Forgive Us Our Debts

How notions of sin shape the ways we think about money, forgiveness, and charity

Gary Anderson, PhD ’85, stumbled on the research that became the subject of his most well-known book, Sin: A History. Poring through the Dead Sea Scrolls and other primary sources on second temple Judaism, Anderson, the Hesburgh Professor of Catholic Thought at the University of Notre Dame, discovered that the conception of sin changed dramatically across the biblical era. He says that sin had developed very specific economic resonances by the time of the New Testament—resonances that continue to shape how we think about money, debt, forgiveness, and charity.

How is the idea of sin treated in the Bible?

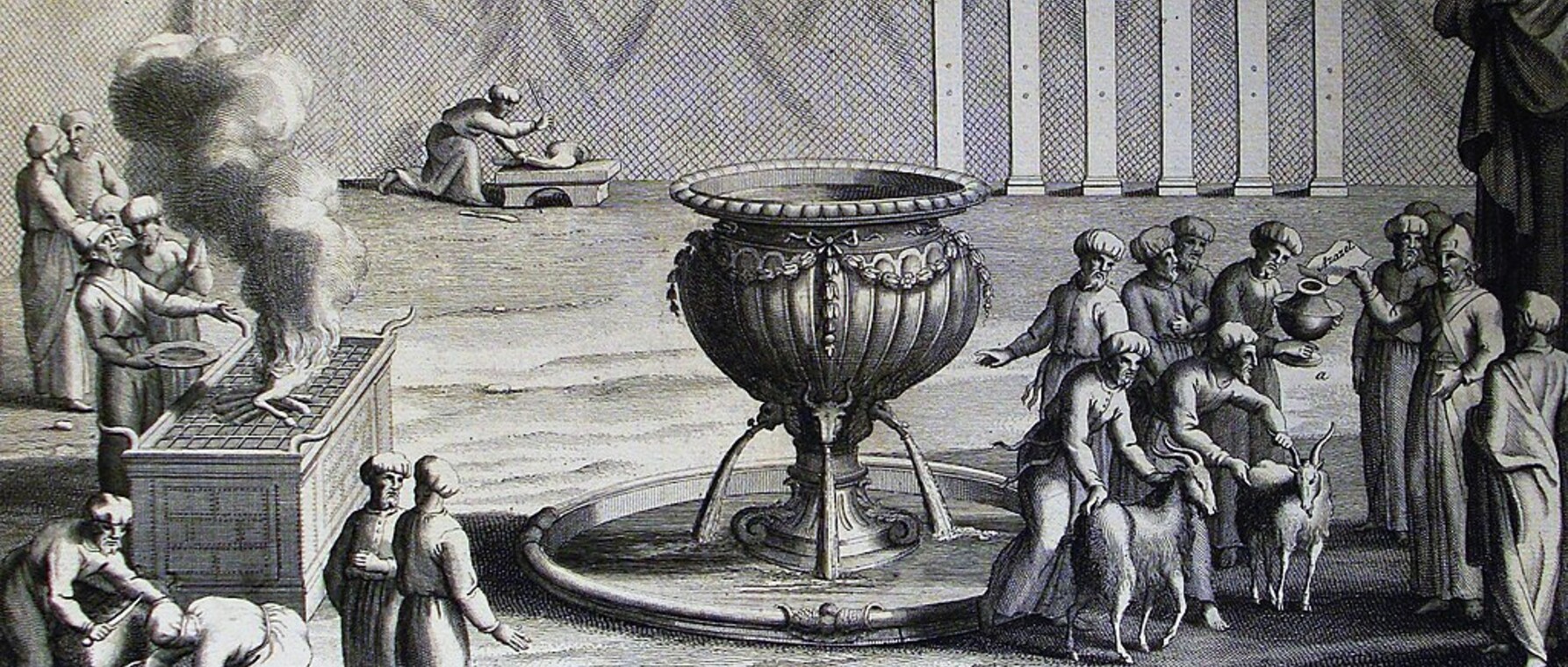

In the Hebrew Bible proper, although there are a large variety of metaphors for sin, the metaphor that takes pride of place and that is used by far the most is that of sin as a burden that individuals bear on their backs. Forgiveness of sin, then, means removing the burden from the back of the person so afflicted. So, it's not by accident in the Hebrew Bible that the principal ritual for eliminating sin is the scapegoat, an animal that carries the burdens—literally the weights of ancient Israel—into the wilderness.

When we move into the period of Second Temple Judaism—the period of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the rabbinic writings—that idiom gradually disappears from everyday speech. Of course, it’s in the Bible, so it's not lost forever, but it's no longer a productive idiom. The idiom that replaces it is sin as a debt. And so, stories told about sin and the forgiveness of sin in this period increasingly revolve around individuals who owe money and are relieved of what they owe.

Once we conceive of sin as a debt, this generates the notion that meritorious activity creates a corresponding credit.

—Gary Anderson, PhD ’85

Does the New Testament make a more explicit economic connection by introducing the notion of sin as something remitted?

Oh, yes. The reason why Jesus tells stories about debtors and creditors is not just because he's making it up. This is the language of his day, describing human sinfulness in terms of debts remitted either to God or to your fellow man. Everybody knew what that meant.

Colossians chapter 2 verse 14 fits hand and glove there: “having canceled the charge of our legal indebtedness, which stood against us and condemned us; he has taken it away, nailing it to the cross.” Why did this become one of the most cited New Testament texts by the early church theologians? Because they thought of sin as a debt. And here we have a text that says Jesus takes this bond of indebtedness and rips it in two on the cross. He nullifies it.

Once we conceive of sin as a debt, this generates the notion that meritorious activity creates a corresponding credit. These credits, in turn, were thought to collect in a heavenly treasury and could be used to pay down the debt of one’s sins. This concept defined the way both synagogue and church would understand sin and forgiveness. The Lord’s Prayer is perhaps the best barometer: “Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors.”

Wasn’t that transactional, economic notion of sin and forgiveness what Martin Luther was so worked up about?

The notion that good deeds were recorded in a treasury in heaven became a point of major disagreement during the Protestant Reformation. The Catholic tradition of a treasury of merits was tied to the theology of indulgences that was rejected root and branch by Protestant reformers. They had great difficulty with biblical texts—both in the later texts of the Hebrew Bible and in the New Testament— that addressed this treasury in heaven. So, you have Protestant thinkers working over time to deny what seems to be the simple sense of these texts because of its association with what they think is a terrible Catholic heresy. Of course, Catholics viewed the treasury of merits as deeply grounded in scripture and often compared this notion to the Jewish concept of the “merits of the fathers.”

Debt—particularly the national debt—has been much in the news in recent months. How does this metaphor for sin continue to resonate today?

The issuance of a note of debt is grounded in trust and belief. Indeed, the term creditor comes from a Latin root meaning “to believe.” We don’t usually reflect on the importance of this sort of faith for the flourishing of our economy, but when a financial crisis hits, all of a sudden it confronts us head-on: Will credit markets continue to operate? Will my money retain its value over time?

The Jewish and Christian traditions utilized this sort of economic anxiety to draw a compelling picture of another sort of “economic” market. The most secure investment one could make, they argued, was to donate one’s money to the poor. Because God was the guarantor of such financial risks, one could be assured that radical generosity would be rewarded. Pope Leo the Great went so far as to say that refusing to give—to become a creditor—to the poor implied a lack of belief in God.

So, while I don’t have any specific wisdom on the wrangling over the country’s national debt, I think it’s important to understand that these problems are grounded in trust and belief, which has been a challenge for humanity since the beginning of time.

Curriculum Vitae

University of Notre Dame

Hesburgh Professor of Catholic Thought,

2003–Present

Harvard Divinity School

Professor of Old Testament/Hebrew Bible,

1995–2003

University of Virginia

Assistant/Associate Professor of Hebrew Bible,

1985–1994

Harvard University

PhD in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, 1985

Duke Divinity School

MDiv, 1981

Albion College

BA, 1977

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast