Recovering from Coal’s Collapse

Job loss and selective migration in the American heartland

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

As a young woman growing up in southern Indiana, Eleanor Krause traveled each weekend to the Red River Gorge in eastern Kentucky, a haven for rock climbers like her. She grew to love the natural beauty of the site, nestled on the outer reaches of Appalachia—coal-mining country. She loved the people there too.

When Krause went to college at the University of Vermont to study environmental policy, however, she found many who didn’t share her affection. She was startled by the disregard that her classmates and friends had for eastern Kentucky, viewing it merely as a casualty of the coal industry’s environmental impacts.

“Their perspective was, ‘Oh, those coal miners are the ones causing climate change. We need to just ban coal mining,’” she recalls. “And I had this sort of revelation. I realized that I wanted to think about the way that energy and environmental policy impacted the people of Appalachia.”

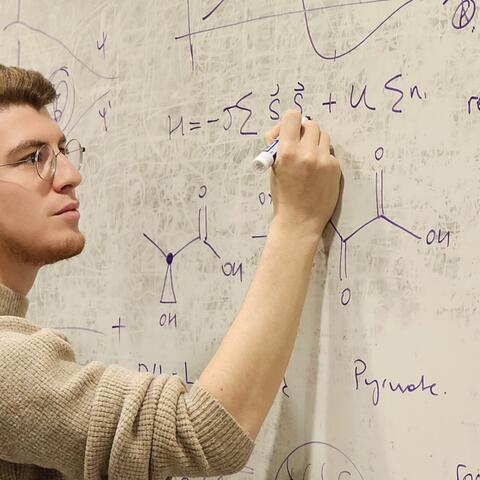

Returning to the Red River Gorge after college, Krause immersed herself in the local community, working with climbing and conservation organizations. She got her master’s degree in public administration with a focus on environmental and economic policy but wanted to make a greater contribution to research in the field. Today, as a PhD student at the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (Harvard Griffin GSAS), her work both lays bare the impact that the decline of the coal industry has had on Appalachian communities and points to ways that policymakers can better mitigate the impact on the people who live there.

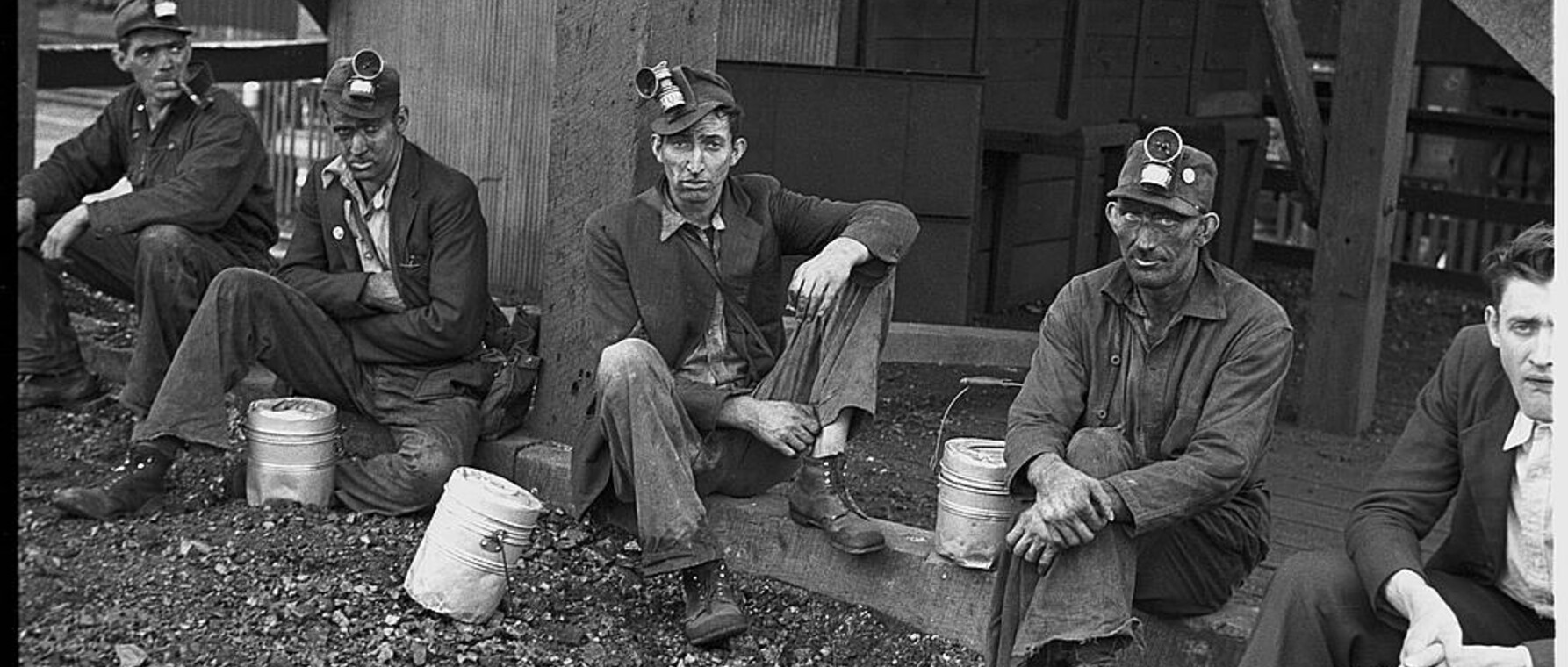

Losing the War

The trajectory of coal mining over the past 60 years is interwoven with the story of poverty and struggle in America’s heartland. In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson stood on the steps of a cabin in Inez, Kentucky, and declared “unconditional war on poverty.” At the time, over 60 percent of Martin County, where Inez is located, lived in poverty and more than half of county earnings came from the coal industry.

Fast-forward to the present: Mining jobs in Martin County have dwindled to only 5 percent of total employment, and the poverty rate has swollen to double the national average.

The lack of human capital, entrepreneurs, and institutional capacity, compounded by historical shocks, seems to create an impasse [for Appalachian communities in transitioning away from fossil fuel industries].

—Eleanor Krause

Krause’s dissertation, titled “Job Loss, Selective Migration, and the Accumulation of Disadvantage: Evidence from Appalachia’s Coal Country,” spotlights the economic and social fallout of this decline. She looks back to the early 1980s when macroeconomic factors—particularly the decline in oil prices—led to a 70 percent reduction in coal employment over a decade. The primary focus of her research, though, is the years between 2007 and 2017, a time marked by a rapid reduction in the demand for coal. In Appalachia, employment plummeted by 50 percent between 2011 and 2016 alone, a seismic shock that caught many off guard.

Contrary to some prevailing narratives, Krause’s research underscores that coal’s decline wasn’t primarily triggered by the shift to cleaner energy sources. She says the causes had more to do with economic forces like the advent of cheap natural gas from hydraulic fracturing. Looking to the future, however, she acknowledges that “increased environmental regulations and policies necessary to fight climate change could continue to drive down demand for coal, increasing the challenges faced by these communities—as well as others built on fossil fuels and energy-intensive industries.”

Krause identifies a distressing pattern. Communities that have experienced significant selective migration or “brain drain,” where college-educated adults leave due to economic circumstances, are disproportionately burdened by contemporary coal shocks. Her research indicates that the effect of the 2007–2017 coal shock on population, employment, and earnings declines is between two and five times as large in places with a greater history of selective migration, and the increase in government transfers per capita is about five times as large.

Krause admits that the implications of her research are sobering. There are few examples of communities “successfully” transitioning away from coal-centered economies. “The lack of human capital, entrepreneurs, and institutional capacity, compounded by historical shocks, seems to create an impasse.”

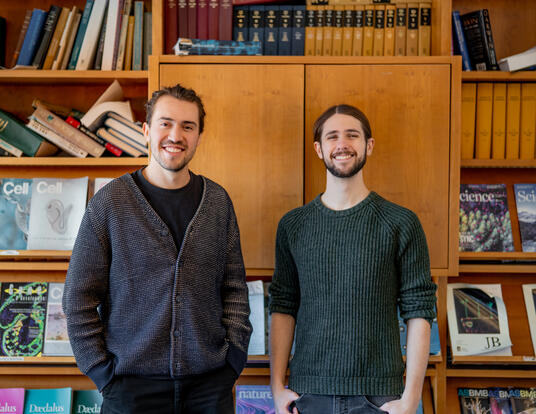

Gordon Hanson, Harvard Kennedy School’s Peter Wertheim Professor in Urban Policy and one of Krause’s faculty advisors, says that her research sounds an important note of caution regarding the transition to a clean energy economy.

“Communities specialized in fossil fuel–related industries are likely to have a very hard time transitioning to a new set of economic activities,” he says. “We need to be thinking hard about how we help these communities make that change, as we strive to forestall a climate disaster for the world as a whole.”

Hope for the Heartland?

In her ongoing research, Krause is analyzing policies like those codified in the federal Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, highlighting the need for a more targeted approach to economic recovery in Appalachia. “While federal assistance provides a lifeline through transfer payments such as unemployment insurance and Medicaid, the emphasis on investing in human capital remains insufficient,” she says. “My policy recommendation would be to focus on that piece of the equation.”

Central to that recommendation is the bolstering of educational opportunities, especially in areas where community colleges are scarce, and broadband internet access, which could offer access both to education and employment opportunities. “Broadband could also encourage a lot of highly skilled individuals to work remotely in a lot of these communities,” Krause suggests.

Eleanor Krause’s research . . . shows us how a shock in one generation can reverberate through the next—an exodus of skilled people now can leave communities short of entrepreneurs and business leaders later.

—Professor Edward Glaeser

Edward Glaeser, the Fred and Eleanor Glimp Professor of Economics and the chair of Harvard’s Department of Economics, calls Krause’s work “important and innovative” and says it sheds light on the economy of one of America’s most troubled regions.

“Eleanor Krause’s research helps us to understand why America’s eastern heartland has suffered for so long,” he says. “It shows us how a shock in one generation can reverberate through the next—an exodus of skilled people now can leave communities short of entrepreneurs and business leaders later.”

By encouraging policymakers to reevaluate their strategies for aiding communities hit hardest by the coal industry’s decline, Krause’s research serves as a call to action. The throughline of her story—from the hills of eastern Kentucky to the campus of Harvard Griffin GSAS—is a commitment to those often overlooked by broader narratives. Through personal connection and academic rigor, Krause hopes not only to unearth the untold story of Appalachia’s decline but also to help inspire a new, more hopeful chapter.

“I hope that my work serves to catalyze a broader research agenda around the unique challenges faced by communities often overlooked by economists and policymakers,” she says. “Anticipated shifts in our economic and energy landscape ahead threaten to disrupt the livelihoods of individuals and communities well beyond Appalachia’s coal country. We will need to do a lot more work to ensure that these shifts do not push already disadvantaged regions into deeper distress.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast