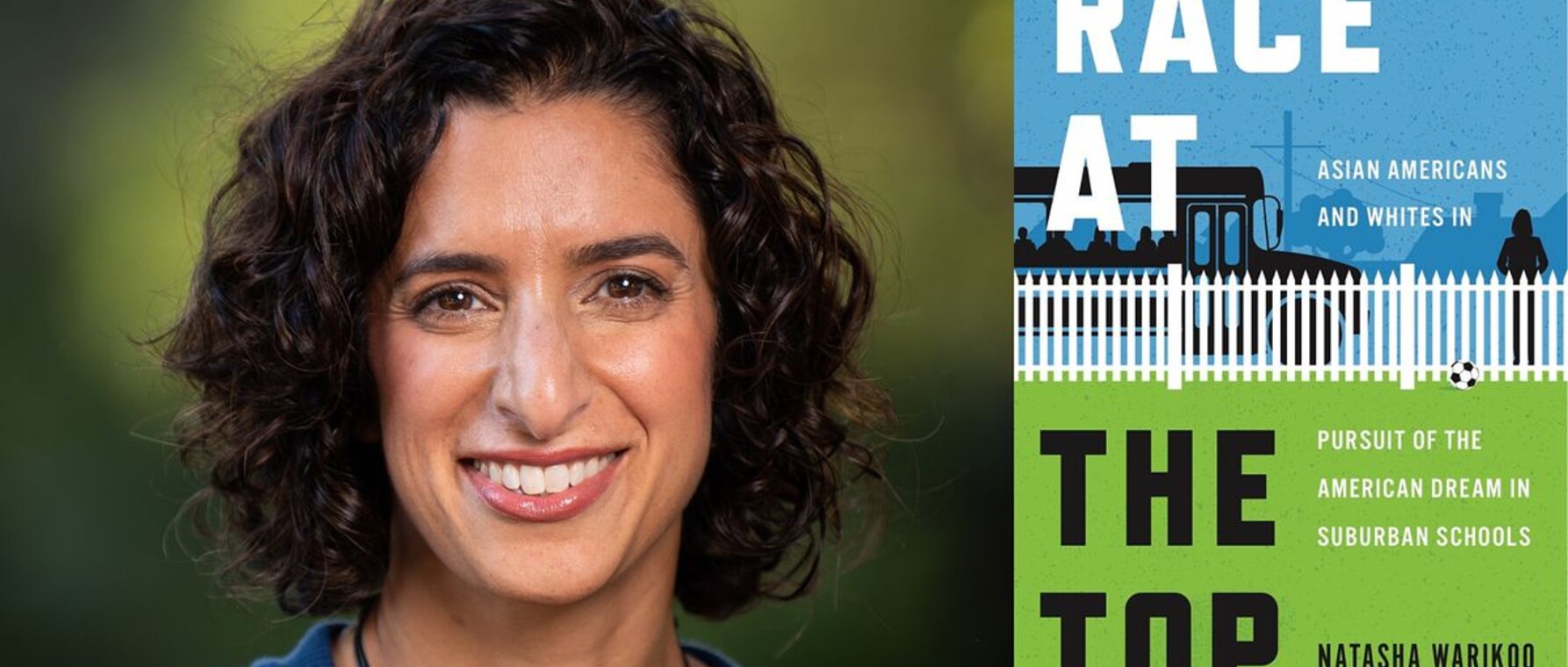

Colloquy Podcast: Race and the Pursuit of the American Dream in Suburban Schools

White and Asian immigrant families clash over public education in a wealthy suburb

“We are living in an age of anxiety,” writes the Tufts University sociologist Natasha Warikoo, PhD ’05, one in which even wealthy families who seem to “have it all” are insecure about their status. Her new book, Race at the Top, explores the ways in which educated, well-to-do parents in the prosperous East Coast suburb she calls “Woodcrest” (not its real name), channel their anxieties into their children’s schooling. But what it means to get an excellent education, who decides, and what success looks like are all a matter of contention—often racially tinged—between Woodcrest’s white families and those in the growing Asian immigrant community. Meanwhile, Black and Brown families and the poor are on the outside looking in.

This month on Colloquy: race and the pursuit of the American dream in suburban schools with Dr. Natasha Warikoo.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I just want to say that even if people aren't particularly interested in the sociology of education, or think they're not, they should pick up Race at the Top anyway because it's just a great read. You really have a knack for storytelling, which is where I’d love to begin our conversation. You start the book with the stories of two parents in Woodcrest: Sabrina and Mei Ling. Who are they? What are their hopes for their children? How do they exemplify the tensions between whites and Asian immigrants that are the focus of your book?

Sabrina is a white mom in the town, Woodcrest. She was upset that her son hadn't gotten into honors math. And this is at a time when, according to her son, and I think this is probably not wrong, suggested that, well, so many kids were going to these extracurricular math classes that it was hard to get into honors without having done those classes. And so, she felt this was unfair that they were being tested for honors math on material that they hadn't learned in school. So she felt her son was smart and deserved to be in honors. And now he was feeling like he was not so smart, and this felt bad.

And she kind of blamed—it was not overt, but she told me how three kids in my son's class were white and the others were Asian American. This is kind of unusual in that racial balance. The community is still predominantly white. And then she told me that there were only three kids who didn't do these extra math classes, which I assumed were the three white kids. But I don't know. And so, you know, she goes to the school, and she says, look, this is not fair. You're testing him on material he was never exposed to. Why does that determine whether he goes to honors math or not? And she got him placed up into the math class now.

And so, she blamed this sort of focus on [extracurricular math classes]. A lot of Asian immigrants were doing this, and that was creating anxiety for her son and other kids like him. And that was sort of the academic side.

Now, on the extracurricular side, her son was a very strong athlete. He played a lot of intensive sports. He was a lacrosse player, but he didn't just play lacrosse. And she told me about how in eighth grade, she was sort of looking ahead and hoping to get on to the varsity team in high school.

So he started playing club lacrosse. Now, club sports are sports outside of town sports. So you've got the usual I grew up with, like, your city ran some sports and you played whatever they offered. But club sports are—usually, there's a parent volunteer who's the coach—club sports are privately run [with] privately paid coaches. They're very expensive. And so, she put her son in a club, and they run year-round. And so, he was in lacrosse so that he could get ready to try to get on to the varsity team. So, that's Sabrina.

Mei Ling is a mom, an immigrant mom from China. And she talked about how some people blame Asian Americans for the increasing academic standards in their town. But she said, well, that's probably true, but it's similar to excellence in sports. Right? So she kind of said, well, when we see Olympians performing at a very high level, we don't criticize them. We say, like, that's great, good for you. And maybe people should do the same in academics. And so, she kind of recognized these tensions and pushback. And she said we're just focusing on different things. And this was a common theme that I heard among some Asian parents. She wanted her child to have more rigorous academic homework, while at the moment the town was talking about dialing back homework and changing their homework policy to reduce the amount of work that kids had.

So on the one hand, these two moms moved to this town—it was true of Sabrina as well—in order to kind of provide the best opportunities and educational opportunities for their children. But what they did in order to do that was very different. And what they thought was the right way to do that was very different.

So the Asian families in Woodcrest work hard, they play by the rules of the meritocracy, and they do well. Does that mean that they're accepted by the community really at a fundamental level?

Dr. Natasha Warikoo: I would say they're not fully accepted. And this is one of the things that I kept thinking about as I was doing this research. It almost feels like if we take whites as the norm, right? There, in the past, there's always been these...there have been these critiques of Black and Latin families for not emphasizing education enough, not putting their resources into education and that this was supposedly a reason that their kids were not doing well. But we know that that's not true from a lot of research. They care just as much about education as Asian Americans and whites.

And then on the flip side, now Asian Americans, when they started achieving really well, suddenly they work too hard at education and that's also—they also got a lot of pushback, and there was a lot of boundary-making around, well, that's not being a good parent. You're pushing your kids too hard academically. You are emphasizing academics too much. Your kids should have a job at Dunkin Donuts in the summer, not taking an academic class or doing research in a lab.

You know, one kind of possibility would be that white parents would see Asian Americans doing well academically and think, oh, well, maybe we should do those things if that's helping their kids academically. And that I didn't see. So very little of that.

You wrote that cultural influence when it comes to immigration is no longer a one-way street. It's not only the natives who are shaping the lives of the new arrivals. Talk about that shift that you observed.

Among scholars of immigration, we've had these debates about should we be thinking about assimilation? Is that the wrong framework? And then, of course, [sociologists] Richard Alba and Victor Nee said we should think about assimilation as, first of all, it's not normative. We're not saying it's good or bad. We're just asking whether we see declining differences between groups, and it's a two-way street. So it's the declining social distance between groups, right? There are ways in which American society, broadly speaking, has been shaped by immigration.

How does this two-way street play out in Woodcrest?

I think people are very motivated to get along. A lot of parents, white and Asian, really talk to me about appreciating the diversity of their town. They got to know people of other backgrounds, different lived experiences. So I think there was a sort of cultural awareness that was there that they experienced—that white families experienced—if we're talking about the other side of this.

And I think that Asian American families, too, obviously, when you're an immigrant, you don't really have a choice. You have to sort of get to know the culture that you've moved into. But I also think that because there were so many Asian Americans in this town—and they're still a minority but a pretty sizable number of Indian immigrants and Chinese immigrants in particular—they also had built their own kind of social life, their own social networks, ethnic organizations. There were multiple Chinese American organizations. There was one Indian American organization that was pretty longstanding in this town. And I think the school had the Diwali [holiday] off. It's one of the few school districts in the country, I think, that does that. And so, I think there was certainly this cultural awareness.

Diwali, that's the Hindu festival.

It's one of the big, big Hindu festivals. Yeah. Beautiful.

You were just kind of referencing that it's a very progressive community and people talk about the importance of diversity. You mentioned that in your book too. But then what happens when white parents feel like their kids are being outperformed by Asian children?

I think there is this tension, kind of like what I describe as Sabrina, like this, this feeling of my kids shouldn't have to go to extracurricular math to be in honors math, you know? So there's a part of me that's like, yeah, that's true. And there's a part of me that's like, well, who's to say that your child deserves to be in honors any more than anyone else? And so, this whole idea that there are certain people who deserve to be on top and others who don't I think is problematic.

But we live in this...such a sort of hierarchical world. And they're in this sort of hyper-competitive environment. And in some ways, because they're in this hyper-competitive environment and feel like they move to this town to give their children every opportunity, then suddenly it's like they got more than they bargained for by moving to this town. They start to sort of push back a little. It's never sort of overt, like, I don't like that Asians are doing this. It's more like, well, it's too much, like the kids are too stressed. We need to dial it back.

And so, one of the things that the district did, was doing while I was doing this research, was revisiting their homework policy, creating and then revisiting this homework policy. And eventually they said, okay, no homework in any of the elementary schools besides reading, independent reading. Even before I had arrived, they stopped publishing class rank; they stopped naming a valedictorian. They also did this thing that in a lot of American high schools, if you take an honors or an AP class, you get more points towards your GPA. So an A in honors counts for more than in the regular college prep. But they eliminated that because they said that encourages kids to take all these honors classes. So they're doing all these things to kind of reduce academic competition.

And on the one hand, you know, we might think, well, maybe that's a good thing. And I don't necessarily think that's a bad thing. But I also think that it's also not a coincidence that it's that at this moment when Asian Americans are outperforming whites. And I remember going to this school board meeting when they were going to talk about the homework policy, there were sort of...it was one of the many meetings about it. And the first person to get up and speak was a young white woman, very articulate, and she said I go to school—and then I don't remember exactly the activities that she had—but she said then I have this after school and then I have this and then I get home at 9:00 p.m. and I have to have dinner and then I have to do my homework. And it was this way of saying like, can you please cut back? I'm so stressed because I have all this stuff.

And the interesting thing to me at that moment was like, it kind of suddenly clicked in my mind. I was like, why is no one ever saying, well, maybe you're doing too much, right? Maybe you shouldn't be getting home at night, doing all these things that get you home at 9:00. Maybe, you know, maybe we should limit how many hours the varsity teams are allowed to occupy the children or how much extracurricular time kids should be—I mean, you know, you can't mandate what kids are doing outside of school, but there was no discussion of that.

So I think the solutions that families had to "what do we do when the kids are just overburdened" was related to ethnicity and what the parents wanted. And I think what the white parents wanted often aligned with the perspective of the school district because they had similar backgrounds. But most of the school leaders and teachers, as you know, were predominately white. It was just that their worldviews kind of aligned. They think similarly. And so that made more sense to them.

I want to come back to something that you were starting to talk about a few minutes ago, and that's the way that the success of Asian immigrants is often used as evidence for the validity of the idea of our society as a meritocracy. Can you talk about how the legacies of socioeconomic segregation and racial exclusion play out in Woodcrest?

First of all, this idea that racism is the same thing for racial groups is misguided, right? So it's not that Asian Americans never experience racial discrimination. We know from what's been happening since the start of the pandemic that Asians, particularly East Asians, have been increasingly subject to racism, and that's often violent. But the kinds of racial exclusion they experience are different. So Asian Americans might experience it more in the corporate boardroom, but if anything, in the academic setting, they may experience positive stereotypes and higher expectations than maybe they have demonstrated that warrants it, as opposed to…we know Black kids tend to experience lower expectations on their capabilities.

If you look at towns like Woodcrest, and these are sort of your traditional upper-middle-class suburbs, a lot of these towns were created as places of racial and socioeconomic exclusion, and particularly to keep upper-middle-class whites—to have them have a place away from working-class African Americans. And so we see suburbanization in the 1950s and 1960s. This is a time of school desegregation, and so you have white flight, whites who could afford to leave the city, leaving the city, moving to the suburbs so that they could...in part so their children could go to school without having to integrate with Black children.

And these towns were created and then passed laws to exclude working-class people and minimize housing lot sites. Why do we have to have a missing minimum housing lot? That doesn't make any sense to me. Or saying that you can only build single-family homes. Some of these towns protested when there were proposals to bring public transportation.

And so the interesting thing to me is towns like this were created as these bastions of privilege. And then Asian Americans come as immigrants with these high levels of skill and, you know very well, have a lot of knowledge of how to do well in particularly academic testing, in part because these are people from India and China who did well in academic testing. That's how they got to Woodcrest, right? They did well. That's what got them into graduate school in the United States. It got them this high-paying job, which allowed them to buy or rent property in this town. And so, they're almost, like, they can't be shut out of this town. And by the way, we know that Asian Americans don't experience the same kinds of racial discrimination in housing that particularly African Americans do. And so, it's easier for them to get property and they have the resources to do so. So they're able to take advantage of these systems of racial exclusion.

That is much harder for African Americans for a variety of reasons, for historical reasons. And then when you think about it, there are African American and Latino families in Woodcrest, who are professionals mostly, but very few. And you may not want to live in a town like that when there are so few people who share your background. And so, it continues to kind of perpetuate itself.

Well, that was one of the most surprising parts of your book. You have this great line about the families in Woodcrest fighting for gold versus silver or bronze, forgetting that practically everyone in town was assured of a medal. And so, the surprising part was the way in which not only whites, but also the Asian immigrant community benefit, and these are your words, “from a system designed to maintain white advantage.”

That's why I call it Race at the Top. When you're in this town, it's easy to forget that, right? Because it's so competitive and it's so, like, people are so upset that, well, I'm in this very posh town, but my child is not in honors math. But guess what? The regular math [class] is probably at a higher level than honors math in a lot of other school districts. So your town is still advantaged overall in the grand scheme of things. But it's hard to see that when you have this kind of hyper-local focus, and that is the result of this exclusion.

Last month's podcast was a conversation with Emily Bernstein, a recent alum, about the graduate student mental health crisis. And she talked more broadly about the youth mental health crisis in general. And I know that you mentioned in your book that both white and Asian immigrant parents are concerned about that for their kids. I wonder if you could a) talk about the concern, b) talk about the way that these two different groups are responding, and then c) maybe some thoughts about how to approach the issue of overstressed, over-scheduled kids [in a way] that isn't necessarily based on one culture or one group of people having the status and the influence to carry out their program.

So when I enter this town—it's funny—there's a section in the book where I talk about how I go into this town, I sort of know its reputation. And there was about to be an election for a school board. And so I go to this election forum. And I think people are going to ask about more AP tests [or] what do you do with the academic standards and sports.

And I go in and almost every question is about mental health in different kinds of ways. What are you going to do? What kinds of policies do you think are the right ones? And it kind of took me aback. And this is pre-pandemic, and people were talking about a youth mental health crisis. I think we forget that this is a crisis before the pandemic. I think that is very real.

And I think it's great that there were all of these concerns and questions and families…school leaders really trying to figure out what can we do to help our kids? And this was true of Asian American and white parents alike. So this stereotype of the tiger mom…that's just not what was going on. Asian immigrant parents, most of them also talked about this. But I talk in the book about how they have different solutions, right? They have different ideas about what the school, and they, should do.

And so I think one of the solutions that was happening was this, like, hey, let's reduce the homework. But the Asian parents were not so happy about that. I mean, I met one young man who was—he actually had only been in the US I think maybe two years. He had come from China. And he told me that he was doing a class outside of school for AP chemistry because he wasn't placed in AP, but he was still taking the class and he was going to take the AP test. And I was like, wow, that's amazing. Learning a whole language and you're going to take the college-level class. And the Asian parents basically said, kind of what Mei Ling said,when I started out right, that our kids, my kids are not doing all of these extracurriculars. And so, they have time to do extra math or take that chemistry class. And it's not stressing them out the way it might stress your kid out, who doesn't get home until 9:00.

And so basically, it was like, you do you, we're going to do us. It's all good. And it's up to the parents and the kid to make sure that they're not overextending themselves. There were a few Chinese moms who said, I really asked the school, like, can we have some intramural sports, where I don't want my child [to, or] doesn't have time to, join the varsity track team. But how about just like a running club twice a week where they can make friends, they can blow off steam. It's good for their exercise. We know it's good for your mental health, but if they have a test the next day, they don't have to go. So they wanted a sort of casual sports as a sort of solution. And also, just let families decide. Whereas I think the white families, they were different, right? They wanted to reduce the academics. It's probably not a coincidence that white families were sort of privileging the ways, the domains in which, white kids were doing better, right? They didn't want to do anything about extracurriculars. And Asian families didn't want the school to cut the academics because they were excelling in those fields. And that's what they prioritized. And I don't think that's a coincidence either.

In terms of what they should do, I think first, recognizing that there are different perspectives on what is driving mental health issues. And I think looking at some of the data from the school, it was interesting. They did a school-wide—the school administration—school-wide survey, and I looked at some of that data, and one of the questions that [was] asked was how much pressure do you feel from your parents to get good grades in school? And so there's this stereotype that the Asian parents are pressuring their kids, and interestingly, the group that reported the highest level by far of parental pressure was the Black kids.

Now, most of the Black kids in the school were actually not from the town. They were part of a busing program from the urban center. The district had this program where kids could come in, [starting] from kindergarten, to the schools in the district, and there was a bus provided for them. And so anyway, I just think that it's important to understand where the pressure is coming from, where kids are feeling it from. And in some ways, it's like what you really need is to diversify the town, right? You need more class integration. You need to not be in this place where you have a concentration of adults who all—a majority have graduate degrees, not just college degrees.

Only one in three American adults has a bachelor's degree. But over half of the adults in this town have a graduate degree, and not just a graduate degree. They're often from very elite places, and they think that's normal. It's just what everybody does, to go to a college where the acceptance rate is below 20 percent. That's not normal. Most kids don't get into those. Most don't even apply to those places. A majority of college students go to open-access schools in this country. And so, I think the whole—the policies have to change to make this town less exclusive. So it's hard to say at the school level, what should we do? But I also think a little bit more understanding of, well, what are parents’ priorities? And let's not assume that others don't care about mental health.

So, to end at the beginning, in some ways, there's this line you have about us living in an age of anxiety. Take the thousand-foot view and talk about how you see the larger problems rooted in the structure of our country, and in our society, manifest in the behavior of parents around their children's education. And this is by way of asking you, really, if we can make substantial improvements in the equity of our educational systems if we don't address the larger issues.

Education can't do everything. And I think in the United States we just assume it's okay to be unequal as long as we have educational equity. But it's really hard to provide an equal education when our society is so hierarchical in so many ways.

In terms of the income distribution, the difference between what people at the top and the people at the bottom earn, in terms of social supports—we have so few social supports given the wealth of this country in terms of economic and racial segregation of neighborhoods, which is how schools get funded and where kids go to school. That's what I'm talking about. And I think community colleges do amazing work, but the resources that they have and what they're able to do compared to what private universities like Harvard, like Tufts are able to do is just a world of difference. Higher education doesn't need to be so hierarchical. It's much flatter in places like Canada and much of Europe.

And so that troubles me. You know, I think when we're sort of...we're so committed to this idea of meritocracy and of judging people and ranking people in ways that I think are problematic because everybody deserves a high-quality education. Everybody deserves a basic standard of living. Everybody deserves basic, high-quality K-12 education and higher education.

The Colloquy podcast is a conversation with scholars and thinkers from Harvard's PhD community on some of the most pressing challenges of our time—from global health to climate change, growth and development, the future of AI, and many others.

About the Show

Produced by GSAS Communications in collaboration with Harvard's Media Production Center, the Colloquy podcast continues and adds to the conversations found in Colloquy magazine. New episodes drop each month during the fall and spring terms.

Talk to Us

Have a comment or suggestion for a future episode of Colloquy? Drop us a line at gsaspod@fas.harvard.edu. And if you enjoy the program, please be sure to rate it on your preferred podcast platform so that others may find it as well.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast