“Was the American Revolution a Civil War?” and Other Thorny Questions about the Nation’s Founding

Us against the redcoats. That's how we often think of the American Revolution. In Ken Burns’ latest film, scheduled to drop later this month on PBS, the acclaimed documentarian takes on that simplistic notion of the nation's founding and many others. The revolution was actually a civil war, Burns says, one that pitted Americans, including indigenous and Black folk, against each other as much as the British.

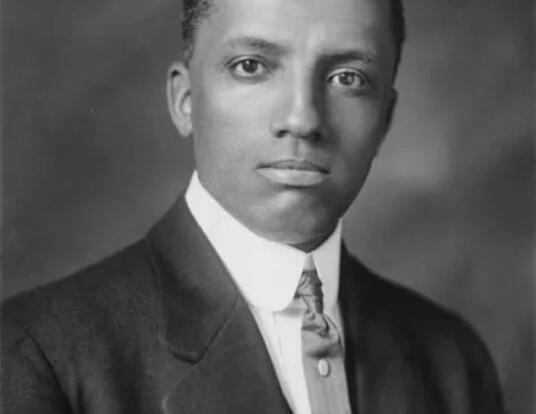

So, what were the divisions among the inhabitants of the British colonies and their neighbors? How did they flare into war? How did a fledgling nation with no central government or standing army defeat the world’s largest empire? And what were the contributions of indigenous and Black people and women? Philip C. Mead, PhD ’12, former chief historian and head curator of the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia weighs in.

We often think of the American Revolution as us against the British. But a significant percentage of the colonists were loyalists. So to what extent was the conflict really a civil war? And what was the argument between people who considered themselves English citizens, and what did it have to do with notions of natural rights?

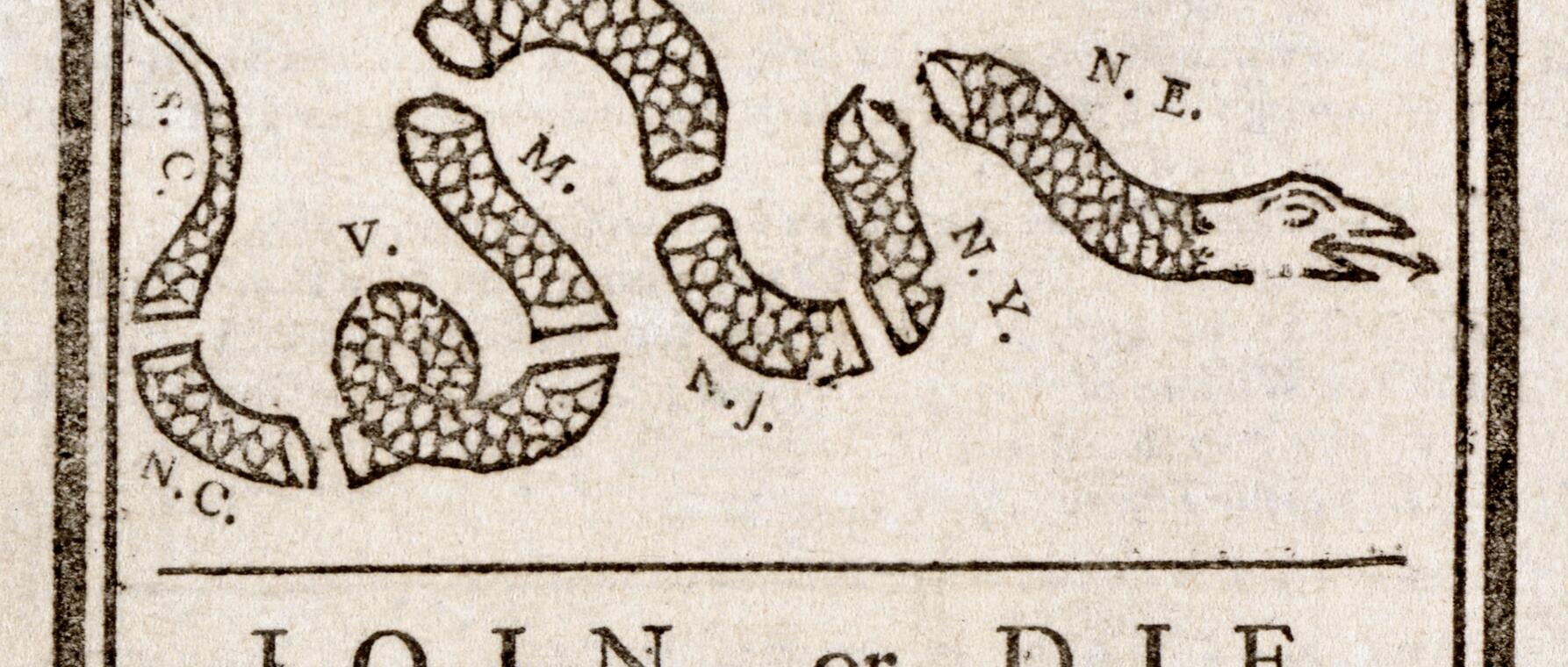

You have what Franklin called a China vase with cracks forming in it in the 1760s, where there are these divisions of interest, culture, and aspiration within the Crown’s realm in North America. So what do loyalists, what do those who remain loyal to the Crown, want? How do they see themselves in the early revolutionary years and through the Revolution?

Depends on which loyalists you’re talking about and what their alignments are. In terms of Native people, they are defending their ground and their sovereignty in many cases. And if they see the Crown as a greater ally in that effort, then they’re going to be more likely to join the Crown effort. And that’s what happened with the majority of Native American communities. The people of African descent are fighting against enslavement in many cases.

And again, which route, which ally seems the best for that, is going to attract them. There are some who join the British war effort, and some who join the Congressional Revolutionary War efforts. For the people in the English colonies, which, by the way, are geographically complex as well, 75,000 people in Pennsylvania in 1776 were primarily German speakers.

There’s a variety of motivations and attitudes, but I think there’s a distrust of this new form of government. What is this going to be? There’s no central constitution for it. The British at least have a long tradition. It’s a tradition widely celebrated throughout the Atlantic world by people like Montesquieu in his Spirit of the Laws that represent what they called the British Constitution, which is not a written constitution but is essentially the accumulated laws and traditions of British governance as the ideal form of government.

It is not ideal in some platonic sense—that if you could invent, if all humans were saints and the world was heaven, you might have a pure democracy—but in light of what human history tells us about the weaknesses of human beings, their avarice, their greed, their hate for each other, for the Calvinists in New England, their original sin, their lack of grace, the form that evolved in England was as good as one could hope for.

And so there was a lot of skepticism about the idea of overthrowing that. And the behavior of the revolutionaries through much of the conflict, both before the Revolutionary War and the war itself, didn’t do a lot to reassure many people. So there were a lot of attacks on individuals, on their property, and their persons, both before the war and during the war. And that only tended to escalate as the divisions and animosities grew through armed conflict.

We’re in a time right now where there’s a lot of polarization and divisiveness. Was that really baked in from the beginning because of the diversity of interests and backgrounds of folks who were always in this country?

It’s a really good question, and it’s a strength of what becomes the United States, that there is this diversity, for certain. I think, for example, of Jefferson’s statute on religious freedom, which he proposed as an alteration to the laws of Virginia in 1779 to update them for republican governance and eliminate monarchical elements, but wasn’t adopted in Virginia until 1786.

I think that democracy is difficult. It’s always messy. It’s always challenging. Therefore, when you have so many different interests, so many different communities, it is probably all the more so.

It is a product of the diversity of Americans. Religiously, there is no way to form a stable religious establishment that will be satisfying to all Americans. And so there’s this tremendous contribution to the politics of the Enlightenment coming out of Virginia through Jefferson. I think that’s a testament to the value of American diversity for the progress of democracy and of the Enlightenment.

I think that democracy is difficult. It’s always messy. It’s always challenging. Therefore, when you have so many different interests, so many different communities, it is probably all the more so.

You know, you mentioned the Enlightenment here. That was kind of a second part of the question that I had for you. In the Declaration of Independence and during the American Revolution, what’s new under the sun in terms of notions of natural rights?

Well, the Revolution is important in part because of when it happened. It’s in conversation with these lofty Enlightenment principles that had been baking and stirring, and evolving since the seventeenth century at least. So the Americans are trying to apply those in real time amidst a war against really the most powerful European empire. And if necessity is the mother of invention, there are a lot of things being invented.

So I think one of the greatest contributions of the Revolution to Enlightenment politics is the notion that a written constitution is a prerequisite for new sovereignty. These written constitutions are essentially created to both delineate the powers of governance in a clear way, in a concise way, for the populace at large to absorb and therefore be able to participate in—a watershed.

In 1776, the only colonies that don’t write new state constitutions during the revolutionary period, during the Revolutionary War, are Connecticut and Rhode Island, and it’s only because their colonial charters were so close to republican forms of government that they felt they didn’t need it. Rhode Island, interestingly, has this postscript of that with this Dorr Rebellion in 1850, where the populace at large—tens of thousands of people—gather and elect themselves a constitutional convention to try to establish broader suffrage, their argument being it had never properly happened.

And so there are echoes of this major innovation even among the Americans who don’t embrace it all initially. I think also the Declaration of Independence—David Armitage’s book argues that it’s the first true declaration of independence of new sovereignty in the history of the world—and its language shows up in over one hundred new declarations later, all the way through to the twenty-first century, which is in large part the subject of the exhibit I just worked on at the Museum of the American Revolution, The Declaration’s Journey.

I think that the Revolution benefits again—getting back to diversity—from the variety of beliefs that are circulating alongside the Enlightenment. Somebody like Jefferson is really, I think, echoing the Scottish moral philosophers of the 1740s in his real belief that human beings are fundamentally good and therefore it’s their bad, their social interventions that are in their way. Those social interventions would be outward—he would describe this as government—in their way. There’s something wrong with the way the constitutions are structured. And if we could just free people of that, you would find that their natural affections would form a bond that would almost not rely on governance.

And so love essentially would take over. And it’s very interesting—you see this even in military manuals of the Continental Army. There’s this emphasis on the love of the men for each other. The sergeant major must love his men, von Steuben says. There’s this sense that the Revolution was a departure from a stern, command-brutal world, creating a lofty, liberated, affectionate world.

It’s reflected in the material culture of the period. You go from—and this is over a long arc, but it’s the spread of these ideas, of which Jefferson is in some ways a symptom rather than just a cause—you see tombstones go from death’s heads with skull and crossbones to cherubs and then willow trees. And there’s this move from the dark to the optimistic, from the hellish to the heavenly, and ultimately to the naturalistic and romantic.

So there’s a lot that’s new to that. But there are also people like Adams who are devoted to this Calvinist idea that people are basically bad and that, therefore, we can’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. We can’t have a pure democracy because it’ll become anarchy. And so we need some sort of system that’s going to embrace these Enlightenment innovations but also apply the inherited wisdom of the ages.

You were just talking about the different attitudes of Jefferson and Adams, and you talked about Adams’s attitude toward democracy. Did the leaders of the Revolution distinguish between the terms democracy and republic? Were those concepts interchangeable to them, and what did those terms even mean to them? And how central were those ideas to what they were fighting for?

A republic is a form of government that includes representation that tries to take advantage of people’s best inclinations by organizing a constitution that essentially neutralizes their worst ones or limits them. And that includes the dangers of democracy.

So what you kind of have to do is go back from, rather than looking at them through our lens and our question of what is democracy, look at what thinking politicians would have read about democracy when the revolutionaries were young, and how they understood that word. Principally, a democracy is a term that they would have included—or that they often included—in what was called the “mixed government” sense of proper constitutional organization.

So, a mixed government is like checks and balances in that it has different powers for different institutions of government. But unlike checks and balances, which is kind of an invention of the American Revolution, mixed government assumes that each of those institutions is the embodiment of a social order, of part of the society. And one of those parts is the democracy—this is the sort of “the many,” as the mixed government would call it; it’s the bulk of the people.

Another element is the aristocracy. Those are the titled nobility in Europe, the gentry in America. And then the third is the monarch, or “the one.” So there’s the one, the few, and the many.

Adams, in particular, was devoted to this idea, and in his A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of 1787, he basically produced example after example after example of how every society had these divisions. And every society, every constitution or form of system of government, that failed to provide each one of those social states with an institution of government and powers of government to protect itself, ended up with a war between them.

And so if you didn’t design your society right, each one of these groups would become its worst version. If you designed it correctly, they would become the best version. Each one had a democracy, aristocracy, and monarchy. Each had a virtue and a vice. Democracy—the people—were honest. As Adams said in 1776, “a democratic despotism is a contradiction in terms.” You cannot have the people in their own way; they will do their best for themselves, the bulk of the people. But they’re disordered; they don’t necessarily know their best interest, and without controls, they become anarchical.

The aristocracy—their benefit was wisdom. They were generally very invested in stability because of their wealth. They studied how to achieve that. They usually had good educations because they had the leisure to get them, and so they were valuable as a check and advice on both democracy and monarchy. But they could become an oligarchy—that was the negative version of an aristocracy—where they, in the way this typically would happen, became concerned that one or the other, the monarchy or the democracy, were going to take away their wealth or their privileges.

And so to defend them, they became corrupt and turned into an oligarchy trying to secure too much power. And the monarchy—the one—the inherited position, usually was powerful. That was its best value, that it could act quickly. It didn’t need consultation and deliberation; it could just move. This is why the military is in the hands of the monarch in England, other than the power of the purse. And in the federal Constitution, the president, as the commander in chief of the army, you need them to be able to attack or make peace, to initiate that, you know. But the danger is they could become tyrannical. So they use their decisiveness and their individual power to bulldoze the powers of the other two estates.

So they saw democracy as an essential part of good governance, but as a danger if it got out of control, just like the other two estates. And so, you know, what’s interesting about the Revolution—what’s the problem for them—is that they don’t have an aristocracy or a monarchy once they’ve declared independence. They work hard to try to figure out how to create that mixed government system without those things. And that’s where we get checks and balances.

The struggle of the Revolutionary War is often portrayed as between this well-trained army of professional soldiers—mainly the British—and a bunch of country farmers. I’m wondering if we oversell that David versus Goliath picture of the war itself. And if not, what were the main factors that enabled untrained, poorly equipped colonial troops to defeat Europe’s largest empire?

It’s an eight-year war, and by the end, the Continental Army is as good as the British Army. Washington’s troops are as well equipped, as well trained, as well officered as the British, well fortified, well engineered, and they are very proud of that.

In fact, one of the exhibits we did at the museum was about a watercolor that I found at auction of the American encampment at Plank’s Point, which had bowers across each of the fronts of the regiments. Washington’s tent was on a hill with a dining bower in front of it. They had drills demonstrating their battle prowess, and that was designed for the French army audience that had joined the United States in 1778. But after Yorktown in 1781, they were considering leaving the continent and then going elsewhere to fight, and Washington wanted to show them, “Hey, we’re still winners here. We’re still on it.” And they really were.

So we do oversell that narrative to some extent. Now, the achievement of putting together an army like that can’t be oversold. I mean, they start this conflict with no centralized form of governance. There’s a First Continental Congress before the war, but they are essentially no different than the Albany Congress or the Stamp Act Congress, which are predecessors that have no power, that are just a diplomatic détente among the colonies.

You’ve got no army, no navy, no currency. The colonies have been under some mercantile controls in the development of industry. So they have nothing like what Bristol in England is becoming. The population of the mainland colonies is less than a quarter of what’s in England, and they’re trying to take on this massive empire. Other than when the Bourbon navies—the French and Spanish—combine, the British navy by itself is the largest navy in the world. And this is a coastline defense proposition across the Atlantic.

It’s an eight-year war, and by the end, the Continental Army is as good as the British Army. Washington’s troops are as well equipped, as well trained, as well officered as the British, well fortified, well engineered, and they are very proud of that.

So, what the Americans accomplished in that mobilization is stunning. And it is true that in the beginning of the war, 90 percent of Americans were farmers or lived on farms, approximately. So they are, in a sense, embattled farmers, especially at the beginning.

At the end of the war, because of the tradition that the army and navy were controlled by the monarch, and Americans’ fear of the rise and return of a monarch or tyrant, they essentially just completely dissolved the military, having performed and achieved so much. They had to completely reconstitute it later. But the army was a citizen-soldier army in that they really expected to go home when the war was over—and they did.

Although it becomes a professional fighting force, it’s not professional in the sense that you have truly career soldiers or regiments. In England, regimental bonds and identity last across generations—if you’re a royal fusilier, it’s part of your identity. It’s like they say, “Once a Marine, always a Marine.” But in the Revolution, you know, the Third Massachusetts Regiment doesn’t have that kind of longevity expectation. So they have to form these bonds another way—some of them through their civilian connections and their hopes for the long term of the United States, the idealism that the Declaration of Independence and the state constitutions represent. So, we both oversell it and undersell it to some extent.

In your response to my first question, when you were talking about the diversity of the country, you spoke a little bit about Black and Indigenous folks being an important part of the Revolution as well. Women were as well. I guess, first of all, it would be interesting to know what the Black and Indigenous population of the country was at the time of the Revolutionary War. Do we know that? And then, if you can, talk a little bit about some of the most common misperceptions we have about the roles that women, Black, and Indigenous people played in the Revolution and how we ought to understand their contributions.

Well, the best numbers are from the 1790 census, which shows about 450,000 people of African descent. It’s hard to say exactly, reading back to 1776, how accurate that number is, but we can use it as a rough approximation. That’s in a population of about three million overall in what becomes the United States.

There are a lot of challenges with getting good statistics on the populations of Indigenous people, but I think often there’s a number of about a quarter million used for the area east of the Mississippi. So the colonies—the United States—had very large, very powerful populations of both groups. Of course, most of the people of African descent, their power is profoundly circumscribed by most of them being enslaved.

But you see them taking agency in their actions during the Revolutionary War. I think one of the misconceptions is that this is a sort of non-important population—that they’re maybe laboring but not agents of change. That is absolutely not the case.

For example, Lord Dunmore, who famously proclaimed in 1775 in Virginia that he would emancipate people of African descent who were enslaved to rebel masters and who joined the Crown forces, did that. He formed what he called the Ethiopian Regiment. There were echoes of that in a subsequent promise in 1779 by General Clinton of the British Army, called the Philipsburg Proclamation. But when Dunmore went to South Carolina trying to form a Black regiment there, he was run out on a rail.

He was fired from his role in Virginia largely by parliamentary interests, largely because they saw him as too radical. The sugar interests, the plantation interests of members of Parliament at that stage, were threatened, if anything, by the separation of their interests from those of the Lower South colonists of North America. The planters worked as a political bloc, and once you divided that bloc, both ends were weakened.

I think one of the misconceptions is that [people of African descent are] a sort of non-important population—that they’re maybe laboring but not agents of change. That is absolutely not the case.

So strategically, on the ground, enslaved people and free Black people had a lot of tactical power, but they were not in the midst of a clear choice about which side was actually going to benefit them the most.

In terms of women’s roles in the Revolution, that population is a little easier demographically to chart—it’s about half, as it usually is. Their contributions are broad and vast and essential. The armies—both armies—had women in them. This is often misunderstood because later wars don’t necessarily have that same dynamic. The primary reason being that before the railroads, the “behind the lines” is the same as the front lines, usually.

So you have to have all of the noncombat services that would normally be, like in the Civil War, back in D.C., actually be in Petersburg—or the counterpart of that. In the Revolution, they need to be at the front. As a result, they’re often taking fire and being exposed to combat, in some cases actually grabbing guns or ramrods for cannon or what have you, and fighting.

It’s a war that, as a result of those kinds of combat and the losses of men—either temporarily or through death—sees women take on political and economic roles that weren’t normative. There was a precedent for this that Laurel Thatcher Ulrich writes about in Good Wives—the “deputy husbands”—where women sort of step into the role of husband when the husband’s away. But in the case of New Jersey in the Revolution, which had the most incidents of combat of any state, it’s so despoiled and ravaged and disrupted by war that women have to take on, in many cases, more permanent political, administrative, and economic roles.

So I think it’s no coincidence that New Jersey has thirty years of women’s suffrage between 1776 and 1807, which we did an exhibit about at the Museum of the American Revolution called When Women Lost the Vote, about that period and the ultimate loss of it. But a lot of those women who are voting are essentially veterans of combat in their backyards.

Native American groups and Indigenous groups in the Revolutionary War itself, as I mentioned earlier, weigh this conflict and see which side is most likely to be a good ally for their goals. There are Native American volunteers and participants in both the Continental Army and on the British side. So there are people who are individually joining and engaging who live within the governments of the colonies. But as groups, as nations, it’s a tough call.

Most Native American groups, most Indigenous groups, decide to side with the British. Most of them remain out of it—stay out of it—until 1777. Then what happens is that after the battles of Trenton and Princeton prove that Washington’s army has some durability and that this thing isn’t going to end quickly, the British send diplomats out to Native communities saying, “Prior to this, we asked you to stay out of it. Now we need your loyalty, or you’re going to be an enemy.”

And so they’re essentially pressed to choose sides, and they vote in most cases, which is the way governance happens in most Indigenous communities in North America. There’s a consensus form of governance derived in part from deliberation and voting. But some communities are divided.

If you go to the exhibit that we just did at the Museum of the American Revolution on the Declaration’s influence, you see its language being adopted . . . [by representatives] from the Mashpee Indians of Cape Cod and the Cherokee, to the women’s suffrage movement, to Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., the gay rights movement, the environmental movement, and the workers’ rights movements. If we morally debunk that era, we lose that language, and we lose a lot of the fuel that has produced, I think, the world we prefer to live in.

The famed Iroquois Confederacy divided, where the Oneida and Tuscarora joined the United States. The United States recognized the Oneida as an ally. They attacked the Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga, who joined the British. But the Revolution ultimately is very tragic for Indigenous people. Even the Oneida, who joined the United States as their allies, lose their territory. It’s essentially traded away by the state of New York on the grounds that, well, that was a treaty made with the United States, not with the state of New York.

Ray Halbritter, who is the head of the Oneida Nation, which was very involved in the American Revolution, gives a really heartbreaking narrative of his own memory—the memory in the community of the Revolution—and how his grandmother always made sure that, as a condition of their alliance, they would get a piece of cloth every year. And she said, “No matter what, go to D.C. and get that cloth every year, because it’s the way of ensuring that we are actively acknowledged as part of this treaty. Eventually, we will get our lands back.”

At a time when, in our country, many on the left and the right believe that democracy and our way of government or system are existentially threatened, should we look to the founders and the leaders of the American Revolution, or repudiate them, in order to get our bearings?

Well, I think we should look to the revolutionary generation. That would be a broader, more diverse group of people than the founders, so-called. It would include them. I think that now is a time when we are facing similar conflicts and similar disruption, that we should look to them. We don’t need angels for models, because that’s not relevant. We’re not angels. And we need history that’s going to be realistic about the challenges of democracy.

So understanding the Revolution as a whole—with nuance and complexity, including not ignoring the inspiring parts, the aspirational statements, the fact that women did have the vote for thirty years, the fact that there were abolition acts, gradually or otherwise—those are major things in world history. But also, the dark and the challenges of that are more relevant than ever.

And I think we somewhat impoverish our ability to see progress and change if we totally disown things like the Declaration of Independence. If you go to the exhibit that we just did at the Museum of the American Revolution on the Declaration’s influence, you see its language being adopted all over the world, but also by representatives from all of the groups we’re talking about—from the Mashpee Indians of Cape Cod and the Cherokee, to the women’s suffrage movement, to Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., the gay rights movement, the environmental movement, and the workers’ rights movements.

If we morally debunk that era, we lose that language, and we lose a lot of the fuel that has produced, I think, the world we prefer to live in.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast