Minding the Gap

Exploring the impact of inequities on the health of transgender and gender-diverse people

In 2021, over 100 bills were introduced in 33 US state legislatures to restrict the rights of transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) individuals. The wave of legislation has continued in 2022, with measures that restrict medical care for transgender youth, exclude them from athletics, and curb access to accurate identification for transgender adults. Of an Arkansas law passed in 2021, prohibiting physicians from providing gender-affirming treatment for trans people under age 18, the American Civil Liberties Union said the measure would "drive families, doctors, and businesses out of the state and send a terrible and heartbreaking message to the transgender young people who are watching in fear.”

Health policy scholar Alex McDowell says that such legislation has a devastating impact on the health of TGD people.

“Policies that prevent clinicians from providing gender-affirming care to young people are incredibly harmful,” McDowell says. “We know that 40 percent of transgender and gender diverse people report a suicide attempt in their lifetime. That’s compared to less than 5 percent of the general population. I hope that I'm wrong, but I worry that lives will be lost because of these laws.”

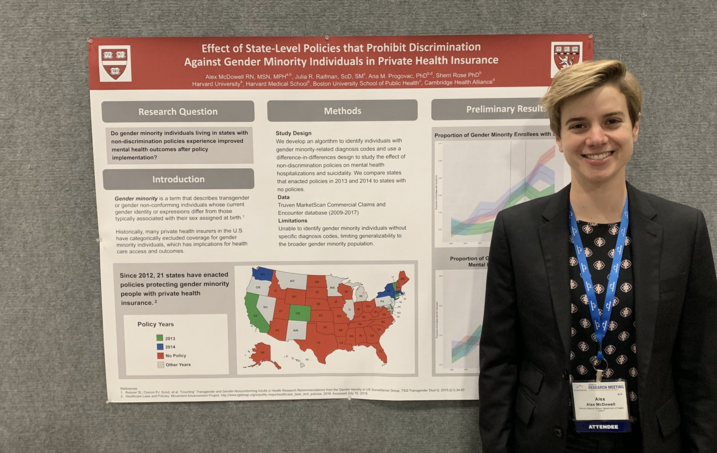

As a postdoctoral researcher at the Mongan Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, McDowell, PhD ’20, works to uncover the inequities that affect the health of those in the LGBTQ community—especially those who identify as TGD. A former psychiatric nurse, McDowell hopes their research will advance understanding of the impact of discrimination against gender-diverse individuals and increase access to lifesaving care.

Research shows that access to gender-affirming care improves mental health.

—Alex McDowell, PhD ’20

A Troubling Story

Most probability samples in the United States—including the US Census—don’t collect data on sexual orientation or gender identity, making it difficult for researchers to identify health trends in the LGBTQ population and to identify inequities. McDowell says the data that do exist tell a troubling story.

“We know from available evidence that LGBTQ populations experience inequities, both in terms of physical and mental health,” they say. “In order to develop interventions to address these inequities, we need to have data on sexual orientation and gender identity. These data create a research infrastructure.”

As that infrastructure develops, it highlights variation in mental health throughout the LGBTQ community according to gender identity, race, ethnicity, and even geography. For example, McDowell points to a recent article by Dr. Elle Lett, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, that identifies ethnoracial inequities in mental health and access to gender-affirming care within TGD communities. McDowell’s work focuses on the TGD population where they aim to understand how to mitigate inequities in mental health.

“We find increased prevalence of a number of conditions among gender diverse individuals, including depression, anxiety, and suicidality,” they say. “But perhaps most importantly, research shows that access to gender-affirming care improves mental health.”

McDowell’s findings are reflected in the data presented by Harvard’s Task Force on Managing Student Mental Health in its July 2020 report. “Those identifying as ‘Other gender’ (transgender, non-binary, genderqueer) report much higher rates of diagnosed mental disorders (48%) than those who identify as cisgender female (21%) or cisgender male (9%),” the Task Force wrote. “Those identifying as BGLTQ report higher rates of diagnosed mental disorders (30%) than non-BGLTQ (12%).” McDowell says that while the types of mental health conditions experienced by members of the LGBTQ community vary, they have a common thread: minority stress. For TGD individuals, minority stress, including gender identity non-affirmation, gender-related discrimination, and gender-related violence, is also linked to worse mental health.

“It's this idea that trans people experience frequent and persistent stressors related to their identity or society’s rejection of and violence toward their identity, that results in increased incidence of depression, anxiety, suicidality, or substance use disorders,” McDowell says. “And for individuals with intersecting identities that have been historically marginalized, for example, trans women of color, these stressors are compounded.”

McDowell’s research uses large nationally representative datasets—including claims data from Medicare and private payers—to better quantify the inequities faced by gender-diverse patients in the healthcare system. Benjamin Cook, one of McDowell’s doctoral advisors and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School, says that their experience as a nurse and a scholar enable them (McDowell) to approach health policy research from a unique vantage point.

“Alex’s questions are grounded in their combination of rigorous methodological and clinical training,” he says. “And Alex has a foundational desire to gather, and learn from, gender diverse patients and community members to study clinical and policy questions that are of real relevance to the TGD community, and to interpret findings in an inclusive and thoughtful manner.”

A Huge Baseline Inequity

The goal of McDowell’s research is to gauge the impact of health care policies on TGD health and access to gender-affirming care—including hormone therapy, surgery, and mental health care. Access to much of this type of treatment is restricted in the United States. Even where it is not, there is a shortage of medical professionals trained to provide gender-affirming treatments. And then there’s the problem of health insurance. “Even though the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Psychological Association (APA), and numerous medical professional organizations say that gender-affirming hormones and surgery are medically necessary and effective interventions, many insurers refuse to cover these services,” McDowell says.

[This] was really the first [study] to examine the impact of nondiscrimination policies on the health of TGD individuals.

—Sherri Rose

In a study published in JAMA Psychiatry and co-authored by Dr. Julia Raifman, Dr. Ana Progovac, and Dr. Sherri Rose, McDowell detailed the impact of health insurance nondiscrimination policies on gender diverse individuals. McDowell cites data from a 2015 survey that shows that, among those with private insurance who tried to access gender-affirming surgery, over half were denied coverage, as were around a quarter of those who tried to access gender-affirming hormones. They and their colleagues sought to evaluate the effect of these policies on suicidality among gender-diverse individuals.

“We looked at the period from 2009 through 2017 and found a notable impact on trans and gender diverse folks who lived in the 20 or so states that prohibited insurance companies from discriminating based on gender identity,” they say. “These laws didn’t necessarily require insurers to cover gender-affirming care, but they did force insurers to remove exclusions of coverage for this care. Even so, these state-level policies were associated with decreases in suicidality among transgender and gender-diverse individuals. For TGD individuals living in states that implemented these policies in 2014, for instance, suicidality dropped by 52 percent.”

In the same study, McDowell and their colleagues compared suicidality among people who were identified as transgender and those who were not. The rate for the non-transgender sample hovered around half a percent throughout the eight-year study period. The rate for the transgender sample grew from two or three percent to over six percent. “There's just a huge baseline inequity in suicidality and what we find is that these non-discrimination policies may begin to address that,” McDowell says.

Dr. Sherri Rose, McDowell’s dissertation chair and an associate professor of health policy at Stanford University, says that the JAMA Psychiatry study was developed during McDowell’s PhD work at GSAS. “It was really the first to examine the impact of nondiscrimination policies on the health of TGD individuals,” she says. “We built on Alex’s prior work, which developed a new diagnosis-based algorithm for identifying gender minority individuals in commercial claims data, in order to study the impact of these nondiscrimination policies. Alex was a leader in all aspects of this research.”

It is precisely because of the results of their research on TGD populations that McDowell is so concerned about the anti-transgender legislation making its way through dozens of states. They say these new laws stand in opposition to the evidence on gender-affirming care.

“Because of transphobia, fear and uncertainty are attached to healthcare that has been demonstrated over and over again to be medically necessary and effective,” they say.

Rose says that McDowell’s research can serve, in part, as an antidote to anti-transgender legislation. “The policy implications of Alex’s work are substantial as we see harmful new policies proposed in states that would ban gender-affirming care,” she says. “The importance of the results and the rigor of the research led to Alex’s work being cited in publications such as Scientific American and The Hill.”

For TGD individuals living in states that implemented these [nondiscrimination] policies in 2014, for instance, suicidality dropped by 52 percent.

—Alex McDowell, PhD ’20

Although McDowell is concerned about the impact that the recent wave of legislation will have on transgender populations, they speak with enthusiasm about the growing number of students and scholars interested in LGBTQ health policy—and the opportunity to train them. McDowell is in the process of submitting proposals for grant funding that would allow them to study which state-level policies are most effective in improving LGBTQ health. And they are hopeful that the states now passing anti-TGD laws reverse course and join others in opening access to healthcare and supportive services for communities.

“My hope is to generate evidence on how effective gender-affirming policies are designed and implemented,” McDowell says. “I want to study which parts of them are more effective and which are less. Most of all, I want my research to inform the design of future policies so that when the rest of the states decide to implement these laws, which they will at some point, we will have evidence on the most effective ways to improve LGBTQ health through policy.”

Photos courtesy of Alex McDowell; Banner by Shutterstock

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast