mightily but came back with nothing—as did the loon and the otter until the muskrat dove deep and surfaced, barely alive, with a little mud in his paws. The Old Man let the mud dry and sprinkled it on the water to create the land.

Though the beaver fails to bring soil to the surface in this creation story of the Blackfeet Nation (Amskapi Piikani) as set down by the naturalist and anthropologist George Bird Grinnell, the fact that the primordial human turned to it first at the beginning of the world gives a sense of the animal’s place in Blackfeet culture. The fact that the beaver is sacred is one reason it thrives today on the nation’s land in northern Montana where environmental engineer Jordan Kennedy grew up.

“The beaver is considered one of the fundamental animals of creation in Blackfeet culture,” she says. “So, when trappers started to expand west, the Blackfeet, who revere the beaver, were not typically willing to help them within their territory. As a result, the animals weren’t wiped out the way they were in much of North America.”

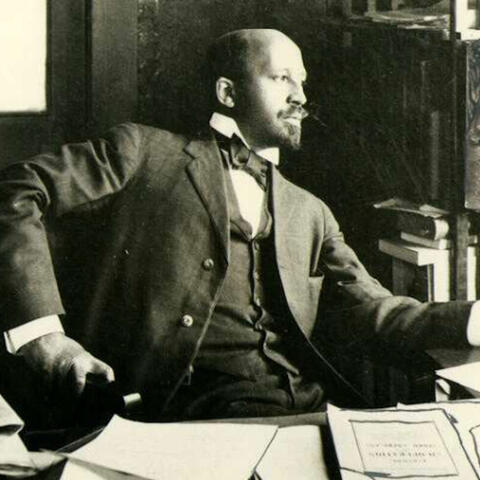

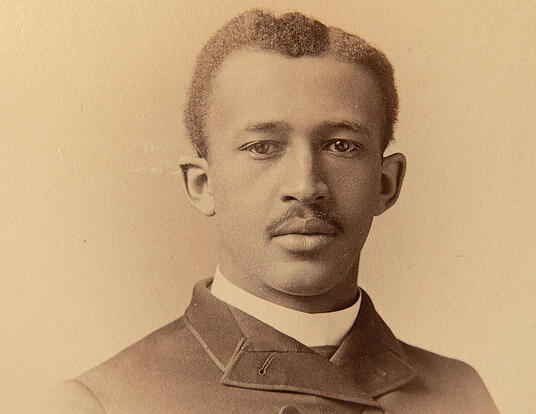

That’s good news for Kennedy, a GSAS PhD student in engineering sciences based at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences who studies how and why beavers build. Her research sheds light on the way individual beaver colonies collectively create extensive networks of dams, canals, and trails without directly coordinating or communicating with one another. In so doing, Kennedy’s work may not only help naturalists better understand animal behavior but also present intriguing models for innovators in the field of robotics.

A Large-Scale Project

Today the beaver thrives in many biomes throughout North America because of the animal’s ability to modify its environment to suit its needs. In the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, where the Blackfeet nation is located, annual floods wash out beaver dams every spring allowing a unique opportunity to watch the colonies rebuild them from scratch. When Kennedy returned to this region as a graduate student she had a simple question: How do beavers build dams? To her surprise, there was relatively little research on the topic—particularly from the perspective of an engineer rather than a naturalist.

“You see beavers kind of working on a dam here and there in wildlife documentaries,” she says, “but not really building one from scratch. There’s a lot of anecdotal evidence from people who've been out in the field and not necessarily from a science perspective. It's a wide-open field of study.”

One reason for the paucity of research on dams is that beavers do their work at night to avoid predators. For that reason, Kennedy herself only occasionally comes into contact with the animals—and even then doesn’t observe them building. Instead, she tracks the formation of dams, lodges, canals, and pathways through photographs taken by drones she flies over Blackfeet territory. Despite her knowledge of the land and wildlife, much of what she’s learned about beavers has come as a surprise—notably, the scale of their engineering operations.

“Beavers can transform an ecosystem thousands of meters in length over a single summer,” she says. “Dams are only a small part of it. They need extensive trail networks so that they can travel back and forth to support material transport for lodges, dams, and food cache construction. They also excavate extensive canals and fell trees right alongside so that they can float them back to the dam. It’s a pretty sophisticated and large-scale engineering project, particularly when you consider that we’re talking about rodents only as big as a mid-sized dog.”

A colony might number six to eight beavers and operate along a section of waterway that’s a few hundred meters long. The sites that Kennedy studies in Montana are home to 20 identified colonies. Together, the animals have constructed a complex network of canals, trails, lodges, and food caches along a waterway nearly four thousand meters long. Kennedy estimates the work has taken decades—perhaps even more than a century—and spanned many generations. Even more remarkable is the fact that it occurred with no central coordination.

“As far as I'm aware, they're not passing down engineering drawings from generation to generation,” Kennedy jokes. “But like termites building a mound or honeybees building a hive, they’re able to construct something at a very large scale. In fact, they build dams at length scales a thousand times larger than an individual beaver and time scales many times greater than the lifespan of a single beaver.”

The kind of indirect coordination between animals based on environmental cues that Kennedy describes is called stigmergy. A termite, for instance, digs up some soil and leaves pheromones on it, which attracts another nestmate who does the same. Multiply by a million or two termites and you get a mound nearly three meters high. In her research, Kennedy explores whether stigmergy applies to beaver behavior.

“I can't definitively say yet that beavers would fall into this idea of collective builders,” she says. “But they certainly hit a lot of the checkboxes to be qualified as individual agents who respond to local environmental cues to collectively create a global damming network. Just look at the length of the networks they create and the time it takes to construct them.”

As far as I'm aware, [beavers] are not passing down engineering drawings from generation to generation. But like termites building a mound or honeybees building a hive, they’re able to construct something at a very large scale.

The Goldilocks Zone

One of Kennedy’s mentors in this research is L. Mahadevan, the Lola England de Valpine Professor of Applied Mathematics, professor of organismic and evolutionary biology and of physics. In 2019, Mahadevan and his team reported that, once a mound is built, termites respond to environmental cues such as air flow and temperature to adjust its architecture. “As Winston Churchill once said ‘We shape our buildings and thereafter they shape us,’” Mahadevan said at the time. “We can quantify this statement by showing how complex structures arise by coupling environmental physics to simple collective behaviors on scales much larger than an organism.”

Beavers are not termites. Besides being much larger and smarter than insects, the mammals’ works take much longer to construct than a termite mound. Moreover, beaver building behavior is not a response to pheromone cues. But Kennedy believes that beavers respond to the flow of water similar to the way that her mentor Mahadevan found termites respond to temperature and the flow of air. While it’s long been suspected by researchers that the sound of running water is a trigger for dam building, though, Kennedy says the reality is likely more complicated.

“If it was just that they hear running water, then beavers would be trying to build across Niagara Falls,” she says. “Other environmental factors work together to create a kind of ‘Goldilocks zone’ where things are just right and beavers are going to build.”

The water in a beaver’s habitat needs to be a certain depth, for instance, to keep a food cache from freezing to the bottom in winter—and to enable them to evade predators. The plants that beavers prefer to eat flourish best when water flows at a certain velocity. Kennedy contends that these factors, as well as the existence of vegetation to eat and build with, are the basis for stigmergic activity among beaver colonies.

“I took measurements and you can see that, when the flow of water is sufficiently low enough, beavers will start building dams,” she says. “So, although my field sites were all more or less in the same location—all on Blackfeet land—beavers started building at different times depending on the flow rate I measured at their particular location. I think the data set shows that flow is a very strong trigger.”

Kennedy’s findings address a much larger question: How big can a stigmergic system get? Her other faculty mentor, Fred Kavli Professor of Computer Science Rhadika Nagpal, has leveraged research on social insects to develop kilobots, “a low-cost, easy-to-use robotic system for advancing development of ‘swarms’ of robots that can be programmed to perform useful functions by coordinating interactions among many individuals.” A reflection of the insects that they imitate, however, kilobots are quite small—only about 33 millimeters in diameter. Beavers are orders of magnitude larger—as are their works.

“The scale that termites operate on is impressive for their size,” Kennedy says. “The scale at which the North American beaver can successfully operate in a decentralized way is much bigger. So, if you're thinking about having a fleet of robots the size of a dog, you can scale the work they do to something more usable by humans.”

Although Kennedy is excited about the implications that her research could have for robotics, she also hopes it will draw attention to the role that beavers play in the natural environment. She points out that naturalists only began to study North American waterways seriously after the beaver had been wiped out across much of the continent by trappers and hunters. For that reason, the effect of their absence on an ecosystem has been poorly understood. Increasingly, though, researchers are asserting that the animals are an important part of the ecology.

“Yes, beavers cut down the trees, but then they bring in all this other plant life,” she says. “A number of papers demonstrate that plants start to flourish and invertebrates start to populate the areas beavers inhabit. Even if you don’t think that beavers are sacred, it’s coming more and more to the forefront how important they are to the health of our waterways and everything that lives there.”

Banner courtesy of Shutterstock; Photos courtesy of Jordan Kennedy

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast