Maternal Mental Health Matters

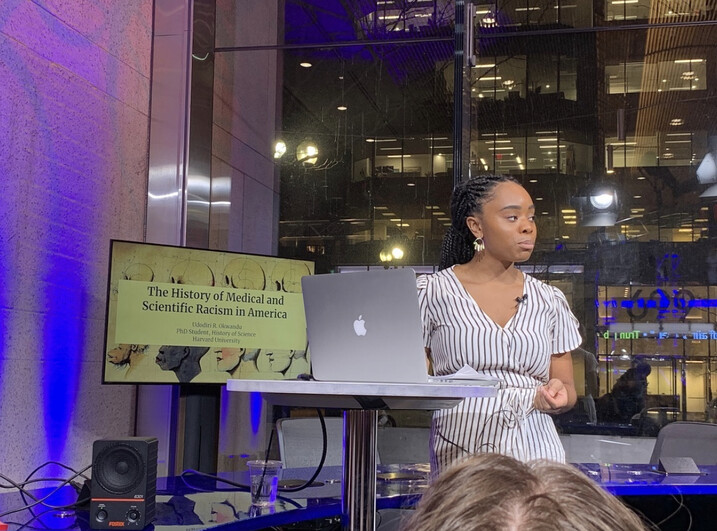

Harvard Griffin GSAS Voices: Udodiri Rosemary Okwandu, PhD Student

A student in the Department of the History of Science, Udodiri Rosemary Okwandu researches how scientific and medical understandings of maternal mental illnesses—such as postpartum depression and psychosis—have been used to rationalize the “transgressive” behavior of childbearing women from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century. She talks about how being one of seven daughters of a nurse inspired her interest in maternal health, the way that race has shaped perceptions of motherhood, and how diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to mental illness have tended to reinforce the ideal of the white, middle-class, domestic mother.

A Passion for Equity

My passion for understanding inequities in medicine and racial health disparities stems from my personal experiences navigating the healthcare system as a Black woman and observing the challenges marginalized communities face within healthcare settings. I have also been interested in issues related to pregnancy, motherhood, and family because I come from a massive family. I am one of seven daughters, so I constantly find myself drawn to the ideas of family and mothering—and the way those ideas were shaped by race. People would say things to me like, “Oh, you can’t possibly have the same parents. All your siblings can’t possibly have the same parents, right?” It’s like, why would you say that? What assumptions are you making about the structure and nature of Black families? The comments bothered me.

I think I was also inspired by talking to my mother about her experiences as an immigrant to the US and what it was like to raise a family here. She shared her traumatic birth experience with me. After a challenging delivery that would ultimately land me in the neonatal intensive care unit for several days, the doctors accused my mother of being on drugs since I was “unusually” fussy and crying too much (which they read as a sign of drug withdrawals). These accusations took place in a Los Angeles hospital, in the nineties, during the peak of the crack epidemic.

It’s a painful memory for my family. My mom never used drugs, and she’s a nurse herself. So when they asked her that question—and subsequently tested her for drug abuse—it was not just a terrible accusation; it was deeply unjust.

My sister is an obstetrician-gynecologist, and I have done some work related to that field. But the specifics of my PhD project and the desire to follow it came out of the increased studies around the criminalization of motherhood, especially women suffering from postpartum depression, and the disparities that we’re seeing. I essentially thought, “I want to historicize this. I want to see where this is coming from.” And that’s how I landed at Harvard Griffin GSAS.

Maternal mental health is a major issue today that I think requires more attention, and it only got exacerbated during COVID-19. Rates of postpartum depression and other disorders rapidly increased during the COVID period, and many medical spaces are not equipped to deal with it, whether it’s outdated screening models or just a lack of knowledge or information about how bias shapes these conditions. That’s what has drawn me, and that’s what’s motivating me to continue working on this.

Challenging the Boundaries of Motherhood

My project is called “Transgressive Motherhood: Maternal Mental Illness, Diagnostic Privilege, and Race in American Psychiatry.” I am delving into a period from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, specifically from 1890 to 1970. You see, maternal mental illnesses are essentially mental disorders associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. While today such illnesses are called perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMAD), across the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries they were described using other names, including puerperal insanity, puerperal mania/melancholia, and psychoses of pregnancy.

But what’s fascinating about these disorders is how they have undergone significant shifts in classification over time. That’s why I prefer to call them “maternal mental illnesses,” considering the way they have evolved. As a historian of medicine, I have dedicated my efforts to examining how ideas of race and racial differences have influenced medical practices, from the creation of diagnostic categories to therapeutic approaches and more.

I am essentially exploring how racial science and the racialized perceptions of motherhood have shaped the classification, diagnosis, and treatment of maternal mental illnesses in the United States. You know, these disorders have historically served as both a defense and an explanation for women who challenged the conventional boundaries of ideal motherhood. It could range from emotional or mental instability to neglecting themselves, their children, or their homes, and in extreme cases, even violence or self-harm.

What I find particularly interesting is that these disorders have often been seen as race-neutral by historians, with a focus solely on how they are gender- and sex-based diagnostic categories. However, my research suggests that medical understandings of these disorders have been significantly influenced by an American obsession with prioritizing and protecting white mothers and the ideal of white motherhood. This obsession has served nationalistic interests, but it’s problematic not just for nonwhite sufferers who are disproportionately underdiagnosed or pathologized when diagnosed, but also for white female sufferers whose experiences have been understudied and neglected, often leading to their policing by the medical system.

Raising the Visibility of Maternal Mental Illness

I am essentially investigating how medical constructions of these disorders have been shaped and perpetuated by the American ideal of the white, middle-class, domestic mother, and how diagnostic and therapeutic practices have reinforced these constructs. The illnesses are highly visible but significantly understudied even though roughly 10 percent of mothers suffer from them, a number that may be increasing. However, historically, medical investigations have been scattered across different fields, from psychiatry to obstetrics and gynecology. So I have adopted a case study approach, focusing on key moments in history when maternal mental illness gained visibility.

For instance, I have explored the intersection of law and maternal mental illness, particularly how it became relevant in criminal trials, especially for women charged with homicide or infanticide. This became a crucial turning point for maternal mental illness as before the 1890s, there was little discussion about it. The disorder’s racialization started becoming overt, with associations made between it and white Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic women, as well as civilized women. This is a prime example of how these disorders were explicitly linked to race.

My upcoming research will focus on the intersection of maternal mental illness, poverty, and family planning in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City. I will be examining publications, medical documentation, and New York state policies related to poverty prevention, as well as community organizing documents. I hope to provide some insight into the complex interplay between race, class, and gender in the history of maternal mental illness in the United States.

Banner photo by Tony Rinaldo

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast