A Passion for Proteins

GSAS Voices: Cyril Kay, PhD ‘56

Throughout its 150th anniversary year, GSAS is foregrounding the voices of some of its most remarkable alumni and students as they speak about their work, its impact, and their experiences at the School.

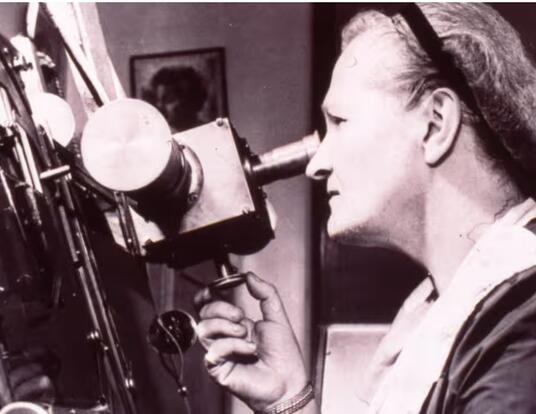

Cyril Kay is a protein biochemist at the University of Alberta who has spent decades studying proteins, the building blocks of the human body. He discusses how he decided to study muscle and other protein systems, his effort to establish multidisciplinary research teams throughout Canada, and what he learned about ethics and integrity from his mentor, Professor of Biological Chemistry John Edsall.

Major Contributions

Much of my research career has been spent studying the structure and function of various protein systems. After receipt of my degree from GSAS in 1956, I went to Cambridge University to do postdoctoral studies with Kenneth Bailey, an outstanding muscle protein biochemist. He had just isolated and crystallized a muscle thin filament protein, tropomyosin. He interested me in carrying out biophysical studies on it. This experience turned out to be a major influence on my life’s work as I decided to concentrate on muscle proteins as one of my major research subject areas when I joined the biochemistry department at the University of Alberta in 1958.

Understanding the biological function of proteins is greatly facilitated by the determination of their structures, and their interaction with other proteins, co-factors, ions, etc. One of the major systems I have focused on is the function of the proteins that make up the thin filament of skeletal and cardiac muscle and regulate contraction, focusing on the calcium-sensitive interactions among the proteins actin, tropomyosin, and troponin. My lab made major contributions to our understanding of the chemistry and structure of both muscle and non-muscle systems and the molecular mechanism by which calcium triggers muscle contraction in both normal and diseased states.

A Group Effort

In 1974, the Canadian government began funding multi-disciplinary research teams called Medical Research Council (MRC) Groups. They asked me and a colleague, Larry Smillie, to co-lead the MRC Group in Protein Structure and Function. In this capacity, we played a major role in the recruitment of group members representing expertise in all the paradigms of protein chemistry, all of whom subsequently became stalwarts in the local, national, and international biochemical communities.

From the outset, the group worked most effectively together, discussing common problems, providing protein preparations to each other, and collaborating in both a formal and informal sense. From 1974 to 1995, group members published over 1,600 articles in the most prestigious biochemical journals and delivered scientific presentations in international forums. We also trained some 250 graduate students and postdoctoral fellows.

Our research was diverse with basic discoveries and unique contributions to science. In addition to our muscle work and its implications for cardiovascular conditions, some other practical applications were in the infectious disease area. These included the design of anti-microbial peptides to target gram-negative bacteria such as pseudomonas, as well as gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus to resolve the growing problem of increased resistance to traditional antibiotics.

Rejecting McCarthyism

At GSAS, I was most fortunate to select John Edsall as my PhD advisor. He was an incredible teacher: friendly, inspiring, patient, thorough, and always stimulating. Among my strongest recollections of that period with John was his astounding memory and his love of fundamental science. He was always accessible—no question was too trivial—and whenever I had a problem, he would stride to the blackboard where he derived and graphed the equations for me in detail.

I also recall that this was a time when John was willing to speak out on issues in which science intersects with other parts of society. For example, during the McCarthy era of the 1950s, the US Public Health Service was revoking the research grants of investigators because of unevaluated adverse information in their security files. The investigators were not told what was going on or allowed to answer the alleged charges which were, in any case, irrelevant to the criteria for awarding grants for unclassified research.

John Edsall took the courageous and leadership stance of writing an article in Science, in which he resolved neither to ask for nor accept funds from any government agency that denied support to others for unclassified research for reasons unconnected with scientific competence or personal integrity. Subsequently, and certainly, in part because of John’s leadership, the Eisenhower administration called on all government agencies to stop the abuses and to follow accepted procedures.

After leaving Harvard in 1956, I kept in touch with John until his passing in 2002. I consider myself most fortunate to have had a long-lasting friendship with such a great human being in whom science, humanism, and society were always inseparable.

Photos Courtesy of Cyril Kay

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast