A Passion for Policy

How Radhika Mathur’s time in the White House will inform her academic career

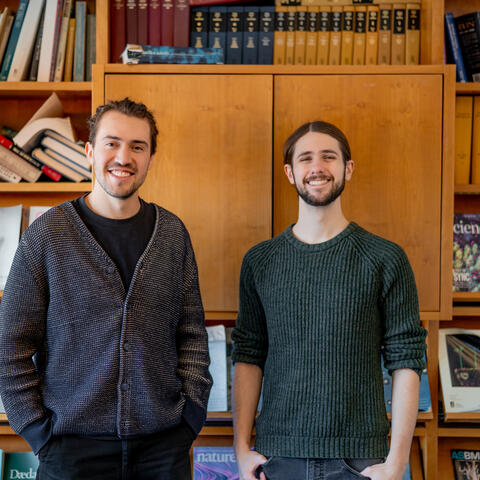

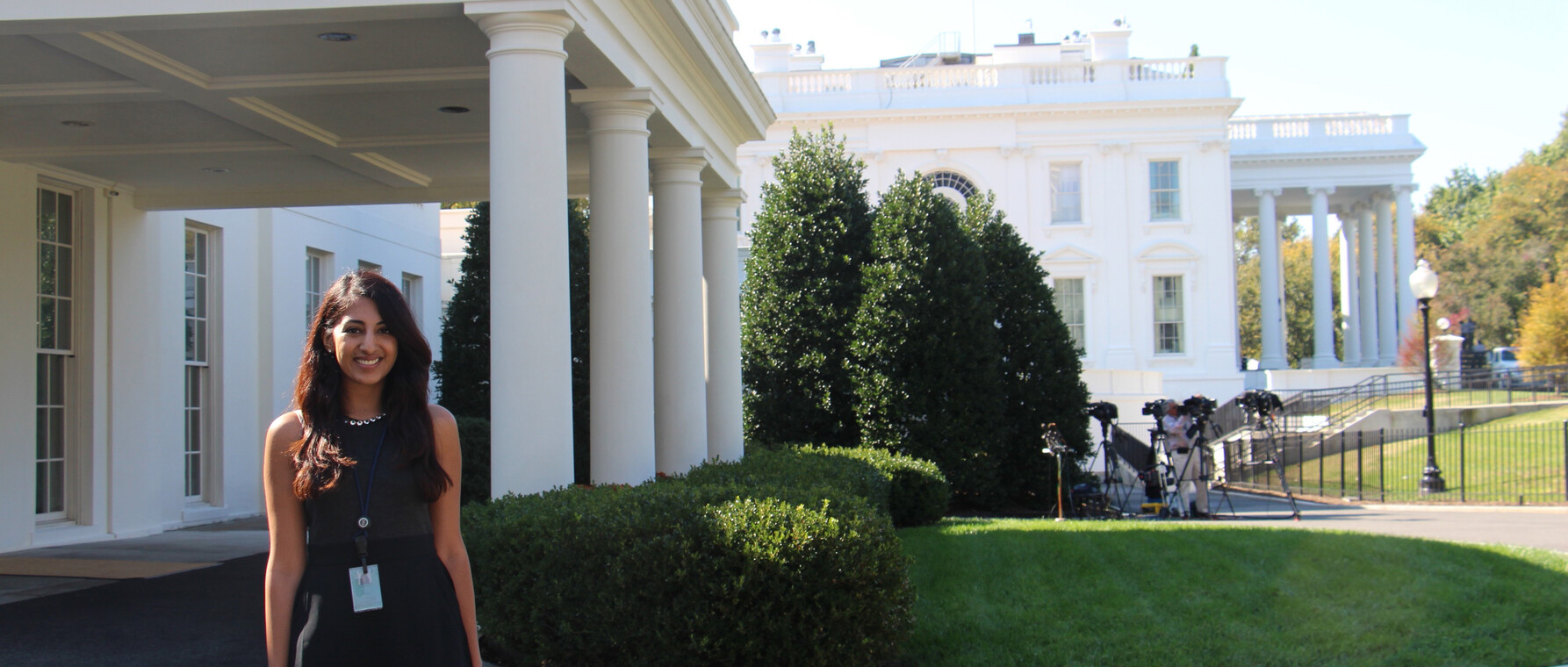

Every day between September and December 2016, Radhika Mathur, a PhD candidate in Biological and Biomedical Sciences (BBS), would stand outside the West Wing of the White House and take the same photo. “I wanted to soak everything in,” she explains. “I kept thinking ‘I cannot believe I’m here.’”

Here was the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), where Mathur wrote and edited policy reports, attended interagency meetings and helped put together transition memos for the new administration. “As the Science Division intern, I worked with basically everyone in the division, which allowed me to participate in many different projects at OSTP.”

While double majoring in economics and molecular & cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley, Mathur took two classes that set her on the path to both the lab of Dr. Charles Roberts (now at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee) and the White House. “I took a biology of human cancer course, and I quickly knew I could see myself investigating cancer biology during graduate school.” The second was a macroeconomics course taught by Dr. Christina Romer, the former chair of the Council of Economic Advisors in the Obama Administration. “That was the first moment where I thought ‘wow, I want to work for the president someday,’” Mathur remembers.

A Different Path

Mathur is a member of the Harvard Therapeutics Graduate Program, which aims to provide students with both academic and real-world experience in therapeutics discovery. Students are expected to complete a hands-on internship and most choose to spend those months in the pharmaceutical or biotech industry. Mathur, however, wanted something different. “I have always followed policy and politics closely,” Mathur explains. “Science policy felt like a great way to combine my interests in biomedical sciences and politics.”

I believe the biomedical sciences have an incentive problem—there’s the reproducibility crisis, postdocs are not paid enough—and I don’t think we are doing the best work we can to solve these problems.

Science policy is a broad field that includes everything from advocating for more cancer research funding to analyzing disaster preparedness. Luckily for Mathur, her main supervisor during her internship, Eleanor Celeste, has an extensive policy portfolio, allowing Mathur to dip her toes into a number of different projects in science policy. “Celeste was on the President’s Precision Medicine Initiatives team, and she also worked on biosafety and biosecurity policy as well as some projects related to forensic sciences,” Mathur lists off quickly. “One of the projects we worked on, for instance, was looking at how to modernize medico-legal death investigations, which determine the cause of suspicious or unexplained deaths and are currently not standardized across states.”

An unexpected benefit of Mathur’s time at OSTP was a change in what she saw as the path to professional success for women. “We’re told that to be successful in the sciences, we have to act like men: we can’t be ‘emotional’, we have to dress in a certain way,” Mathur says. But at OSTP, surrounded by women, Mathur saw that all of that advice was rubbish. “These women were passionate about their work, they wore whatever they wanted and they were incredibly successful.”

The Bigger Picture

In the lab, Mathur looks to the microscopic, rather than macroscopic, world, focusing on cancer biology. In the classic view of cancer, a small number of critical genes are mutated, causing abnormal cell proliferation that may lead to a tumor. But in the last few years, it has become clear that cancer is not just caused by changes in the DNA sequence, but also by three-dimensional changes in the structure of DNA. This new field of cancer epigenetics is focused on a number of complexes that control the architecture of our DNA.

One such example is the SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin-remodeling complex that is mutated in 20 percent of human cancers. SWI/SNF can remodel nucleosomes, a form of chromatin that our DNA takes when it is coiled around proteins called histones.

“We found that SWI/SNF regulates gene expression globally in the cell, through their critical role in control of enhancers, the regions of the DNA that increase the expression of genes,” explains Mathur. Which enhancers are on and off differs between different cell types. According to Mathur, SWI/SNF binds these enhancers differently in each cell type. Binding then mobilizes nucleosomes in that DNA region and this eventually leads to changes in gene expression levels.

But what happens when SWI/SNF itself is mutated? “When you lose SWI/SNF, you lose control of your enhancer activity. So many of the genes that are supposed to be on in a particular cell type, are off,” explains Mathur. Mutations in SWI/SNF lead to an extensive deregulation of gene expression, which inevitably affects tumor suppressor genes and results in cell proliferation.

Mathur acknowledges that the thought of thousands of one’s genes becoming deregulated is scarier to than a single gene mutating. “But,” she’s quick to point out, “we do have ideas of how to target these cancers and there are already two therapeutic approaches in development.”

Merging Policy and Science

“I think cancer epigenetics is one of the most exciting areas of research right now,” Mathur confesses, and she’s not done with it. Mathur plans on continuing in academia, but she also plans on staying aware of the structural problems in biomedical research. “I believe the biomedical sciences have an incentive problem— there’s the reproducibility crisis, postdocs are not paid enough—and I don’t think we are doing the best work we can to solve these problems.” These are issues science policy can and should address according to Mathur, and her experience at OSTP gave her a model for reconciling her love of cancer research with her passion for policy. “Many of the people I met during my internship don’t work in policy full time,” she explains. Science experts were brought to the table where policy decisions were made, and their presence had a real impact according to Mathur. “Speaking up about problems and discussing potential solutions is vital for scientific research, and I will continue doing so after I graduate.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast