A Better Way to Vote

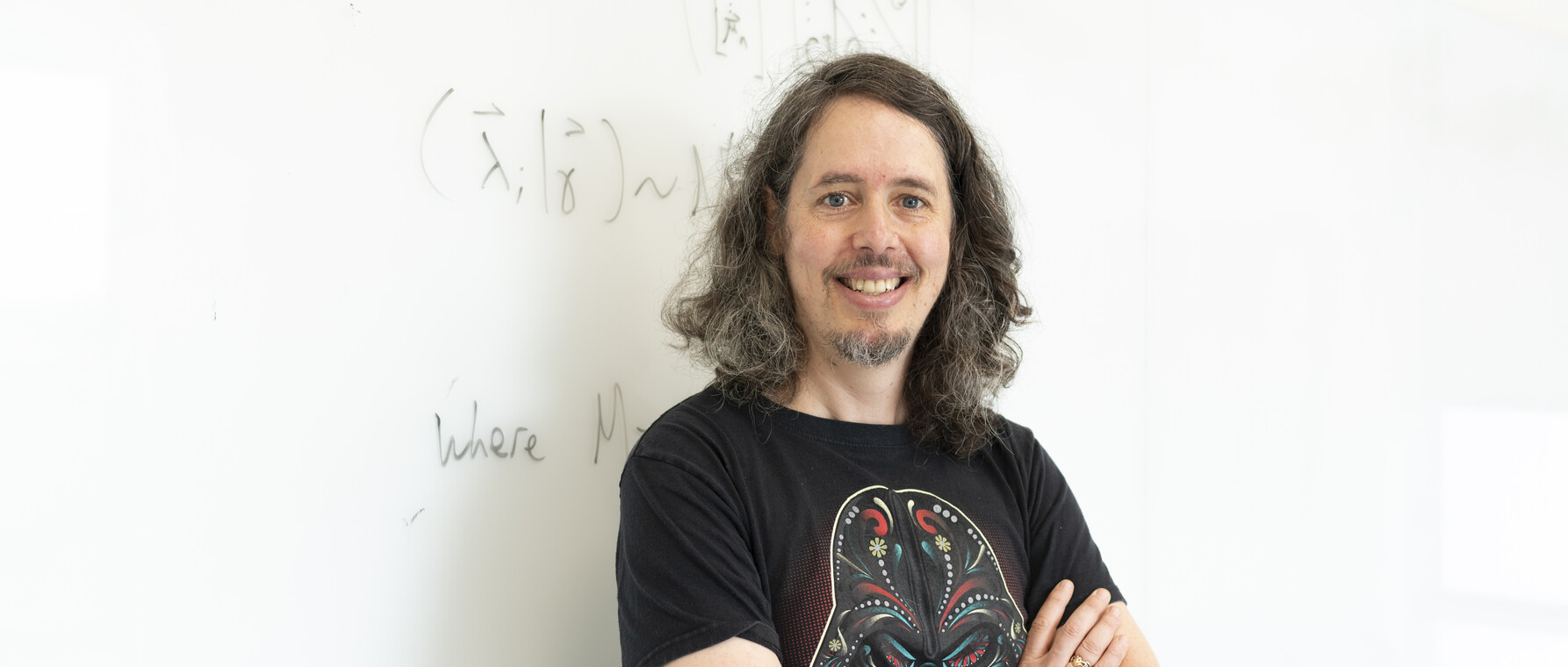

How Jameson Arnold Quinn brings together statistics and voting theory

In 2015, the World Science Fiction Society faced a problem with the voting method for the Hugo Awards, a set of literary awards it presents annually for the best science fiction or fantasy works of the previous year. A subgroup of alt-right sci-fi fans and writers were dissatisfied with how the awards were becoming “too politically correct” and organized themselves into a voting bloc that ended up monopolizing the nominations. Enraged fans ended up voting “no award” in categories with nominees manipulated by this rogue group, resulting in an unprecedented seven categories where no award was given.

At this juncture, Jameson Arnold Quinn, a PhD candidate in statistics, stepped in and offered his expertise in voting systems. “I was involved enough in nerd culture to be aware when the problem happened. I already had the theory to create a voting method that would work for them, so I developed that, put myself forward, and helped get it passed at the business meeting for ratification.” Quinn’s voting method is still being used for the Hugo Awards today.

An Unusual Path

After earning a bachelor’s degree in cognitive science from Oberlin College, Quinn worked as a programmer. However, his abiding interest in voting theory motivated him to apply to graduate school. While he mostly considered degrees in political science, he decided to do something unconventional and study statistics instead. “I’m thankful I did,” he says. “It’s good to come at your main interest from an unusual path. That way, you’ll be able to find things that other people wouldn’t.”

After the 2000 presidential election, many commentators speculated that Ralph Nader’s candidacy took votes away from Al Gore and paved the way for George W. Bush to assume the presidency. The election's outcome convinced Quinn that the voting method in the United States is inadequate when dealing with multi-candidate elections. Voting theory is usually considered in terms of axioms that place strict requirements upon an election procedure. But it’s impossible to create a voting method that meets all reasonable requirements. For Quinn, statistics provides a different way of thinking about how people vote and can be used to develop an alternate model of voting behavior.

In his research, Quinn uses statistical techniques to discover patterns that can be gleaned from existing data about candidates, as well as data about voter racial demographics. His goal is to develop a method that will be more useful in voting rights lawsuits. He cites an example from Lowell, Massachusetts, where the plaintiff consists of a group of Asians and Latin Americans. Quinn and his colleagues ask whether these two groups have common interests and tend to vote together; insofar as they do, they become large enough to have the right to have their own representative; a member of the city council whom they’ve helped elect. “We need a method that can deal with more than two groups, more than two candidates, and/or more than one choice per voter, preferably all at the same time,” Quinn explains. “The method I’m developing can do this more flexibly.”

In Quinn’s opinion, voting theory has been neglected because it falls between political science and a subfield of math, and as a result, its statistical component is often overlooked. Some research in the area is being conducted by a community of amateur voting theorists, which hasn’t penetrated into the academic literature. “I want to bring their work into the conversation because the academy is and has always been the canon of knowledge,” he says. “If it’s not in the scientific peer-reviewed literature, it doesn’t exist.”

Changing the Way We Vote

In the early 2000s, Quinn joined an online community that grew to become the Center for Election Science, a nonpartisan non-profit that studies and advances better voting methods, especially in the United States. He now sits on the organization’s board of directors. “The interesting thing about voting theory is that, mathematically speaking, it’s very simple,” he explains. “So, it’s completely possible for an amateur to understand and push the frontier of knowledge, much more so than other mathematical fields.”

The Center advocates for approval voting over the choose-one system currently in place. “The difference is simple,” Quinn states. “In the US, you review the ballot and choose one candidate. In approval voting, you can choose one or more.” This simple change would lessen some of the negative effects of the current system. But those who disagree often cite that democracy in America is based on “one person, one vote,” inferring that those allowed to vote for more than one person have more than one vote. Quinn believes this isn’t exactly true.

“Approval voting is also based on equal voting power,” he explains. “Other reforms exist that could improve single-winner voting, and you can have reasonable arguments about which voting method is better, but everyone agrees that all of them are preferable to the current system.” Through their advocacy, the Center for Election Science helped an approval voting initiative pass in Fargo, North Dakota.

Looking Forward

While the election system came under increased public scrutiny after the 2016 election, that renewed focus didn’t change the fundamental questions Quinn has been asking for years. “Gerrymandering is the more important concern,” he warns. In 2010, members of the Republican and Democratic parties used new geographic information system mapping and surveying technology to create and manipulate congressional districts, bringing Gerrymandering back to the forefront of political debate. Quinn explains that the legality of those new district maps are still being debated in court.

Though hurdles to more effective voting systems do exist, Quinn remains optimistic about the future. “There are big problems with US politics and I can trace these problems back to structural issues with our voting method,” he says. “That said, we are in a position to actually fix them. If we do this right, we can really start to make real change.”

Photo by Molly Akin

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast