Slavery on Her Mind

Harvard Griffin GSAS Voices: Chandra Manning, PhD ’02

Chandra Manning is a historian at Georgetown University where she studies the American Civil War, slavery, and emancipation. She talks about the prominence of slavery in the minds of ordinary 19th-century Americans, the way that formerly enslaved people helped reshape the relationship between the United States government and its citizens, and how an academic mishap during her time at Harvard Griffin GSAS turned into a lesson on the power of effective mentorship.

The Role of Refugees

I am a historian interested in how the development of slavery and the United States affected each other. The question of the relationship between ordinary Americans and the creation, maintenance, and end of slavery has been the crux of my career.

In my research, I’ve discovered that slavery was very much on the minds of ordinary Americans in the 19th century. For example, both Union and Confederate soldiers during the Civil War discussed slavery with each other even if they weren’t enslavers themselves. Northerners with limited exposure to slavery talked about it, as did non-slaveholding Southerners. I was surprised by the pervasiveness of slavery in the mental spaces of ordinary people, whether enslaved or unenslaved, Northerner or Southerner.

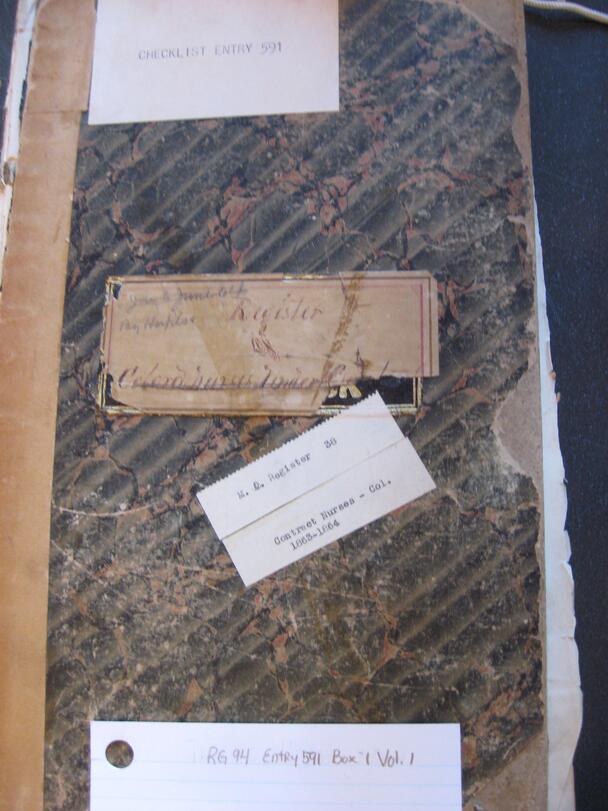

Another piece of history I uncovered that has stuck out to me was the interaction between the Union Army and formerly enslaved people who fled the Confederacy. In the years before the Civil War, the army was not an abolitionist institution and was often on the side of slaveholders. Despite this long-standing relationship, nearly half a million formally enslaved people ran to the Union Army and spent the war in what were essentially refugee camps. These people directly helped the war effort by working as nurses, laborers, cooks, and spies. Often, they knew the local area better than the Union soldiers. I believe that those interactions fundamentally changed the relationship between the central government and the individual person or, in other words, our expectations of who can be a US citizen and what US citizenship means.

Before the war, citizenship was understood quite differently than how we think of it today. For one thing, state governments—not the federal government—decided who could be a citizen, and many states used fixed characteristics including race. Another difference is that individuals might enjoy an array of individual rights, but citizenship was not what protected those rights. So most ordinary people would not expect the federal government to have a direct obligation to protect their rights. Certainly, the federal government had no sense of obligation to enslaved people.

Then, people fleeing slavery directly aided the day-to-day Union war effort on the ground. In return, they looked for protection from the army and the government that the army was fighting to save. Suddenly, a Union provost marshal representing the US government might find himself confronted with an enslaver demanding the return of a woman who had run away from him and was now in a camp nursing for the Union Army. In that scenario, the provost marshal did feel an obligation to protect the woman from a slaveholder.

That dynamic recurred over and over again wherever the Union Army went throughout the course of the war, and it built a sense that the US government owed some level of basic rights protection directly to individuals who exhibited allegiance to it. Today, we owe our expectation that the federal government has a direct obligation to us and to the protection of our individual rights in very large measure to the actions of formerly enslaved people in Civil War refugee camps.

The Second Kind

At Harvard Griffin GSAS, my mentor was the late William Gienapp. He was a terrific advisor, but before graduate school, I was unfamiliar with his work. In the very first paper I wrote for him, I ended up taking a position that was directly contrary to the one he laid out in the book he was most known for. I had no idea. I found out when I was talking to a graduate school friend about my paper, and they turned to me with this ashen expression and told me what I had done. I went to the library, checked out the book, read it, and just thought, “Oh no.”

I went to talk to him very sheepishly. I said I was sorry. He said that he admired my courage and told me there were two kinds of professors: those who want you to think like them, and those who want you to think. “I am the second kind,” he told me. He proved it over and over again during the years I worked with him.

As for my paper, he was right, not me. Over the course of my research, I took positions sometimes that he was wary of, but he always let me go where the sources took me. Throughout my career since then, I have striven to be that “second kind” of professor—one who wants their students to think.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast