From Russia with Love

How Kenzy Seifert’s experiences in Russia sparked her interest in diplomacy

“These are lucky bus tickets,” McKenzy “Kenzy” Seifert says, flipping over her phone to show me an array of small laminated tickets printed in Cyrillic and lodged under her phone case. “The first three numbers stamped on each ticket add up to the sum of the last three numbers. Traditionally you’re supposed to eat them, but I thought putting them in my phone case would work just as well.”

For Seifert, a master’s student in Regional Studies–Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia (REECA), the Russian bus tickets are more than a quirky souvenir: They are a reminder of the values that prompted her to study international relations.

The Kindness of Strangers

Seifert collected the tickets during a year abroad in St. Petersburg, where she shuttled between her homestay and the university on a local bus route. With only two semesters of language study under her belt, Seifert was still getting her footing when a bus conductor asked for her ticket and began to speak rapidly in Russian. Flustered by the unexpected questions, Seifert replied in Russian: “I don’t understand Russian.” The conductor asked where she was going and then went to confer with another woman. When she returned, she told Seifert: “Go with her, she’s going to your stop.” By the time they got off the bus, Seifert had collected her thoughts and explained to her new traveling companion that she was an American student studying Russian and could find her way safely home.

“These two strangers wanted to make sure I got home safe—and that goes against everything we see in the media [about Russians],” she says, noting the difference between the people and the politics. “We tend to forget that point in our discourse: There is no one Russian, just like there is no one American.”

This experience and others not only influenced Seifert, but also her friends and family who, impressed by the kindness she was shown by the locals, wanted to know more about Russians and Russian life. Seifert’s reflections on her time in Russia and the impact it had on people she knows have inspired her to join the diplomatic corps after completing her graduate studies, with the goal of encouraging positive interactions in foreign countries and improving local understanding and awareness. “My focus is on the micro level,” she says. “I hope to become a public diplomacy officer—the face of America abroad.”

On the Midnight Train to (the Republic of) Georgia

In the REECA program, Seifert focuses on Russian politics, culture, and influence in the former Soviet Bloc. It was another experience abroad, though, that determined her thesis direction. In fall 2018, she spent several months living in the Republic of Georgia on an internship with the US Department of State and became interested in the seemingly contradictory role of the Georgian Orthodox Church in Georgian life.

In Tbilisi, she explains, it was “hard not to notice that the Georgian Orthodox Church is everywhere.” It is, in fact, the most trusted institution in Georgia, with an approval rating of 84 percent. Yet while the church pushes a socially conservative agenda, aligned with that of the Russian Orthodox Church, more liberal Western institutions such as the EU and NATO are also popular. EU flags, for example, are prominently displayed, reflecting public desire that Georgia enter the union. Meanwhile, the Georgian Orthodox Church delicately avoids stepping on the toes of its “sibling church,” that of Russian Orthodoxy. “My focus had previously been US-Russian relations,” Seifert remarks, yet the complex status of the Georgian Orthodox Church—caught between the EU to the West and Russia to the East—is a reminder that “Russia has not only bilateral impacts, but also multilateral impact.”

Endlessly Optimistic

Seifert’s graduate studies and diplomatic ambitions dovetail in many respects. Yet, as a foreign service officer, she would not necessarily continue to work in the Russian sphere of influence and is open to working outside her regional specialization. “I’ve always believed that it’s important to take advantage of timely opportunities,” she says, smiling thoughtfully. “The underlying connections exist, you just have to bring them to the surface.”

In this spirit, she emphasizes that her regional knowledge offers an invaluable foundation in case studies and has taught her how institutions work at a local level. “Being grounded in regional studies will function as a constant reminder that expertise is important, and that if I don’t have it, I should listen to the people who do,” she says.

Such a collaborative spirit underlies her own personal philosophy as well. When asked what advice she would offer fellow graduate students, Seifert gives one of her bright, infectious smiles. “Take people up on their offers to help, to meet with you, to help you find opportunities for the summer, to talk about your goals, to extend friendship,” she urges. “These interactions are important and make the work we do fulfilling.”

Indeed, cooperation is the cornerstone of the work Seifert loves. “We talk about teamwork in education, in business, in an American setting, and then we forget that it is necessary on an international level as well,” she remarks. Reflecting on the reasons why the United Nations and NATO were formed, she worries that the further the world moves away from the strife and trauma that drove those initiatives, the harder it can be to remember why they were established. “We don’t have as much of a social memory now,” she says. “We need to devote attention to the fact that it has been 70 years since the last world war and ask why that is. Something has been working.”

Is that balance now under threat? If it is, Seifert hopes her work might strengthen it. “I believe in American institutions. They can’t function without accountability.” Laughing, she confesses, “It’s an extremely American trait that I’m endlessly optimistic.”

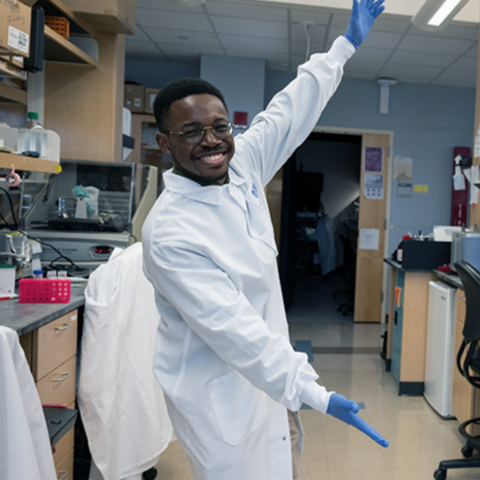

Photo by Molly Akin

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast