A Scholar and a Practitioner

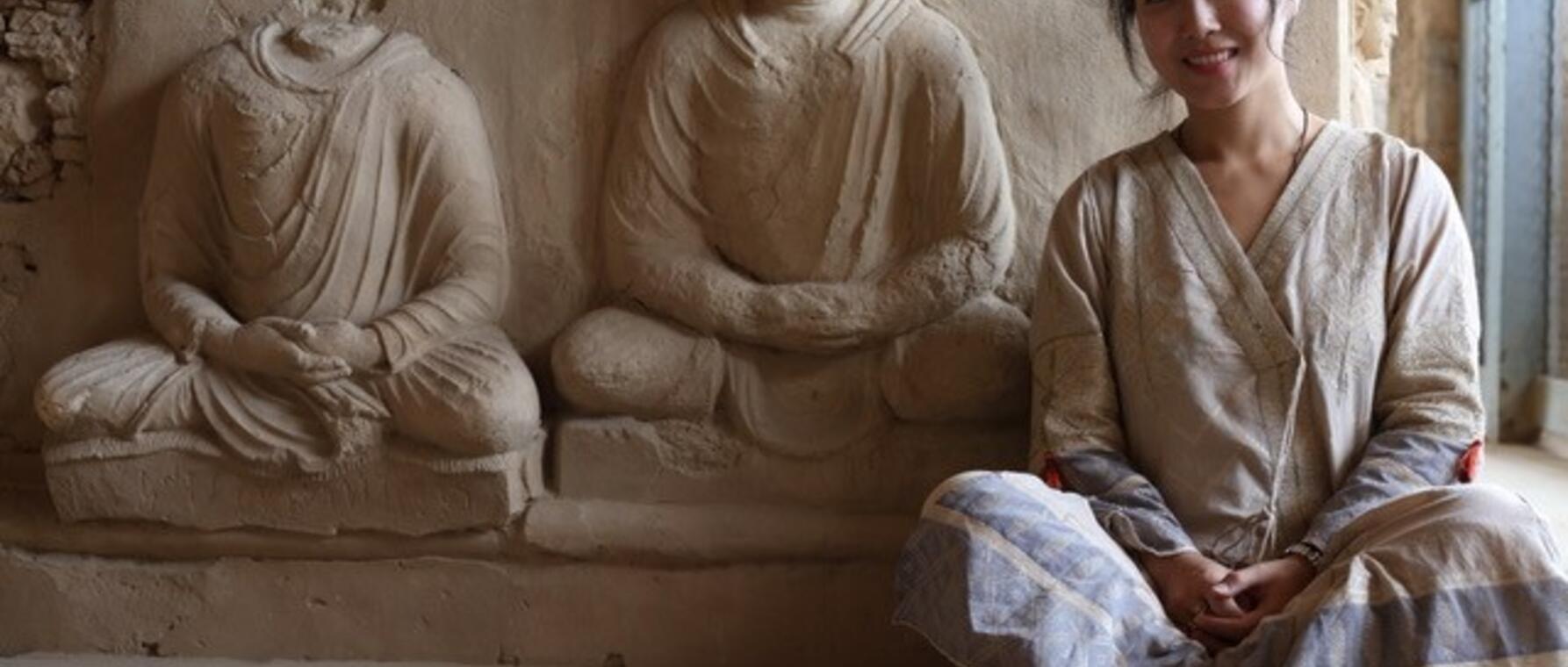

Yunyao Zhai, PhD candidate

Yunyao Zhai is a PhD candidate in the Department of South Asian Studies researching Tibetan Buddhism. She discusses her academic journey from linguistics to religious studies, her work on a powerful Tibetan deity, and her personal connection to Buddhism.

Language Learner, Sanskrit Scholar

I have always had a love of languages. When I was eight years old growing up in Harbin, China, my mom wanted me to learn English. I didn’t want to initially but started loving it after my first lessons and picked it up quite quickly. I knew I wanted to study languages at a higher level and went to university to study modern Greek and French. Once I began, I was drawn to classical Greek, and from there I felt a pull to Greek religion and religious studies. I was interested in the concepts of human destiny and where we go after we die.

Eventually, my academic interests shifted from Greece to Southeast Asia, specifically to Buddhism. Students of the classics are not that much different from scholars of Buddhism, especially when it comes to languages. In fact, a lot of early Buddhism scholars have a background in the classics, and a classically trained scholar like me might find it easier to learn Sanskrit—which, like Greek, is an Indo-Aryan language.

A Wrathful Deity

In 2019, I began my PhD work at Harvard in Tibetan Buddhism. I focus on an esoteric protective deity called Mahākāla widely worshipped in Tibet. Mahākāla is at the center of the Tibetan pantheon but there is little academic scholarship on him. I would like to understand how this deity came to be.

Mahākāla is probably the most popular deity in the Tibetan pantheon where protective deities tend to be very wrathful. That contradicts popular notions of Buddhism. People think about Buddhism or Buddhist deities as calm, cool-headed, and compassionate, but these protective deities are quite scary. You wouldn’t want to encounter one. Mahākāla specifically carries a blood-filled cup made of a skull while walking over corpses.

In Hinduism and Buddhism, there are lots of local deities. Mahākāla started off as one of these. When the Mongol empire was invading Europe and Asia, they used Mahākāla as their war deity, which elevated the deity from a small, regional level to a powerful centralized figure. But why did the Mongols choose Mahākāla out of all the other local deities? My research aims to answer this question.

Scholar-Practitioner

It has been amazing to do this work as a Buddhist myself. A lot of people get their information about Buddhism online (so did I, initially) and it can be very scattered. I want to know where it comes from. Being a scholar-practitioner is a unique experience, because you question a lot of assumptions and beliefs that practitioners take for granted. As a practitioner, the process of scholarship has made my beliefs even more firm. I have tested and doubted them from a scholarly angle, and I still believe.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast