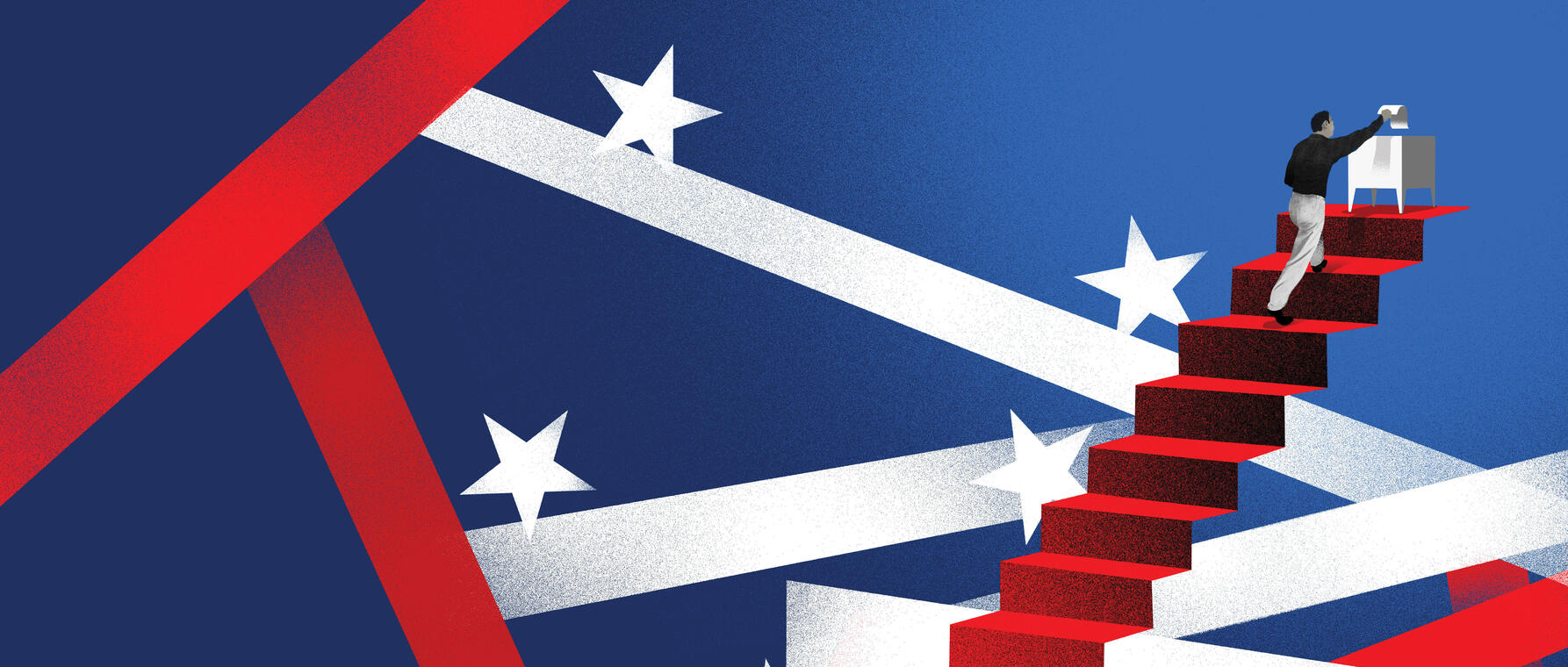

Voting Rights, Climate, and the Most Important Election in US History

As states around the country face off in a contest of gerrymandering, what is the future of voting rights in the United States? Will the Supreme Court nullify what’s left of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965? How will accelerating climate change affect US politics? And what might happen in the all-important election of 2028?

Harvard's Frank G. Thomson Professor of Government Stephen Ansolabehere, PhD '89, an expert in public opinion and elections and a consultant for the CBS News Election Decision Desk, recently joined Dean Emma Dench of the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences to address these and other questions about elections, energy, and the public mood. The discussion was hosted by the Harvard Club of Chicago. (Please note: Some questions for Professor Ansolabehere were submitted by members of the audience at the event.)

This transcript has been edited for correctness and clarity.

Dean Emma Dench: So, getting started, Steve, it is absolutely great to be talking to you again. Steve and I have had a few conversations, mainly about calling elections. It feels like that was another world. So a lot’s happened, and we’re going to see if we might touch on three sort of main clusters of topics.

One would be very, very topical, in the news very much today. I thought we might start with voting rights. I know we both really, really want to get to what you’re up to—what on earth you’re up to—at the Salata Institute about thinking about climate change, because there are some very exciting things going on there. And then, where we have time, we might hopefully touch on calling elections and predicting outcomes of elections.

What do you think? I think that that will do. So, plunging in with voting rights very, very much in the news right now, with the Supreme Court beginning to hear the case from Louisiana. And I guess there’s everything that that case on voting rights and districting brings up, and also the likely consequences. So we might get you both as analyst and as predictor of what effect that any ruling might have. Can we start there?

Professor Stephen Ansolabehere: Right. So there’s a case before the Court right now called Callais, the name of one of the plaintiffs, and it’s challenging Louisiana’s congressional district map and the configuration of a district that was created to comply with what’s called Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Section 2 says if there are enough minority voters of a single group—like all Black or all Hispanic—and they vote cohesively together, then you must create a district in which they can have representation.

So, Louisiana drew such a district following on some earlier lawsuits. Plaintiffs have decided to challenge the Voting Rights Act to see if Section 2 will effectively be either scaled back significantly or thrown out altogether. Right now, there’s another case in Texas that is not getting any press. That’s under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which is equal protection.

And if Section 2 is struck down, there’s the threat that many states will then go out and try to redraw their maps to get rid of mainly Black districts in the South and a few Hispanic districts. The problem then will become whether the courts will step in and say, “No, no, no, you can’t do that,” because that’s actually intentional discrimination against Blacks and Hispanics.

So, this is going to take a long time to play out. It’ll probably take the rest of the decade to play out, but it’ll be fascinating to watch. And it does go to the heart of what we think of as equality, equal protection, and the right to vote. This is where the right to vote really resides in the United States.

Dench: That’s so interesting. I wonder if you could give us a bit of historical perspective. As far as I understand it and remember—I’m always a bit of a learner when it comes to American politics, let’s say. I’m pretty humble about what I don’t know. But my understanding is that the Voting Rights Act was formulated under a very different context. What’s changed?

Ansolabehere: Yeah. So, the Voting Rights Act was written in 1965, and it prohibited devices to discriminate against the access to the vote. It was really aimed at getting rid of literacy tests, poll taxes, things like that. It didn’t actually mention redistricting originally. That kind of came up after the 1972 redistricting round, and eventually the courts allowed it. But it was always a big question all the way into the early 1980s.

And then Congress amended the Voting Rights Act in the 1980s to cover redistricting, and that’s been central to the Voting Rights Act’s application for the protection of voting rights. There was a famous case in the 1980s called Thornburg v. Gingles, and in that case, they actually specified how social scientists could contribute to understanding, for the courts, whether the minority voters were sufficiently cohesive, whether there was enough concentration of minority population, and so forth.

So, someone like me will be enlisted by plaintiffs or a state to weigh in on those questions. Since 2011, I’ve been pretty deeply involved in several states’ litigation over this area. And it has been a tussle and a back-and-forth. I would say that the thing that’s changed in our society that the courts have not been able to figure out is that we no longer live in the world of 1965. The world of 1965 and the problems the Voting Rights Act went after were very much Black-and-white Southern politics.

And we now live in this multiracial society, and there’s no guidance from the Voting Rights Act about what do you do with a place like Houston, where you have Blacks and Vietnamese and Hispanics all living close to each other, voting similarly. Well, do they get a district? Do they not get a district? What does the district look like? Is it supposed to be Hispanic? What is it? And the courts are kind of stymied. And I think ultimately Congress needs to weigh in and rewrite the Voting Rights Act to clarify these things. The courts have been kind of befuddled by what to do, frankly. But it is a just profound change in our society. Just how profound that change is: Texas is no longer a majority white state. What do you do? What does it mean if Texas is no longer majority white, but most of the districts are majority white? That is the world we are facing now, and the courts have been the place where all this has been worked out, but it really needs to be worked out in Congress.

And Congress has kind of kicked the can down the road. And I think what’s happening is that John Roberts in particular doesn’t want to deal with this anymore, and he wants to kick it back to Congress.

We now live in this multiracial society, and there’s no guidance from the Voting Rights Act about what do you do with a place like Houston, where you have Blacks and Vietnamese and Hispanics all living close to each other, voting similarly. Well, do they get a district? Do they not get a district?

—Stephen Ansolabehere

Dench: Any sort of best predictions on what—if it’s not just too soon—on what might happen?

Ansolabehere: I don’t know, because there’s this looming question of the Fourteenth Amendment. And because of the Voting Rights Act, there’s very little litigation on the Fourteenth Amendment, actually, because things would get covered by the Voting Rights Act and everything would be figured out that way. So there’s almost no historical case law on what the Fourteenth Amendment compels in these cases.

Dench: And thinking about voting rights more generally, we hear a lot about voter fraud. In terms of the population at large, how big a problem do people think it is, and how big a problem is it actually?

Ansolabehere: The framework is this trade-off between access to the vote, like making it easier for people to vote, and protecting against fraudulent votes. And the fraudulent votes can be of a couple different types. They can be people voting who legally should not be allowed to vote, or they could be people who are legally allowed to vote but doing something unusual, like selling their vote.

Or they could be people interfering with someone else’s right to vote and therefore creating a sort of vote fraud, such as hacking into the electoral system and destroying ballots. Internet voting is something that the Defense Department has been experimenting with for a long time, because if you’re US military personnel and you’re stationed in Iraq or somewhere, and it’s not possible for you to get a mail ballot in on time, certified and signed by the postmaster or whoever else would countersign, then you need some way of submitting a ballot.

And so the US military has been very keen to have internet voting. The problem is, internet voting is so hackable. It’s so hackable, and you can’t certify it. So it’s not like a bank transaction where you, the customer, have a receipt. We can’t give you a receipt for voting, because if we gave you a receipt for voting, you could sell your receipt, and that would be another kind of vote fraud.

So this is the problem everybody’s trying to weigh. And the really sticky part about vote fraud is that if it’s a very close election, you don’t need a lot to disrupt it, right? Imagine if in 2000 in Florida, which was separated by 500 votes, you had an appreciable amount of demonstrable vote fraud. Like, what would you do? Some states have rules.

So one of the cases I was involved with involved the Ninth Congressional District in North Carolina a few elections back, and somebody had gone through rural areas, solicited people, figured out who was going to get an absentee ballot, and then offered to help them. And if that person didn’t like the way that person was going to vote, they later destroyed the ballot and never mailed it in. And we were able to document that the amount of ballots destroyed was actually bigger than the margin by which the candidate won.

And so they actually had a new congressional election. They had a whole new election in that state. But not every state has the laws clarified about what you would do. And in something like a presidential election, that could be quite incendiary.

Dench: Fascinating. The questions are coming in fast and furious, and they’re very good ones. So we will start our weaving. One very good listener in the audience remarks that for us sitting back, when we see, it can appear that in each state the dominant party, what they’re up to is gerrymandering and disenfranchising voters of the other party.

I think I can definitely see that going on, and [the questioner] wonders about a simple algorithmic approach that can sort all this out and kind of take the heat out of it, I’m guessing.

Ansolabehere: So political scientists have developed many standards, but every one of those standards has failed to meet a very specific test in the courts. And that test is: Would the Fourteenth Amendment—would equal protection—lead you to this standard? So we come at it from the other way, which is what looks like a fair allocation, and they’re coming at it from what does equal protection mean, and would it lead to that. And there was a case out of Wisconsin in the last decade where somebody actually got a standard accepted by the federal courts, but the Supreme Court struck it down and said, “That’s not—we don’t see the connection to the Fourteenth Amendment.” So that’s still out there as a live question. And that’s the challenge.

Like, can you start with the Fourteenth Amendment and arrive at an answer, because that’s what the principle would lead you to, as opposed to can you start with some social science theory over here and walk up to it? And that’s, I think, where we as a field are sort of stymied.

Dench: So—and I think I have another question that asks you to double down a little bit on what you’ve just said, asking about what is at the heart of the Voting Rights Act and what is its essential universal value.

Ansolabehere: The Voting Rights Act, at its heart, was trying to get rid of an old system of discrimination—mainly in the US South, some other states were really the focus of the Voting Rights Act. And again, there’s this very live question, which I think this case and a prior case in Shelby County raised, which is whether or not the Voting Rights Act is something you would pass today.

So I think that’s the question. If we started anew, would we pass the same Voting Rights Act, or would we do something different? And I think that’s the question that we’re going to have after this year is over at the Supreme Court.

Dench: There’s a cluster of questions—and please forgive me if I don’t give you a whole question, but I’m trying to be efficient and effective. There’s a lot of interest in the room, essentially, in kinds of manipulation of votes. Just giving you some brief examples, the idea of Russian interference—that’s on some of the guests’ minds. AI is on some of the guests’ minds. Also the influence of kind of mega non-eco companies, things like that. And I guess [they’re] asking you to evaluate how much these interventions are manipulating the votes, and then what we would do about them.

Ansolabehere: So there are a few interesting ways in which you could manipulate elections, and there are some ways in which people think you can manipulate elections, but actually it’s really hard. The first principle of the US election system is: it’s horribly disorganized and decentralized, and it’s run by amateurs. Right? Like, who works the precinct on election day? Because you’re basically giving your day, right? You get paid maybe a nominal amount at most. But you know, there are, I don’t know how many volunteers, like a million volunteers on election day who run our elections, and they work all day and they’re not really paid much.

And many of them, because of the state laws, because you’re afraid of somebody doing something weird, are not allowed to leave the polling place, right? You’ve got to stay there all day. You don’t want shifts coming in because you have to have the chain of command of, like, who actually is in charge of these ballots. But that turns out to be a real strength of the US system, because there are all these people watching it who are basically private citizens who are there because they care about it.

And it’s highly decentralized. So if you hacked this precinct over here, you couldn’t hack this precinct over here. It’s really hard to do something in a coordinated fashion in the US system. So the thing we all complain about—about, like, it’s volunteers, decentralized, they don’t spend much money—this actually turns out to protect it against, you know, some concerted effort. Like after the 2020 election, there were a lot of allegations about—and after the 2000 election and the 2004 election, there were a lot of allegations about—hacking voting machines.

Near as we can tell, none of this is or could be true, and it’s been looked at really closely. So there probably needs to be better national standards about what the voting equipment ought to be, what it ought to look like, and how it ought to be managed. But in 2000, there were none, like none, zero. And after the 2000 election, a lot of things were put in place to have something that was a more sensible national standard about security of software, about inspection of software, and so forth.

The thing we all complain about [the voting system]—about, like, it’s volunteers, decentralized, they don’t spend much money—this actually turns out to protect it against, you know, some concerted effort [to manipulate it].

—Stephen Ansolabehere

So I think that protected us from what could have gone wrong in 2020. The other piece of the system is the registration system. This was pretty badly managed in 2000, and a lot was done to improve that. The concern now is that because most of that is now electronically managed, somebody could get in and hack and disrupt it.

And so that’s, like, the real fear of a hack: it would be a hack that disrupts the registration system. The states, because it’s done at a state level now, are pretty good about maintaining backups and so forth. So even if there was a hack on election day, there would be a backup present in every state, so that wouldn’t probably disrupt things.

And then the final thing, where there is probably a more real concern, is the flow of information and communication. And that was 2016. The Russia hack was not a hack of a machine. It was not a hack of registration lists. It was a hack of the internet, the flow of social media and the capture of social media by Russia Today.

And that’s a tougher one. That’s like, you have to be a pretty savvy consumer to know that RT means Russia Today, and that your news feed is not coming from where you think your news feed’s coming from. And that’s, I think, the biggest concern that people in my discipline have about the hackability of elections: the hackability of the information flows.

Dench: Is there any way of protecting against that? Does education—and what are the safeguards?

Ansolabehere: Well, one thing that helps is we’re all very partisan.

So, we had a meeting of the political analytics group. The New York Times and CNN and Fox and all the news media participated, as did a lot of the political consulting firms and so forth. And we had a panel on forecasting and postmortem. And the question I put to the panel was, “It’s 2028. What’s your postmortem?” And all three of the panelists said basically they were afraid of the AI hack, where you just create AI bots that totally simulate whatever you want the other candidate to have mistakenly said, so that our information flows online becomes completely untrustworthy. I think that may be the real threat that we see in the next election: what happens when the internet is no longer a good provider of information because we just can’t trust what’s coming to us?

Dench: I would really like to talk to you a little bit about your work with the Salata Institute on climate change, and starting off very generally with a couple of questions. What are you, as a political scientist, doing in the climate change realm? What is your contribution? And more generally, what are the people at the Salata up to? And is there work to do when we’re hearing that there’s investment in climate change issues?

Ansolabehere: I got started working on energy issues in 2001 when I was at MIT, and my colleague Paul Joskow, who’s an economist at MIT, asked me to do a survey for a study that he and Ernie Moniz, who later became secretary of energy, and John Deutch were doing, and their study was on nuclear power. And the question they were posing to frame the study was: Given climate change, what should be done with nuclear power in the United States? It was a very good question. And Paul said to me, “John and Ernie have a plan to build 400 nuclear power plants.” There are 100. “And [former White House chiefs of staff] John Podesta and John Sununu, who are on the advisory group for this study, think that John and Ernie are putting the cart before the horse, and they want somebody to do a survey.”

And I was like, I don’t need to do the survey to tell you how people are going to react to 400 new nuclear power plants being built in the United States. But I did a survey, and then they just kind of brought me into their group. So this has always been like a second thing I’ve worked on, and I continued to work on it.

And then when Ernie came out of the administration, he said, “We’ve been going about this all wrong,” because he was studying fuel cycles. The Department of Energy’s organization is like: there’s a nuclear program, there’s a coal program, there’s a gas program. “So it’s not about fuel cycles. It’s about people.” And Ernie’s a physicist and John’s a chemist, and John’s like, “Yeah, we’re sociologists.”

So I brought in Jason Beckfield from [Harvard’s Department of Sociology] and Dustin Tingley from [Harvard’s Department of Government], and the three of us, together with friends at Harvard Law School, started working on what should be done differently about the way the United States develops its energy systems, because these are really complicated systems that nobody wants to think about and nobody should have to think about.

It’s the opposite of elections, right? It’s like this subterranean thing, and you just don’t want to worry about how much it costs when you turn on the switch. And we assume that it works. But we’re starting to hit some stressors. And the Salata Institute was set up around that set of problems: How do we, as a national society, and how do we, as a global society, deal with the biggest stressors—climate change?

But there are also these other stressors that are coming, and the current one is: for the past 30 to 40 years, electricity in the United States has grown at the rate of 1 percent—electricity use and development. So that doesn’t take a lot of planning, right? You don’t have to build a lot of stuff. You can get rid of some stuff and get rid of some old coal plants and build, you know, occasionally build a nice, new, efficient gas plant.

But with AI, it’s now going to grow like 5 percent a year. And we have to build stuff. And as soon as you have to build stuff, then you have to put power lines through people’s communities, you have to build gas pipelines, and you have to build nuclear power plants. And these are things that people really hate. Like, they really hate this stuff.

We have one survey question we started fielding, which was, “Here’s a list of infrastructure-like decisions, and what would be OK for the use of eminent domain?” Because most of this stuff ultimately has to use eminent domain, where the government actually forcibly buys somebody’s property. And people are happy using eminent domain for getting rid of a blighted building or building a park.

They’re not so happy about using eminent domain for building a power line, a pipeline, or an energy facility. So these are things that really anger people, and that becomes the brake. So the whole system and our ability to meet these challenges, like climate change, high demand, and so forth, depends on our ability as a nation to engage with people so that we do this in a sensible way, so that people’s opposition isn’t forever stopping us from doing what we could achieve.

Dench: This is amazing. So I’d like to hear a bit more about that. Building on that, how do you persuade the general public that climate change is a thing, and especially now, especially when many people have the perception that they’re not personally experiencing it? “Oh, we had a hot summer, then we had a cold summer, and it’s not a thing.”

Ansolabehere: Yeah. So all those things are true. It turns out that the percentage of people who think that climate change is not real is tiny—it’s like 5 percent. Climate deniers are very rare. There are people who think it’s not something we need to do a lot about right now. There are people who think that it’s not present.

Dench: And how big is that, roughly?

Ansolabehere: The concern has been growing. But whether or not that concern drives you to take drastic action is a different matter. People increasingly see, like, well, the number one contributor is China. China should take the lead on this. Mike Greenstone, here at the University of Chicag,o has been one of the leaders in calculating the social cost of carbon.

And by his calculations, it’s not a big dollar value today because most of the harm is in the future. So the net-present value, once you discount through our discount rate that we usually use in investment, means that the amount that you’d be willing to pay to avoid those harms in the future is actually fairly modest. And that means that it’s really hard to justify, from a cost–benefit analysis perspective, doing more.

Yeah, that’s a tough sell. So that perception isn’t actually wrong from that perspective. But now is the time to do the cheap things. Right? So it’s a bit of a conundrum: when you want to do things that are very cheap, it doesn’t actually pay in a net-present-value sense. But later on, when things are really bad—or in societies where it’s really tough, like India, where you can’t afford to pay all that you need to pay—those wide harms [are greater].

So Salata is organized into a set of research clusters that are working on different aspects of the problem. The cluster I’m leading looks at communities and how they’re affected by changing energy systems. So what happens is, one of the big brakes on doing things in terms of policy change is we don’t have in the United States great ways of dealing with abandoned communities.

What happens when the coal industry goes away in West Virginia, and you leave enormous social problems behind? What do you do with people? We don’t have great infrastructure for dealing with that. And when that’s a threat, those states will see it—like Louisiana, Texas, they see what will come of their state if we put a big carbon tax on. And they resist us. And it’s not irrational. It totally makes sense.

So there’s got to be some dialogue. So it’s not a matter of persuasion. It’s more a matter of engaging and kind of trying to come up with something that benefits everybody, that everybody will agree to. So it’s more like a negotiation and less of a persuasion. I think Al Gore’s approach was persuasion, and I don’t think that worked for half the population. But it didn’t work for the population that was going to put the brakes on. And they did.

Dench: Let’s get back to doom and gloom. I’d love to know a little bit about your work predicting the outcome of elections.

Ansolabehere: But that’s not doom and gloom—that’s a blast.

Dench: That’s fun. Yeah, yeah. Okay, I’ll go with you. I like the optimism. So, see, what could possibly go wrong? What are the challenges, and basically what do you draw on to try to predict the results of an election, and how stable are these?

Ansolabehere: So elections are super regular. They’re super predictable. And they move back and forth pretty steadily. And this is one of the great things—and the UK is the same way. At CBS on election night, I had been on them since I started working with them in 2006 to develop a really simple, and I think really stupid, model.

Our challenge is, like, how do we know? We’ve got polls and all this other stuff. How do we know where we’re at? So it’s 7:30 in the evening. Do we know anything? It’s 8:00. We don’t think so. It’s 8:30. Do we know anything? And the simple model is: take all of the elections where you’ve got completed returns in—so, like, Indiana closes early, part of Florida closes early, we get some North Carolina results, we get Virginia results—and then compare those to the immediate prior election for that office. So if it’s US House, compare US House; if it’s president, compare president; and measure how much movement there’s been, and then assume that that amount of movement occurs everywhere else in the United States.

That’s a pretty stupid model. Right? Like, there’s nothing special—it’s using Indiana and, you know, South Carolina to impute what happens in California. So I finally got them to start programming this on election night in 2016 and then in 2018, and it’s never been wrong by more than four seats by the end of the election night. So by about 9:00, we’ve got it done.

But there are some real regularities behind elections which make them more understandable, and the public moves back and forth in some understandable ways that actually kind of make you feel better about what people are doing when they’re voting. So, 2024: just about every group, every state, every county moved three and a half points from the Democrats to the Republicans. It was super regular.

So you look at why people moved, and it was inflation. There’s a guy at Yale named Ray Fair, and Ray has a model for forecasting elections that he trotted out in, like, 1990 or ’92. And the Fair model has worked really well, and it’s based on how much change in real personal disposable income there is—after tax—and your after-tax real income change plus the worst quarter of inflation.

And that predicts very well. And the day before the election, that predicted that the Democrats would get 49 percent of the vote. And that’s what Harris got. So it was really an economic election. The groups that shifted the most from 2020 to 2024 were Hispanics, especially Hispanic men, and Asians. But it wasn’t Blacks, it wasn’t young, it wasn’t non-college men, or any of the things you’ve heard.

So you look at the exit polls, and it’s really clear who moved. And so I thought a lot about that. What is it about Hispanic men and—now, you wouldn’t have guessed—Blacks, that they would have embraced Trump? They’re America’s working class these days. Who’s working the menial behind-the-counter jobs? It’s largely those folks. And they were really hard hit by this economy.

So then we went back and looked at the economic data. Turns out those are the groups that were hardest hit by the economy. So this was very much an economic election. And almost all of them are.

Dench: I was hearing an item on the radio—a long item—on undecided people and what were effective techniques that sway opinion. I mean, you talked about the economy, but in terms of politicians trying to put a thumb on the scale, what works?

Ansolabehere: The earliest studies of this in political science and sociology went after this question, like, you know, back in 1948, right—Truman versus Dewey. “Who won that election?” It was largely thought to be, like, a media phenomenon. I mean, they had these intensive studies of these communities, and they measured their media use and so forth.

It didn’t really move the dial that much. People very much think about their situation, their community, their culture, how it’s being affected. And that is the biggest thing that is shaping the decisions they make, which party they align with, and so forth.

Dench: Are you saying it’s profoundly local in all sorts of ways, or individual?

Ansolabehere: I think it’s individual, and the economy’s complicated. So if you ask somebody, “What’s the unemployment rate?” you’ll get different answers from different kinds of people. But it turns out those different kinds of people actually have different unemployment rates. A Black man without a college degree has a different unemployment rate than a white woman with a PhD. There are different unemployment rates, and that’s reflected in that they’re seeing different—they’re experiencing different economies, not just locally, but just which stratum they’re in in the society.

Dench: We hear a lot about the polls, and I’m just struck by how fine-tuned your analysis of different demographics and their experience was just now. But habitually, it seems the polls get things wrong. Is that right? And they’re getting worse, because who picks up the phone, who answers the door, who does random polls that pop up on your phone, and you think it might be a virus? What do you do with polls? What do you think about polls before we actually get to 9:00 p.m. on election night?

Ansolabehere: So on election night, I don’t use them. But I use them a lot in my research. So there are different polling organizations, and they approach the world differently. The best model is that the organization actually recruits people who will participate in different kinds of studies. So they’ll recruit, like, three million people, and then when they’ve got surveys, they’ll just do the surveys from those people and do them in a way that they match the general population. That protects them against bots. Bots are going to kill the industry, because there’s just no way to protect against bots. The terminology is that that’s a panel. So YouGov has a panel and so forth, and that’s a pretty good way—that’s proved to be a pretty good way—to do a survey.

The other kind of sampling is what’s called river sampling, where you just put pop-up ads and see who will respond. We’ve done some studies of some survey firms that are using a lot of river sampling, and one of these studies turned up that somewhere between 25 and 40 percent of the respondents were bots or survey farms. They get little compensation, so these people are doing—there’s an incentive to create a fictitious respondent to get the compensation.

And what’s really pernicious about these operations is that they understand that the survey is most likely to take a person whose demographics are hardest to sample, because those people don’t answer their phone very much. And who are those? Those are low-education minority males.

So the groups that are hardest to sample get overweighted when they do the sampling weights to make the survey representative. So those fictitious characters are really messing up many of the polls that people have. That said, most of the reputable organizations that are doing surveys, or media firms that are using surveys—like a Fox News poll or New York Times or the ABC–Washington Post—are all using that other methodology, which is more insulated from that.

The polling has gotten way better than it was a long time ago, like just steadily better. What’s changed is our expectations about what information we’re able to get and how detailed it will be. Twenty years ago, nobody expected any good polls at the state level, and now everybody expects really good polls at the state level.

There’s been a rise in expectations of what the polling industry can produce, as well as a degradation of phone polls. Nobody really does phone calls anymore. Pop-up ad polls are bad. If somebody came to me and said, “I’m not in a rush to do this study. What’s the best way to do it?” I’d say, “Use the US Postal Service—one of the oldest methods we have.”

Dench: I like the low tech. I think to close that conversation—there’s still great interest in the mechanisms of poll watching and a request for you to come up with some better way, since there’s not been improvement in this space, better ways of doing the mechanics of poll watching—all the approaches that you would recommend. What about private companies? I’m learning the concept of “civic tech.” I’m not sure I know what that is.

Ansolabehere: One of the great things about the world we live in right now is that the explosion of technologies—like things that we have, like cell phones and such—has completely changed our ability to see something and communicate it. So if you are a poll watcher—and you’re allowed to be a poll watcher—if you’re a poll watcher, you can actually alert somebody immediately if there’s a problem.

Twenty-five years ago, in the 2000 election, it was hard to alert people that there was something going on, and it was hard to know how to do that. But now you can take photos of it, send it, and put it out in social media. And those are all things that are actually really healthy.

And that’s what civic tech is a lot about: trying to capture that space. In every domain I’ve worked in and work in, the new technology has just been revolutionary in a good way. So, in redistricting in 2010, it was really expensive to get a software license to actually draw a map. By 2020, every person can do their own redistricting maps for free online.

There’s software like Dave’s Redistricting App that allows you just to go and play around—super easy to use, point and click. That has empowered all the civil rights groups to see what’s happening and to intervene and to lobby the state legislature, to get their representatives to say, “No, no, no, there’s another way to do this that’s better.” And so a lot of this technology that I’ve seen emerge in the democracy space has really revolutionized it in a good way.

Twenty-five years ago, in the 2000 election, it was hard to alert people that there was [a problem at a polling place], and it was hard to know how to do that. But now you can take photos of it and send it and put it out in social media. And those are all things that are actually really healthy.

—Stephen Ansolabehere

Dench: Last question. Looking ahead to 2028 and maybe staying away from the really obvious and unanswerable—do you have any tips? What should we be looking out for?

Ansolabehere: Both parties are going to have open primaries, and both parties have actually really good benches. It’s the first time in a long time that the Democrats have had a deep bench to draw from. So I think we’re going to have really excellent primary elections with some real choices on both sides.

I think the last real time we had an election like this might have been 2016 or 2008, and people are going to be really engaged, like, in both parties, which is going to be, I think, very good and healthy.

The general election will be, I think, one of the most fascinating things to watch. In 2028, it will be the true moment of a generational change. There will be no baby boomers on the ballot. I could imagine both parties not only going young but going very young. So we might see a really rapid generational change coming up.

Banner illustration by Brian Stauffer

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast