Medieval Google

Ryan Low, PhD Student

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

Ryan Low is a PhD student in the Department of History where he studies high medieval Europe. Low discusses his research on notarial contracts, how these documents provide a window into the minds of people in the Middle Ages, and how teaching at Harvard has inspired his work.

The Computers of the Middle Ages

I study the history of technology. I see notaries—publicly licensed scribes who wrote contracts—as the computers of the Middle Ages.

Historians have studied notarial contracts, public documents that could pertain to any sort of transaction from small-scale subsistence loans to testaments or dowries or property transfers, primarily as a legal technology that works the same way and is used the same way everywhere, but that’s only partially true. I explore how changes in how contracts worked and were used transformed how people communicated. The impact was analogous to how computers completely rewrote how people communicate today.

One of the biggest changes is the invention of paper in Europe. Before the arrival of paper, contracts were written on parchment, which is animal skin. You had to kill an animal to write. Making paper is a much less intensive—and expensive—process than making parchment, so writing became much more accessible.

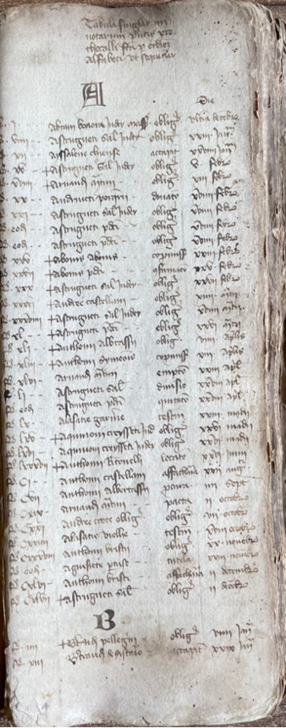

Paper made writing contracts a lot easier. As a result, the number of documents written by notaries exploded around the 14th century, going from thousands to tens of thousands to millions. With paper, you could produce tens of millions of contracts. You could make copies of things you would not have made copies of before. You could write things down that were of short-term importance. You could leave blank space on pages so you could write in the margins and format the pages in a more legible way.

Paper revolutionized notarial contracts. Before, notaries would write contracts on whatever they could find, but with paper, they started devising their own practices of recordkeeping, formatting, and design. Some notaries wrote all their contracts in a big block of text, others were very divided and neat. Some gave titles and page numbers, others didn’t. I want to understand why these differences occurred.

Beyond Keywords

One of the aspects of notarial contracts that I’m very interested in is how notaries retrieved information. When you type a keyword into Google, one of the ways the search engine retrieves information is by showing you everything that matches the term exactly. It can also search for information by matching words that are similar to the search term.

In real life, we retrieve information very differently. If someone in the Middle Ages was looking for a marriage contract, they might say, “It happened a few years ago. It involved my brother. There was some land transferred in the marriage.” There are no keywords in real-life queries, so the notaries couldn’t be straightforward in their recordkeeping. Some notaries ended up having really elaborate indexes that were organized alphabetically, by date, by name, and by type of contract. If you tried putting these indexes into Excel it would be a disaster!

To understand the logic behind the indexing of the notaries, you have to study how debt worked, and how marriage worked. It’s a difficult process because the notaries were not thinking about how to make their records easy for the general public to access. We have to reverse engineer their process and decipher how it worked.

Inspired by Students

My most cherished memories at Harvard are of teaching. I led my first section during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was not the best moment to learn how to teach. But my students were great, and we had a lot of fun.

When we got back to in-person coursework, I was a teaching fellow for Deep History, an interdisciplinary general education course taught by professors Matthew Liebman and Daniel Smail. We met inside the Peabody Museum and worked with a lot of material objects. The projects my students came up with and the questions they asked have inspired my own research. They are the reason I enjoyed writing my dissertation, "Notarial Information and the Production of Knowledge in Rural Society," as much as I did. I probably learned more from them than they did from me.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast