Serendipity In Science

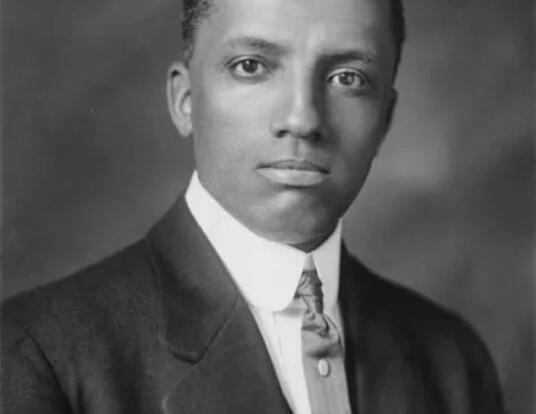

2024 Centennial Medalist Joan Steitz, PhD ’68

"It's about time," said Nancy Hopkins, PhD ’71, when told Joan Steitz had been nominated for the Centennial Medal. “She should have won it years ago.”

Hopkins, the Amgen Professor of Biology Emerita at MIT, was an undergraduate at Harvard when she first became aware of Steitz, then a graduate student. “I was kind of in awe of her,” Hopkins recalls. “At the time, people were asking, ‘Can women be great scientists?’ and it wasn’t long before Joan became one of the first to clearly show that, boy, could they ever.”

The work that so impressed Hopkins—and the rest of the scientific world—was on ribonucleic acid (RNA), which recently had a starring role in corralling the COVID-19 pandemic. Steitz’s many discoveries regarding the molecule helped to clarify how proteins form in the body and laid the groundwork for the development of targeted therapeutics, particularly for cancer, autoimmune conditions, and infectious and neurodegenerative diseases.

But she almost didn’t become a scientist. Now the Sterling Professor of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry at Yale and an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, she says she initially intended to go to Harvard Medical School (HMS) to be a physician. “I knew a couple of women doctors,” she says, “but I had never seen a woman professor of science or head of a lab and didn’t think it was conceivable.”

The summer before she was to start at HMS, she got a job in the University of Minnesota lab of the cell biologist Joseph Gall, who later went on to Yale and became known as a pioneer of cell biology. In Gall’s lab, Steitz worked on tetrahymena, a type of single-celled organism that has a nucleus enclosed within membranes. It was there that she decided bench science was her true calling.

I was kind of in awe of her. At the time, people were asking, 'Can women be great scientists?' And it wasn't long before Joan became one of the first to clearly show that, boy, could they ever.

— Nancy Hopkins, PhD ’71, Amgen Professor of Biology Emerita, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

It was her second turn at lab work; under the work-study program at Antioch College, Steitz had spent several terms working in the lab of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) biophysicist Alexander Rich, where she learned about the molecular building block deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and met James Watson, its co-discoverer. After doing her PhD work with Watson at Harvard, she got a postdoctoral fellowship in Cambridge, England, with his collaborator, Francis Crick, and the molecular biologist Sidney Brenner. “Crick suggested I find a project to do in the library,” Steitz says. “But I wanted to do bench work. So I went around and talked to the other postdoctoral fellows, and found out about an exciting but challenging project—to figure out whether special signals helped bind ribosomes to messenger RNA. None of the male fellows would take this on because they needed something to show when they went back to the US, but as a woman, I figured I’d never have a job like that anyway. And it turned into my whole life in science.”

“Joan predicted and proved how RNA-RNA interactions worked. These interactions play a crucial role in biological processes like protein production and gene regulation, so this set off the whole field,” says Yale biochemist Susan Baserga, a postdoctoral fellow in Steitz’s lab. “Her mind was always turning and thinking about the next big question. So her work really changed the world by showing how important RNA is to being human.”

Another way Steitz changed the world, Baserga points out, is by being an outspoken advocate for women in science. “She has tried to give the same opportunities she had to as many women as she could reach,” Baserga says.

It wasn’t only her mentees who took something away from those interactions. “It’s almost as much fun to share the joy of discovery with a younger colleague as to make the discovery yourself,” says Steitz. “I got very lucky that I ended up in this place and that place and meeting this person and doing that. Serendipity is very important in science. You have to keep your eyes open for opportunities.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast