Harvard Horizons Podcast: The Secret Words of Mary, Queen of Scots

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

“When all else about an individual dies or is devoured,” writes Harvard PhD student Vanessa Braganza, “ciphered documents [those written in code] can preserve their identity beneath the calcified surface of history.” In this episode of the Harvard Horizons podcast, Braganza explains how the secret letters of Mary, Queen of Scots, written in code, upend our notions of the doomed royal as a woman with no agency, swept under by a powerful leader and the currents of history.

This transcript has been edited for correctness.

Codes are puzzles. A game just like any other game. Well in Renaissance England, the game was on. The 16th and 17th centuries saw a revolution in cryptography unparalleled until the code-breakers of World War II. This was a time when kings and queens had to guard against vultures at their backs, for between themselves and rival claimants for the throne, there lay a precipice over which they could fall all too easily.

The rise of state secrecy created a game of survival that turned on people's ability to conceal sensitive information in secret symbols, a practice known as ciphering.

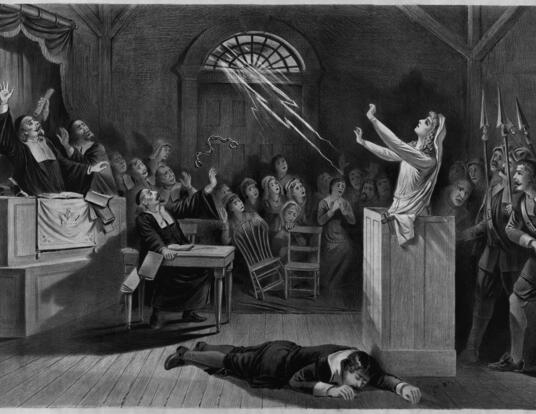

The Renaissance presents us with a paradox. Symbols and ciphers had the power to liberate people's voices by locking them up. There is perhaps no better example than Mary, Queen of Scots. For nearly 500 years, history has regarded Mary, Queen of Scots as a tragic victim of fate. Betrothed at the age of one, her third husband assassinated her second husband before kidnapping and marrying her. Betrayed and imprisoned for 19 years by her cousin and rival Elizabeth I when she fled to her for help. And finally executed in 1587.

But that's not the end of the story. As Mary herself would write, in my end is my beginning. So, let's begin at the end. During her nearly two-decades-long imprisonment, Mary was anything but silent. She filled the world with words, words not only written but painstakingly embroidered. Words that wove her story and tried to change it unsuccessfully.

But these words have gone largely unheard. The reason? They're in cipher. Mary produced this piece of embroidery towards the end of her nearly two decades-long captivity. The central monogram is a cipher that decodes to the names Elizabeth and Mary. The Latin motto around the border, “Arctiora Sunt Virtutis Vincula Quam Sanguinis,” translates to, “The Bonds of Virtue are Tighter Than Those of Blood.”

Elizabeth would actually pretend to be helping Mary even as she imprisoned her, but the trampled Scottish thistle underneath that massive monstrous monogram tells a different story. Mary's story. That even though Elizabeth's thin pretense of being Mary's ally, she was trampling her underfoot. She was betraying a kinship tie.

Mary produced this embroidery towards the end of her imprisonment, but she had, in fact, been dealing in ciphers from the very beginning. During this time, she was also sending enciphered letters left and right to Scotland and France. These ciphers, these letters made use of a simple substitution system that is one symbol for every letter of the alphabet.

Here is one of the earliest, written in the second year of her imprisonment to the Scottish Bishop of Ross written in cipher and also written in Middle French. In it, Mary recounts a kind of mutual interrogation between herself and her jailer, Sir Francis Knollys, in which she plies him for information about the ongoing legal proceedings against her for complicity in her third husband's assassination of her second husband.

"Sir Francis Knollys pretended yesterday that he had learned nothing, yet well I know that if he had something that could benefit me, he would not advertise it. On the contrary, he wishes to 'draw the worms from my nose' to draw my secrets out. And for that, I have answered him as little as possible to keep him in suspense and doubt."

Besides being a colorful source of idioms, this letter reveals Mary to be an astute political chess player, well aware that her very survival depended on her ability to be several steps ahead of her opponent at all times and that this necessary advantage hinged on her ability to conceal and reveal and even solicit sensitive information.

These two examples barely scratch the surface of the unplugged archive of Mary's codes. And Mary's story barely scratches the surface of the dangerous games that people were playing with codes in the Renaissance. At the same time, some cryptographers actually pretended to be sorcerers and concealed their codes and ciphers in fake spells, the better to keep their sensitive expertise under lock and key. This practice of hiding one plain text within another is known as steganography and is still used today.

At the same time, courtiers and writers splashed ciphered and monograms, much like Mary's, across the covers of books and wore them as jewelry.

Ciphers teach us to search for the secret passageways and trap doors of history. And this is what I do for a living as a literary historian, or, as I prefer to think of it, a book detective.

So here is my challenge to you. You were each given your own cipher wheel as you arrived here today. And the coded message on the screen behind me can also be found in your programs. Most people think of history as something that exists within the covers of books or through the glass cases of museums, but what does it say that someone as well-known as Mary Queen of Scots, whom I'd be willing to bet everyone in this room has heard of, has managed to go unheard?

This history invites us to step inside. And so, I invite you to do what I do for a living. Cast yourselves as the detectives, step inside the Renaissance's game of masks and shadows, and let's see if you, too, can crack the code, because Mary's story is not the end. Ciphers teach us that what appears to be the last word on a subject or a person and her voice may well be just the beginning.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast