The Secret Seeker

Elizabethans used ciphers to preserve their agency—and to speak to us through the ages

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

GSAS student Vanessa Braganza had been at the massive 2019 Firsts Rare Book Fair in London’s Battersea Park for hours. She was hungry. She was tired. Her feet were sore. She turned yet another corner in the labyrinthine layout of the fair just trying to find the exit, and there it was: the “impossible object.”

“It was like the whole city of London just slowed down around me,” she remembers. “I had this jolt of electricity running through my veins.”

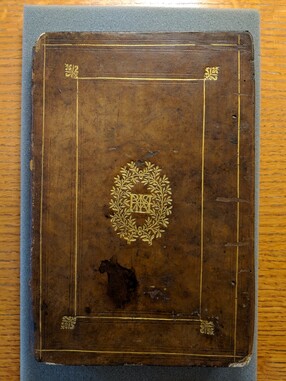

The spark was a copy of a book from the personal library of the Lady Mary Wroth, the first female English novelist, who lived during the 17th century. The library’s contents were long thought lost after Wroth’s residence burned down in 1836 but Braganza recognized the volume from the encoded monogram on the cover, entwined letters that referred to Wroth’s extramarital affair with her cousin, William Herbert, the 3rd Earl of Pembroke. (The book was acquired, thanks to her, by Harvard’s Houghton Library.)

Braganza’s encounter with the ciphered monogram inspired first curiosity and then a sort of scholarly obsession with cryptography. In her 2022 Harvard Horizons project, “The Secret-Seekers: Renaissance Writers and the Birth of Code,” the PhD student in English seeks not only to reveal the ways that ciphers shaped early modern English literature but also to inspire both literary critics and general readers to look more closely at texts and question what we think we know.

A Lover’s Gift

Although literature—like all art—begins as an act of expression, it is also inherently secretive, according to Braganza’s advisor, Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Professor of English James Simpson.

“So many of the great formal procedures of literature are effectively in code,” says Simpson. “For instance, allegory essentially means saying one thing and meaning another. Allegory’s close cousin irony is saying one thing and meaning its opposite. To write in actual code is a more extreme version of standard literary practice.”

Coding of the kind Braganza studies was a routine source of safety for monarchs, courtiers, and even authors—and pleasure for readers who felt part of the ‘in crowd’—particularly during the schismatic Protestant Reformation of the 16th and 17th centuries.

“The late medieval and early modern European world is one in which speech is dangerous, for religious, political, and personal reasons,” Simpson says. “Writers in especially sensitive situations of this kind resort to allegory, or perhaps even code, to create more intimate audiences ‘in the know.’”

Wroth was notorious during her time for The Countess of Montgomery’s Urania, the first English novel written by a woman. When disentangled, the intertwined letters of the monogram that appeared on the cover of the volume Braganza discovered at the book fair spell out the name of Urania’s two lovers, Pamphilia and Amphilanthus, based on Wroth and Herbert.

“The Urania’s plotline boils down to a story of an extramarital affair that Wroth had with her cousin,” Braganza says. “To go along with this fictionalization of the real, she created a ciphered monogram. Before I discovered this new volume from Wroth’s library, which is a biography of the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great, the monogram was known to appear only on the cover of a play that Wroth wrote for Herbert and gave him as a lover's gift.”

The late medieval and early modern European world is one in which speech is dangerous, for religious, political, and personal reasons. Writers in especially sensitive situations of this kind resort to allegory, or perhaps even code, to create more intimate audiences ‘in the know.’

–James Simpson

Cryptography and literature intersect with Wroth because the reader can’t fully be conscious of the meanings in her work without understanding the monogram. This realization led Braganza to wonder if ciphers had infused the literary imagination in other ways.

“I found that the history of cryptography intersects with magic,” she says. “A whole genre of cryptographic manual starting in the late 15th century are actually disguised as spellbooks. They’re capitalizing on the idea that the naïve reader will think they’re reading spells, but if you look closely there are hidden messages in the spells. This practice of hiding messages in plain sight in another text was called steganography.”

Braganza says that this distinction between “spurious knowledge” like fake spells and “real knowledge” of embedded meanings permeates some of English literature’s most influential works. “You find it in Milton's Paradise Lost, Shakespeare's The Tempest and Macbeth, and Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus.”

Her research illuminates the influence of ciphers on the life and letters of at least one other important figure in English history as well—one who predates Wroth: Mary, Queen of Scots.

Secrecy as Agency

The life—and death—of Mary Stuart is a story we think we know, if only from its many depictions on film; Katherine Hepburn, Vanessa Redgrave, and, most recently, Saoirse Ronan have all portrayed the doomed Stuart queen first imprisoned and then executed by her royal rival Elizabeth. But her letters, written in code, and her poetry upend our notions of Mary as a woman with no agency, swept under by a powerful leader and the currents of history.

“Popular depictions tend to see Mary as passive, beautiful, and unfortunate,” Braganza says. “But even when she is under house arrest, her ambition has not dwindled. It comes out in these ciphered letters that, by God, she is doing everything she can not only to get out but also to take the throne of England from Elizabeth. She’s going to go down fighting.”

Ironically, the secrecy that enabled Mary’s agency is one reason why her authentic voice is often lost in the way we remember her—and why many of her letters remain encoded. Having to decipher Mary’s works simply to read them is a barrier for historians and literary scholars. “And because of the absence of her written voice in the historical record, there's a tendency to see her more as a tragic figure rather than as an actor or agent,” Braganza says. “The result of that impression of passivity that starts with her loss of voice is further loss of voice.”

Braganza sees a different—and more fundamental—kind of agency in the little-known poems of Mary, Queen of Scots than she does in the letters. It’s an insistence on raising her voice—on simply existing—even in the face of annihilation. Braganza points to a passage from a poem Mary wrote in the margin of one of her prayer books during the last year of her life: “I am at once a body deprived of a heart . . . No longer, oh enemies, be envious / Of one who no longer has the disposition for greatness.” (Translated from French.)

It comes out in these ciphered letters that, by God, [Mary, Queen of Scots] is doing everything she can not only to get out but also to take the throne of England from Elizabeth. She’s going to go down fighting.

–Vanessa Braganza

“At first it seems like the opposite of agency,” Braganza explains. “She’s hollowed out. But when everything has been taken from you—even your ability to communicate with the outside world—there is a kind of agency in articulating yourself. It’s the dignity of utterance that says, ‘my existence matters'. . . or even just, ‘I am.’”

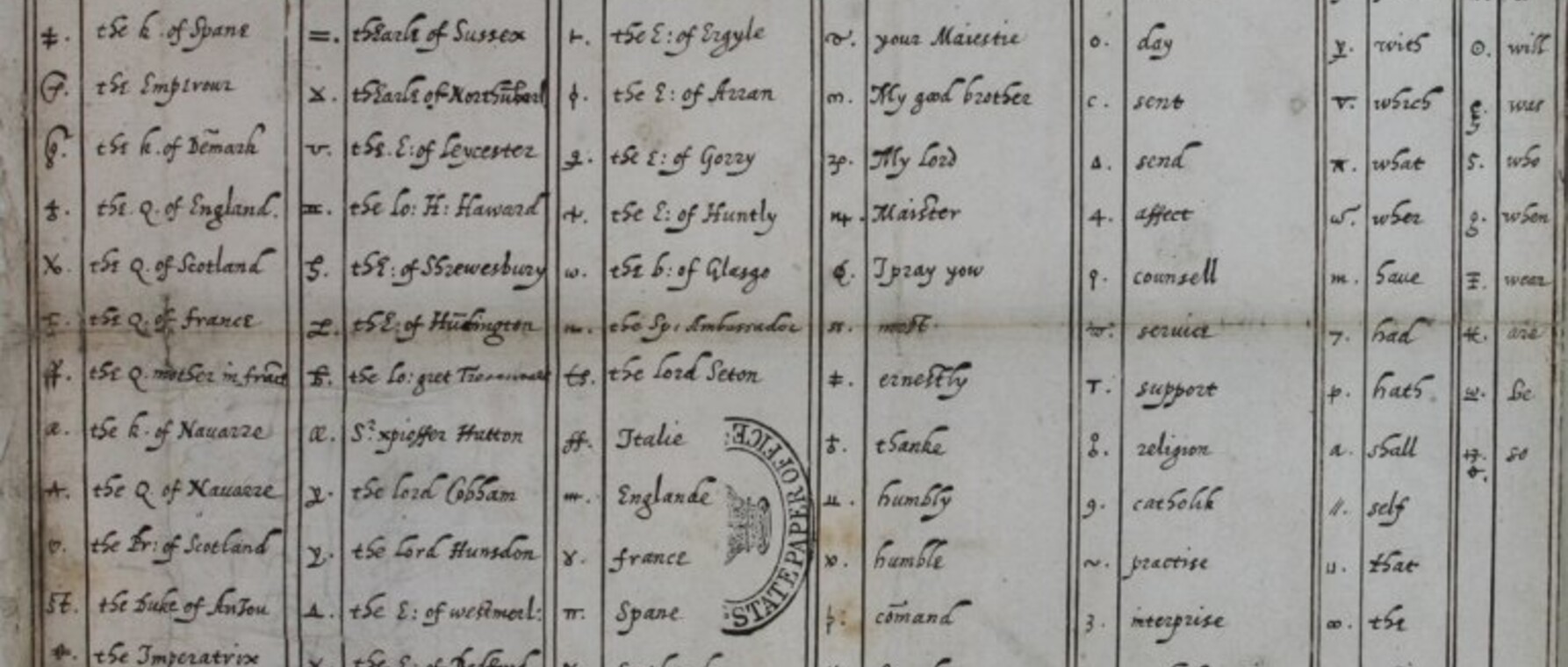

Sadly, the proximate cause of Mary’s death was the failure of her code. She neglected to refresh the symbols in her cipher, so when her correspondence with Anthony Babington, the man plotting Elizabeth’s assassination, fell into the hands of the English Queen’s spies, Mary’s collaboration was revealed.

“Mary’s use of a simple substitution cipher proved fatal,” Braganza says. “All of her correspondence was intercepted and decoded by Elizabeth’s network of spies—particularly Thomas Phelippes, a Cambridge linguist who was probably the best codebreaker in England. She was condemned and executed.”

Weird Sisters and Ghosts

Harvard’s John Cogan University Professor of the Humanities Stephen Greenblatt, who also advises Braganza’s dissertation research, says that scholars have typically not explored that which is deliberately hidden because there is so much of interest that is not. “What is not kept secret in early modern literature—what is manifest in poems like the Epithalamion or in plays like The Tempest—is already sufficiently complex and challenging to occupy most of our time,” he says. “To try to pick up clues in order to discover what was deliberately hidden is exceedingly difficult.”

Greenblatt says that Braganza’s work helps us better understand how early modern writers played a “game of expressive daring” at a time of danger and censorship.

“Take the moment in the first act of Macbeth, when the Weird Sisters are chanting what sounds like a mad nursery rhyme,” he says:

Thrice to thine, and thrice to mine,

And thrice again to make up nine.

Peace, the charm’s wound up.

“That word ‘Peace’ is not a pleasant appeal for a gentle accord; it is a call for the silence of concealment. Evidently, something has been made and hidden. What on earth is going on here? Vanessa’s work may give us the answer and expose at least more of what has been hidden.”

Braganza says that she wants her work to inspire scholars to look again with fresh eyes at texts they think they know. “It can be as simple as looking beyond your expectations,” she says. For a more general audience, she hopes her work can help non-specialists appreciate the way that historical distance can collapse and people long dead can come alive.

“My favorite moments in my work are when a piece of historical evidence makes someone's way of thinking and feeling completely legible,” says Braganza. “That doesn’t mean ‘fiction-making.’ There are pieces of historical evidence that are incredibly incisive and can bring the person to you as though they're sitting across from you. That's a powerful experience and conducive to non-specialists learning history and finding it interesting—when you find yourself nose to nose with ghosts.”

Portrait by Stu Rosner; other photos courtesy of Vanessa Braganza, Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard University, and WikiCommons

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast