A Breakthrough for Studying Diseases of the Brain

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, is a neurodegenerative disease linked to repeated head injuries. It has been found in professional athletes, soldiers, and others who have experienced years of those traumas. New research from Harvard Griffin GSAS alumni Chanthia Ma and Guanlan Dong may help us better understand this condition. Their study looks at the smallest units of brain biology—individual neurons—and finds surprising clues written in the DNA itself. Using single-cell genome sequencing, they discovered that neurons in people with CTE carry distinctive patterns of genetic damage—patterns that may overlap with those seen in Alzheimer’s disease. In this episode of Colloquy, Ma discusses how her work not only sheds light on how brain trauma leads to long-term decline but also hints at possible shared mechanisms across different neurodegenerative conditions.

This transcript has been edited for clarity, correctness, and concision.

For those who may have heard of CTE from stories about football players or boxers, what exactly is chronic traumatic encephalopathy? And how does it differ from other brain diseases like Alzheimer’s?

Yeah. So CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, is a neurodegenerative disease that develops after years—oftentimes up to twenty years—of mild, repetitive head impact. The key difference between CTE and Alzheimer’s disease is that even though they are both diseases of what we call the tauopathies—so they are both diseases of tau protein—the key difference is what causes them. For CTE, we know the distinctive cause is these years of head impact. For Alzheimer’s, for most people, we don’t really know what is causing Alzheimer’s disease. For Alzheimer’s disease, in 1 percent of individuals, it is a familial gene. For the general population, there are risk factors that we’ve studied. But for CTE, we can say that it seems likely it develops in the brain after years of mild, repetitive head impact.

The symptoms of CTE include emotional difficulties, mood swings, short-term memory problems, issues with sleeping, headaches, and depression. And as you get to more advanced symptoms, you would have executive dysfunction, trouble speaking, and issues with daily activities, even culminating in self-harm thoughts or behaviors. And I think that is a lot of where we see CTE come into the news and the media—seeing individuals who have these later stages of CTE where they are having issues with aggression and self-harm. But the diagnosis for CTE can currently only be made neuropathologically.

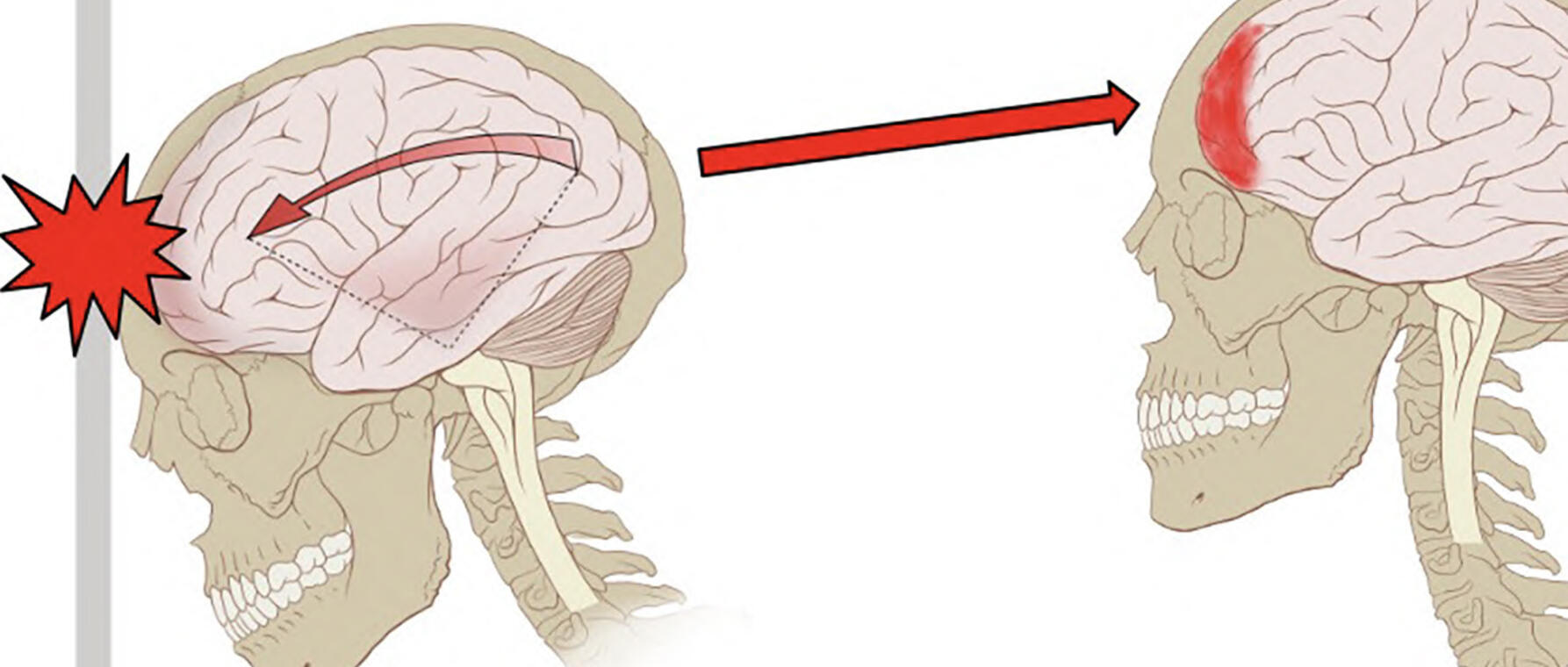

For the pathology—and this is why there is that original link to Alzheimer’s disease—it is because CTE is diagnosed by looking at the accumulation of tau protein in the brain. And we know that in Alzheimer’s disease, there is tau and beta amyloid as well. And for individuals with CTE, especially in the later stages, there is a huge accumulation of tau protein, especially in the sulci of the brain. And this is—for those not familiar with the anatomy of the brain—you have the gyrus, which is the surface of the brain, as well as the sulcus, which is where the brain tissue invaginates. In the early stages of CTE, tau is found in the sulcus only. In the later stages, you find tau as well as markers of neurodegeneration spread throughout the whole cortex. And that is how our collaborators at BU, Dr. McKee, who is the expert on CTE, have been diagnosing CTE.

Your study looks at DNA mutations inside neurons, which most people think of as nondividing, stable cells. What led you to suspect that tiny changes in neuronal DNA might help explain why some people develop CTE after repeated head injuries and others don’t?

Our lab, before I joined as an MD–PhD student, had already been looking at somatic mutations. And it is correct that you say these are single DNA changes inside individual cells. We looked at aging brains as well as diseases of DNA repair. And we found that in older brains as well as in these other diseases, there was an accumulation of somatic mutations. These are mutations post-conception—not mutations you would get from a parent—in these nondividing cells, which are the neurons of the brain. We found in our lab that as you age, there is an accumulation of somatic mutations in the brain in aging and in diseases of DNA repair. So this kind of links the idea of disease and lifespan and aging with the accumulation of somatic mutations.

So that is why we are interested in looking at cells that are nondividing, because even though they do not divide, they can still accumulate mutations in their DNA through different processes that we study in our papers and in other similar labs.

You used a method called single-cell whole genome sequencing in your research. Can you walk us through, for those of us who aren’t neuroscientists, in simple terms what that technique is, what it allows you to see, and why it is a breakthrough for studying diseases of the brain?

So we used single-cell—which means individual cells—and whole-genome sequencing—which means mapping out the DNA of the entire genome of that cell. And it is groundbreaking for studying diseases of the brain because neurons are nondividing cells. Most of the time, when we are thinking about studying DNA, we take a lot of cells mixed together, like when we take a blood sample or swab our cheeks. But when we sequence all those cells together, it is actually just an average. Previously, we did not have the technology or the power to sequence individual cells. We need a large amount of DNA to conduct sequencing. Now, with our novel techniques, we are able to sort individual neurons and amplify the DNA of those neurons to a level at which we are able to sequence the DNA. And we are also able to sequence the DNA at a depth high enough—which requires a lot of computational power—to get the whole DNA sequence of individual cells.

And that is a pretty new development: to be able to sequence at such a depth that we can map out exactly which mutations happen at a single-cell level. Previously, when you take cells from a different part of the body, like skin cells that divide rapidly or blood cells that divide rapidly, you gain a lot of information because those cells come from a progenitor cell. Sequencing a couple of thousand of those cells gives you similar information from that progenitor. But in neurons, because they are nondividing and you want the information from that individual cell, you need the technology to amplify it and to sequence it at a depth where you can confidently call mutations.

You’ve mentioned the different stages of the disease and that it is progressive. If it takes place in cells that are by definition nondividing, how does it spread?

I don’t think our findings give us a definitive answer for that because we were not looking at inflammatory cells of the brain, like microglia and other immune response modulators. But we think that by looking at the accumulation of somatic mutations, it means that something is going wrong in that part of the brain. Like I said, in earlier stages of CTE, the accumulation of abnormal proteins—tau—in the brain only happens in the sulcus. But we see that as the disease progresses to later stages, tau spreads across the rest of the brain, not just to where the originating force from head trauma occurs. Oh, and I forgot to mention earlier: the reason tau accumulates in the sulcus is because studies looking at the physics of head trauma show that the greatest force from repetitive head impact occurs in the sulcus. And that aligns with where the most damage is seen in the early stages.

We used single-cell . . . and whole-genome sequencing—which means mapping out the DNA of the entire genome of that cell. And it is groundbreaking for studying diseases of the brain . . .

You’ve discovered that people who experienced repetitive head impacts but did not develop CTE did not have those same DNA changes. What does that tell you about the factors—genetic, environmental, or otherwise—that might make some individuals more vulnerable?

I want to preface that our study is actually the first single-cell genomic investigation into CTE, given that it is a disease still being described and studied. What it looks like is that head trauma over many years of repetitive impact starts some sort of process that leads to the accumulation of tau we see in CTE. In some people, this process goes all the way to CTE and neurodegeneration, and in some, it does not. So the question is less whether there is something predisposing individuals to CTE, and rather that in individuals who do develop CTE, some neurodegenerative process occurred. The somatic mutations are telling us that this is a downstream effect of CTE, not a cause of it.

What I hear you saying is that because this is not something passed from generation to generation, it is not like you can do DNA screening for those who maybe should not be playing football or boxing because they would be predisposed to developing CTE?

Yeah, our study does not show—our evidence does not lead us toward there being some gene that predisposes you to CTE. Rather, we are hoping that our study reinforces that CTE is a real disease, it is linked with years of head trauma, and that these findings can hopefully influence athletes’ activity choices. Hopefully, they give us an idea of what switch happens when the brain goes from accumulating damage to developing neurodegeneration. Because if you actually look at the brains of individuals in stage 1 and stage 2, it is just tau in the sulcus. As you move to stage 3 and stage 4, these are holistic markers of neurodegeneration. It is brain atrophy. You see an increase in ventricle size, which is a sign of atrophy, and it is not just in one isolated area. So we think some sort of inflammatory process may kick-start the neurodegenerative process that then makes CTE a neurodegenerative disease, similar to Alzheimer’s.

Is there anything about this study that could eventually help doctors diagnose CTE in living patients? Does it still have to be done neuropathologically?

There have been imaging studies done in CTE. There are many imaging studies done in Alzheimer’s disease right now. There are PET scans, PET tracers for amyloid. There are some tau scans done for Alzheimer’s disease, but mostly in a research setting. I think similar studies could be done in CTE once we develop technologies where you can do somatic mutational testing—which currently requires a lot of computing power—to provide diagnostic information. But that would need to be considered alongside symptoms of the disease, given that CTE is confirmed neuropathologically and often diagnosed clinically through symptoms like mood changes, depression, and executive dysfunction.

We think some sort of inflammatory process may kick-start the neurodegenerative process that then makes CTE a neurodegenerative disease, similar to Alzheimer’s.

Sampling brain tissue is very difficult in living patients. But looking at ways of accessing tissue like blood, where we can learn more about the brain, you cannot find information about somatic mutations of neurons from blood, but maybe other inflammatory factors could help.

So, building on the work you have just done, what’s the next step for understanding the process of neurodegeneration that takes place with CTE?

For my study with CTE, we looked at single-cell genomic changes in the brain. Our lab is also looking at other ways of studying CTE as well as other neurodegenerative diseases. We have other studies in preprint now where we looked at signatures of oxidative stress and topoisomerase-related deletions. As we study that, we will have a better idea of why those factors are linked with neurodegeneration. Topoisomerase is related to RNA transcription—when DNA twists itself incorrectly. And earlier I discussed studies our lab has done on a disease of DNA repair. In these nondividing cells, it seems that the ability to accumulate DNA damage is what is causing these somatic mutations and leading to an elevated number of them. This seems to be linked with aging, lifespan, and neurodegeneration.

So some modulator of DNA repair mechanisms could potentially be translated into clinical care—something that could boost our response to oxidative stress, whether through medicine, lifestyle, or diet. The drugs that currently target topoisomerase have many side effects and are mostly used in cancer, so probably not good to test right now. But understanding that the way our body repairs DNA damage is intimately linked with aging and disease—specifically neurodegeneration—is important for future research.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast