Music as Theater

How avant-garde performance redefines music’s possibilities

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

Imagine settling into your seat at Symphony Hall to face a stage filled not with an orchestra but with an overwhelming assortment of equipment: old radios and television sets, speakers of various shapes and sizes, electrical wires and cables, an old Victrola phonograph, and a cassette player or two. As the lights go down, the speakers begin to play scattered sounds of footsteps, clinking wine glasses, indistinct background chatter, and faraway laughter. Soon, thereafter, a single performer emerges on the stage and interacts with the electronic devices, disconnecting and reconnecting wires with exaggerated flourishes, carefully brushing dust from a TV screen, and then forcefully throwing a radio onto the floor, adding a dull crash to the array of sounds gradually filling the room.

While this peculiar spectacle might sound unusual for a concert hall, it would be perfectly typical as a rendition of the late Argentine-German composer Mauricio Kagel’s (1931-2008) piece Antithese (or Antithesis), an experimental music theater work composed between 1962 and 1963 that calls for “an actor with electronic and public sounds.”

Kagel’s Antithese is intended to surprise audiences by playing with expectations. “Oftentimes, it takes place in a traditional performance space like a concert hall,” explains musicologist Elaine Fitz Gibbon. “So, the piece uses the trappings of traditional canonical music performance to ask you to rethink all of your expectations about hearing and viewing a concert: what to look at, who is the musician, what is the instrument, is this music? Is it theater? How should I react?”

As a PhD candidate in the Harvard Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS), Fitz Gibbon focuses on experimental music theater composition and performance, tracing the history of this genre from its beginnings in the late 1950s as a product of migration and cultural exchange between Argentina, West Germany, and the United States. By studying composers in this avant-garde genre, best known by its German name, Musiktheater (or “music theater”), she hopes to help audiences rethink what the possibilities of music can be—and who belongs on stage.

Extreme Theatricality and Sonic Strangeness

Fitz Gibbon argues that avant-garde Musiktheater has political significance, as many of its more prolific practitioners have belonged to marginalized groups in their societies, including immigrants, Jewish composers who fled the Nazi regime, and women composers working in a male-dominated avant-garde scene. “My work in exploring this genre, which is not particularly well known and generally has been neglected in the histories of this era, is to say that Musiktheater is a space for composers who were othered, who didn’t necessarily belong, to think about the political consequences of their art, and to imagine a kind of music-making, listening, and hearing that encompasses all varieties of identities,” she explains.

Take Kagel’s Antithese as an example. According to Fitz Gibbon, Antithese is important not only as a work of extraordinary theatricality and sonic experimentation but also as a statement about the implicit biases baked into concert performance procedures. When we think of a typical classical music concert, she explains, there are “things that we take for granted, like that the performers are going to come out probably wearing black and white suits, tuxedoes, or evening attire . . . They're going to use their bodies in a certain way. They're not going to flail their arms––unless, maybe, they’re conductors––and they're going to walk straight, maybe a little stiffly. They're not necessarily going to speak with the audience.”

What the practitioners of [Musiktheater] began to argue is that the rituals of concert music are socially constructed. They . . . allow for certain people on the stage, and not for other kinds of people, based on categories of race, gender, country of origin, and accented speech, for instance.

—Elaine Fitz Gibbon

Kagel’s Antithese dramatically breaks from these expectations. His goal in doing so, Fitz Gibbon says, was to encourage critical thinking about how, even in more typical concert performances, all of the actions taking place are theatrical in some way. Every participant in a musical event––even the listener––plays a role, since social and cultural norms teach and enforce certain ways to behave.

A performance of Antithese makes this point by subverting those norms. Kagel’s piece repurposes the traditional concert hall by making it a backdrop for unexpected and exaggerated movements by the performer, dramatic and unusual interactions with music-related electronic equipment, and a musical sound-world based on the ambient noises of crowds of people—sounds of a booing audience, of a soccer match, and of a cocktail reception—that Kagel recorded and mixed with electronically generated music at the Siemens Electronic Music Studio in Munich.

“What the practitioners of the genre began to argue,” she explains, “is that the rituals of concert music are socially constructed. They have a long history and legacy that are very complex, that allow for certain people on the stage, and not for other kinds of people, based on categories of race, gender, country of origin, and accented speech, for instance. Ultimately, Musiktheater in the hands of composers like Kagel and others, including Sylvano Bussotti or Cathy Berberian, proved that all music, whether it claims to be theatrical or not, is always theater.” By playfully challenging norms for performance, Fitz Gibbon argues that composers of Musiktheater also challenged prejudices and patterns of exclusion that they saw in the art world.

As an Argentine composer who moved to Germany in his mid-twenties, Kagel had personal experience of being treated like an outsider. Accordingly, undermining norms for performance was a powerful way for him to aesthetically respond to a challenging lived experience––and to produce work that was artistically inventive in itself. As Harvard’s James Edward Ditson Professor of Music Anne Shreffler, one of Fitz Gibbon’s advisors, explains, “Kagel settled in Germany and then proceeded to overturn practically every assumption that ruled European post-war composition.”

Despite the importance of Kagel’s innovations, it is often difficult to access information about the composer and his works in the present day. It’s very rare now for Kagel’s works to be performed live, which requires Fitz Gibbon to use a wide variety of methodologies to piece together a vision of what these pieces would have been like to perform and experience.

“I look at published musical scores,” she says, “but I also have traveled to look at evidence from a lot of different archives, both in the United States and throughout Germany and Switzerland.” Other crucial sources of information have been interviews with festival directors (whose events included Kagel’s works); Kagel’s biographer, Werner Klüppelholz; Kagel’s composition students; performers of Kagel’s works from the US, Germany, and Argentina; and his friends.

In addition to this fact-finding work, Fitz Gibbon takes a novel analytical approach to the history of Musiktheater, allowing her to tell stories that are often overlooked. As Professor Shreffler explains, “Elaine's dissertation builds on the idea of an avant-garde diaspora to provide a new view of the stunning variety of experimental music theater that flourished in Germany and the US since [the 1960s], emphasizing the significance of transatlantic exchange and migration.”

Harvard’s William Powell Mason Professor of Music Carol Oja, also one of Fitz Gibbon’s advisors, says that by thinking about Musiktheater in terms of its networks of circulation, Fitz Gibbon “pushes past nationally defined studies of twentieth-century conceptual art and music theater, and she reinstates a core group of women to this historiography.” For example, one key figure in Fitz Gibbon’s research is the visual artist Ursula Burghardt (1928-2008), who was also Mauricio Kagel’s wife. Though she is not usually cited as a part of experimental music history, Burghardt’s collaborations with Kagel and with other avant-garde artists and composers were essential to the success of their now better-known work. Fitz Gibbon also says Burghardt’s own artistic work challenges and changes how we might define a composer, a musical instrument, or even music itself.

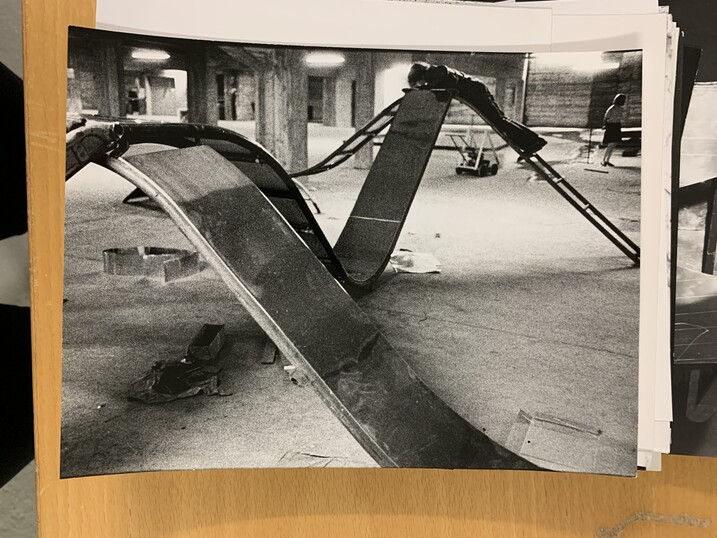

“Burghardt’s sculptural environment Krumme Ebene (or Crooked Plane) (1968), for example, was a series of overlapping slides, made of iron and covered in aluminum, and with different drop levels, so some are higher off the ground than others,” Fitz Gibbon explains. “Then she set up speakers and contact microphones on the slides themselves and on pillows that you would drop onto after you slide off the slide. It all took place in this underground garage, so you can imagine it's an extremely acoustically live space. It’s like a carnival atmosphere, with shouting children, and adults having fun, laughing.”

A Human Story

Individual origin stories are also personally important for Fitz Gibbon. Hers begins with her mother. As a ceramic sculptor working in the traditionally male-dominated fields of fine art, Fitz Gibbon’s mother inspired her to think critically about how structures of marginalization impact the experiences of artists, as well as the stories we tell about music and art history. Fitz Gibbon likewise credits her mother for encouraging and supporting her studies of the cello starting at the age of five—even accompanying her on the piano—and her father for sharing his love of opera and taking her and her sister, soprano Lucy Fitz Gibbon, on frequent trips to the nearby San Francisco Opera. Following her early childhood experiences with the cello in California, Fitz Gibbon continued to study music quite seriously. She had plans to be a professional cellist and studied at the New England Conservatory (NEC) until an injury forced her to leave the program. While at NEC, however, Fitz Gibbon for the first time took some classes in musicology. She was hooked.

“I'd never really thought that much before about how complex and just how nuanced and intertwined the history of music can be with the lived experiences of people, with literature, and with other arts,” she says. “So, after I left NEC, I double-majored in music and German at the University of Pennsylvania. And that's when I really became more interested in musicology. I found it just endlessly fascinating.”

Kagel settled in Germany and then proceeded to overturn practically every assumption that ruled European post-war composition.

—Professor Anne Shreffler

Fitz Gibbon’s PhD research at Harvard has allowed her to pursue work that draws on the range of skills and knowledge she has developed in the disciplines of music, German studies, and Latin American Jewish studies. She’s even found some time to play the cello again, both in the orchestra of the Student Center at Harvard Griffin GSAS and in the Harvard Baroque Orchestra based in Harvard’s Memorial Church. “That community is something I really appreciate about Harvard,” she says.

Indeed, community has been a crucial theme in Fitz Gibbon’s research. The music theatrical works she studies, she explains, require a variety of collaborators that make them possible: composers, actors, performers, visual artists, set designers and builders, festival and concert organizers, and more. “Also, in my own work,” she reflects, “I couldn’t have done any of this without the help of so many people—of friends, of archivists and librarians, of really kind interview subjects who generously put me in touch with others, with their friends, and colleagues. I am indebted to these many people and communities; they came together across languages, time zones—even pandemic Zoom-fatigue—and continents.”

Fitz Gibbon says the experience of researching Musiktheater has made her appreciate the ways in which the genre’s history is fundamentally a human story. “Thinking about art and music and their roles in society—it is a history of collaboration,” she says. “I hope my work opens people’s thinking about that collaboration as something that is always there in music. But I also hope that my research shows the ways that music is so deeply engaged with private, personal histories and interests in addition to the more public, large-scale, grander histories and political issues.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast