Beyond ‘Authenticity’

Enabling Black men to embrace their own multifaceted humanity

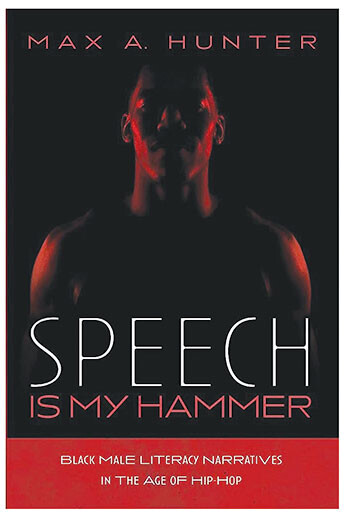

Max Hunter, AM ’06, is a leader in the Community Innovation Hub at Seattle Children’s Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic. In his 2022 book, Speech Is My Hammer, Hunter explores the literacy stories of Black male artists and thinkers—from Langston Hughes and Richard Wright to Malcolm X and Stringer Bell, a fictional character from HBO’s award-winning series, The Wire. He also writes candidly about his own experience growing up poor, Black, and intellectually curious in the housing projects of San Diego. The goal of these meditations, he says, is to help free Black men from the performance of authenticity so that they can embrace their own multifaceted, transcendent humanity.

What was your own literacy journey as a Black male?

I grew up mostly with my mother in the projects of San Diego, then went to a Catholic school in a white upper-class neighborhood in Southern California. I had some great teachers, but they were mostly white males. Those were my models for people who were highly literate.

At the same time, I lived in a region where gang culture was ascending and hypermasculinity was becoming more and more prominent. To perform my identity differently was to risk being perceived as soft or queer. The University of Waterloo Professor Vershawn Ashanti Young talks about this dynamic in his 2004 book, Your Average [N-word]. He begins recounting his experience with being afraid to bring a book into a Black barbershop because people might perceive not that he's less Black, but that he's queer.

The result for me was a lot of ambivalence. I was the kind of kid who would go to the library and check out all these books. When I was 17, one of my first big purchases was a set of the works of Sigmund Freud. I brought it home, set up in my bedroom, and immediately started reading through it, really struck by how self-aware his writing was. I got the idea, though, that if I pursued literacy as it was presented to me in academic settings, then I was somehow acquiescing to power—I was conceding that European culture was the pinnacle of civilization and abdicating my humanity and my masculinity.

You actually start your book with quotes from Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents, as well as Ellison’s Invisible Man, and Homi Bhabha’s “Of Mimicry and Man.” Connect the dots between the three thinkers and how they speak to the themes of Speech is My Hammer.

The thread for me is this ambivalence related to modernity. I gravitated to Freud’s notion—that we have the benefits of civilization, but at the same time society imposes these cultural ideals that make us unhappy—because it describes the kind of ambivalence I experienced in my own literacy journey and that I found in the narratives of other Black males.

At the same time, I was trying to identify examples of this ambivalence in Black male literacy narratives themselves. And lo and behold, there it was in Invisible Man, where Ellison writes of “a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids” who “might even be said to possess a mind,” but is invisible on a societal level.

I included Homi Bhabha’s quote from his essay “Of Mimicry and Man” for a post-colonial perspective. He writes that “the discourse of mimicry is constructed around ambivalence” because “it never wants colonial subjects to be exact replicas of the colonizers—this would be too threatening.”

The Duke University scholar Mark Anthony Neal talks about “illegible masculinities.” My book is in part about what we do to become “legible” and how Black males make choices regarding that legibility—just like Freud’s modern man, like Ellison’s invisible man, like Bhabha’s post-colonial mimicry. Black men are double-minded about the choices we make around literacy because they have consequences, both positive and negative.

How is the Black male experience of literacy shaped both by the desire for authenticity and resistance to socialization in mainstream culture?

Coming out of the Enlightenment, you had to be a certain kind of white male to be a citizen/subject. Reading that, African Americans—those striving to have their personhood and their citizenship recognized—tried to assimilate. They thought once they demonstrated they were capable of living a morally-disciplined life and adhered to a kind of respectability politics—including a certain kind of academic pedigree—they would be treated as equals. During the modern era, Black writers like Langston Hughes rejected the requirement to portray Black life in a way that mirrored and imitated whites. Hughes wanted to write about Black life as it was, which included writing about people who didn’t adhere to heterosexual gender norms— radical for the 1920s. He wanted the right to perform his identity on his own terms—to write about people who spoke in the Black vernacular—without being excluded.

There’s a tension there that Black folks still struggle with in our culture: socialization versus authenticity. Who's Black and who's not? I’ve experienced it myself. There was an incident with my daughter one time during a youth soccer game. Someone was pulling her hair. That made me angry. When I reacted, one of the Black men who was there kept calling me “Dr. Hunter.” He was reminding me that, because of my education and status, I probably shouldn't be using the language that I was using. In fact, I shouldn’t demonstrate affect at all. That’s the tension and the ambivalence—giving up a part of your humanity to conform to the sort of cultural ideals that Freud talked about in Civilization and Its Discontents.

Finally, you write that the goal of your book is “to encourage other Black men to examine and embrace their emotional and cognitive vacillation regarding their literacy performances.” Where do you hope the type of examination you propose would lead?

One of the things I hope it will do is to provide rest. I want Black people to be free from constantly living in a space of vigilance, knowing that their identity and gender are being policed. I want people to embrace the reality that human beings are multifaceted creatures. And I’d like to help people move towards the kind of human dignity that my grandmother was very committed to—acknowledging and accepting your humanity beyond the performance of your literacy or how people assess it. I see it again and again in Black male narratives—whether veiled as in Langston Hughes’ autobiography, The Big Sea, or unveiled in other places. This transcendent self-awareness is a prophylactic, so to speak, from the psychological harms of our racial caste system.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast