Sound Mind

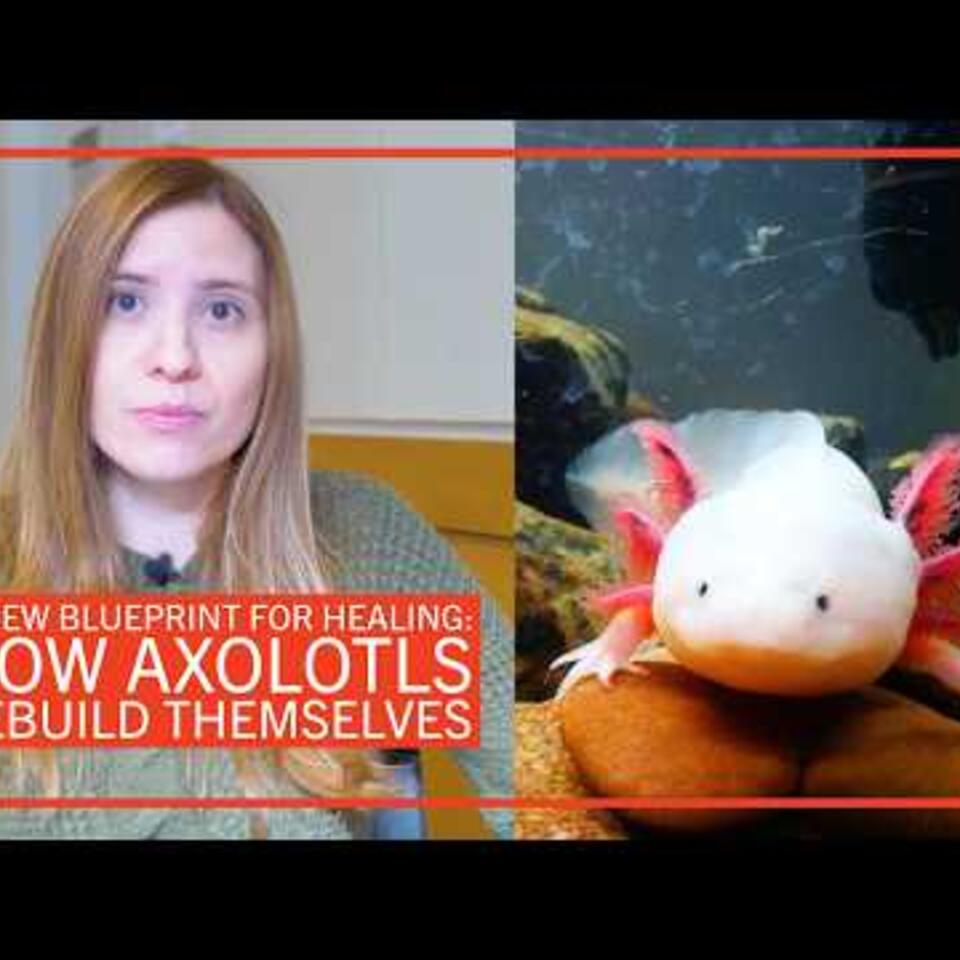

Aaron Berkowitz’s effort to improve neurological care in some of the world’s most impoverished regions was shaped by his study of musicology at Harvard

“I present to you patient Janel, a 23-year-old male student with no prior medical history, born and currently living in Savanette, presenting for evaluation of headaches evolving over several months, a sense of vertigo when he stands, and difficulty walking.” So began an email that would intertwine the lives of Dr. Martineau Louine, the patient he described, and me.

—Aaron Berkowitz, One by One by One: Making a Small Difference Amid a Billion Problems

In his 2020 book, One by One by One, Aaron Berkowitz reflects on life as a young physician working in Haiti and following in the footsteps of his teacher and role model Paul Farmer, PhD ’90. A neurologist, Berkowitz first traveled in 2012 to the Caribbean nation—one of the poorest in the world—at the suggestion of his colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He was asked to teach in a country where there was only one other doctor in his field.

During his time in Haiti, Berkowitz often had to improvise, both with his treatments and his pedagogy. Fortunately, improvisation was the subject of his dissertation as a PhD student in music at the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS), from which he graduated in 2009. It’s also the story of his career—from Haiti to director of global neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital to clinician-educator at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) today.

The Improvising Mind

Berkowitz grew up with a love of classical music, especially the works of piano romantics like Chopin and Rachmaninoff. He also had a passion for medicine. So, after majoring in both music and biology as an undergraduate, he enrolled at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. By his third year, however, the high pressure, long hours, and little sleep began to wear him down. “I decided to get out,” Berkowitz says. “I thought I could study musicology and become a music professor at a small liberal arts college. The lifestyle of a graduate student in the humanities would be a welcome change from medical school.”

In 2003, Berkowitz came to Harvard to pursue a PhD with a focus on ethnomusicology. Combining manuscript studies with ethnography, anthropology, and neuroscience, he studied brain activity among people from different musical traditions who learn to improvise or teach improvisation. His dissertation yielded his book, The Improvising Mind: Cognition and Creativity in the Musical Moment, in which Berkowitz defined musical improvisation as “the spontaneous rule-based combination of elements to create novel sequences that are appropriate for a given moment in a given context.”

Most of the neuroscience literature focused at that time on the perception of music rather than on its production. “There are essentially two basic questions in music cognition,” says Berkowitz. “First, what parts of the brain are involved and how do they interact when people listen to or perform music? Second, what can studying music tell us about the brain?”

When music is heard or played, the brain calls on many more general cognitive processes—for example, perceiving patterns in sounds or converting visual information to auditory or motor information. To explore this phenomenon further, in 2009 Berkowitz teamed up with Daniel Ansari, a neuroscientist at the University of Western Ontario, to design an experiment that would attempt to isolate the brain regions responsible for the creativity underlying musical improvisation.

The duo had 12 classically trained pianists in their 20s perform a series of 4 musical tasks while inside a functional magnetic resonance imaging machine. The study participants played a small, plastic piano-like keyboard that had five keys.

Berkowitz and Ansari found three regions of the brain that were activated during all tasks that involved improvisation: the anterior cingulate, which is involved in most cognitive tasks, including decision-making; the dorsal premotor cortex, which acts as a type of command center for executing movements; and the inferior frontal gyrus/ventral premotor cortex, which has long been known as an area involved in language production.

“During a task like improvisation, a musician is flooded with multiple choices for what to play at any given moment,” Berkowitz says. “So it made sense that the anterior cingulate region lit up during improvisation. We expected the dorsal premotor cortex to be involved, too, because it was already active during the playing of memorized melodies. But we were the first to show that the inferior frontal gyrus/ventral premotor cortex activates when people create music.”

There are essentially two basic questions in music cognition. First, what parts of the brain are involved and how do they interact when people listen to or perform music? Second, what can studying music tell us about the brain?

—Aaron Berkowitz

Even as he wrote the dissertation, the path of Berkowitz’s own life and work was changing once again. At the urging of his faculty advisor Professor Kay Shelemay, he enrolled in a class co-taught by anthropology professor Arthur Kleinman, AM ’74, and Partners in Health (PIH) cofounders Paul Farmer and Jim Yong Kim, PhD ’93. (Kim later went on to lead Dartmouth College and the World Bank.) The course focused on PIH’s work in Rwanda, Haiti, and other places around the globe plagued by inadequate access to health care and extreme poverty.

“I was just blown away,” Berkowitz says. “I had never heard of ‘global health’ or ‘medical anthropology.’ For me, medicine had been biochemistry in the classroom and spending long hours in the operating room. I went back to Johns Hopkins for the last year of medical school after I finished my PhD in music. Then, I applied for a residency in neurology with the idea of doing work in global health and health equity inspired by Paul Farmer’s work. That’s what led me to Haiti.”

A Partner in Health

Paul Farmer described the chief tension of PIH’s work as the struggle to serve those in front of you while simultaneously working to improve public health in the long term. In One by One by One, Berkowitz writes that he grappled with that challenge in Haiti—exemplified by the case of Dr. Louine’s patient, Janel.

“With Janel right in front of us, it actually didn’t seem like that much of a tension to me,” he wrote. “I knew I couldn’t come up with a sustainable, cost-effective solution that would solve enormous problems like global poverty and inequitable access to modern health care—I would have to leave that to the Paul Farmers of the world. But as a doctor, couldn’t I try to help this one patient?”

Janel was diagnosed with the largest brain tumor Berkowitz had ever seen. Because the surgery would have been impossible in Haiti, the young neurologist flew his patient back to Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Michelle Morse, chief medical officer of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, was part of the team that treated Janel in Boston. She calls Berkowitz a visionary and a brilliant clinician with a passion for helping those the world has left behind.

“Aaron believes in the need to work in proximity to marginalized communities in order to fight structural violence,” she says. “Janel is a patient who epitomized that struggle. We worked for years to push for the best care possible, and in Janel’s case that required a medical evacuation.”

Aaron believes in the need to work in proximity to marginalized communities in order to fight structural violence. Janel is a patient who epitomized that struggle.

—Dr. Michelle Morse

Janel was young and there was hope he might respond well to treatment—perhaps recovering and returning to school. He needed five surgeries, repeated hospitalization, and long-term rehabilitation, but he was walking, talking, eating, and even singing by the time Berkowitz left Haiti. Sadly, Berkowitz hasn’t seen his former patient in several years due to the strife that has gripped the country.

“In 2021, the president of Haiti was assassinated, and it has become extremely violent there,” he says. “My colleagues at Partners in Health have said they don’t feel it’s safe for outside travelers, given the security risks. They tell me that Janel is still doing as he was at the end of the book. It’s not the huge save we were hoping for, but he’s still alive after what was likely to have been a deadly condition, and we’re grateful for the small victories.” (Berkowitz continues to support his colleagues in Haiti through online teaching and consultation and hopes to return when it is safe to do so.)

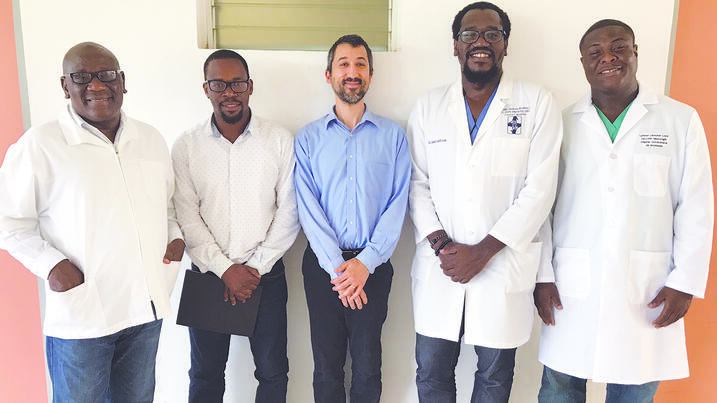

Although Berkowitz and colleagues in Boston were able to provide lifesaving treatment for Janel’s brain tumor, it couldn’t have been replicated at scale. So, improvising once more, Berkowitz taught neurology in Haiti, which previously had almost no specialists in the field. He began by teaching groups of primary care doctors until his Haitian colleagues suggested the country would be better off if they trained even a small group of experts who could start their own neurology program.

Berkowitz encountered many challenges teaching in a setting very different than the one he was used to in the US. “First of all, the epidemiology of disease is different,” he says. “There’s lots of tuberculosis in Haiti whereas I saw none in residency in Boston.” To make matters worse, the country experienced an outbreak of the Zika virus in 2016 when Berkowitz had barely finished training its first neurology graduate, Dr. Francois Roosevelt. When cases of Zika-related neurologic disease started to proliferate, however, his former pupil began to shine.

“Francois diagnosed Haiti’s first cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome due to Zika infection,” Berkowitz says. “He even published a report on this, which led to a scholarship to the American Academy of Neurology annual meeting in Boston where he was the first Haitian national to give a lecture presenting his work. We worked together to best integrate neurology education and care into the country’s medical system.”

Deep Listening

Today, Berkowitz continues to uphold his commitment to teaching neurology while serving patients as a professor at UCSF. His roles there are varied but interconnected—from being a neurohospitalist and a general neurologist to his work as a clinician-educator at the San Francisco Veteran’s Administration Medical Center and San Francisco General Hospital. “It’s great not only to be part of a huge university medical system,” Berkowitz says, “but also to be serving two very uniquely underserved populations—the veteran population and the underserved population of urban San Francisco.”

His previous experience as director of global neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital continues to inform his work, particularly his emphasis on improving access to neurologic care. But Berkowitz’s influence extends beyond the classroom and the hospital ward. In recent years, he has taken what he learned in Haiti to the Navajo Nation and the international humanitarian organization Doctors Without Borders, which provides lifesaving medical care around the world to those who need it most.

Berkowitz engages with the wider neurology community through his role on the editorial board of the journal Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. In addition to One by One and The Improvising Mind, he has contributed to the Oxford Manual of Humanitarian Medicine, penning the neurology chapter, and has authored the neurology textbook Clinical Neurology and Neuroanatomy: A Localization-Based Approach. Berkowitz’s many awards and honors include the Mridha Spirit of Neurology Humanitarian Award from the American Brain Foundation in 2018 and the Viste Patient Advocate of the Year Award from the American Academy of Neurology in 2019.

When asked how his Harvard Griffin GSAS experience served him in Haiti, Berkowitz says the core of ethnomusicology is deep listening, a skill that he has taken with him to medical practice at the bedside. “I wasn’t studying the music of Haiti, but my PhD work trained me to be able to try to truly listen to colleagues and patients in different contexts.”

And so, like the romantic composers he adored as a child, Berkowitz has uniquely orchestrated the different aspects of his career, seamlessly transitioning between different movements. Each phase, from Harvard to Haiti and now UCSF, resonates with the core principles of his life’s work—serving his patients and democratizing neurologic care and education. Inspiring and powerful, Berkowitz’s story is a testament to the ability of an individual player to harmonize with different voices in very different environments to make a difference in the world.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast