Finding Secrets in Fossils

Sarah Losso, PhD ’24

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

Sarah Losso is a 2024 PhD graduate in the Department of Biology, where she investigates trilobites, a group of ancient arthropods. Losso discusses the findings of some of her work, how her fascination with rocks led her to Harvard, and the traveling opportunities she has had while at Harvard Griffin GSAS.

Tracing Evolution through Trilobites

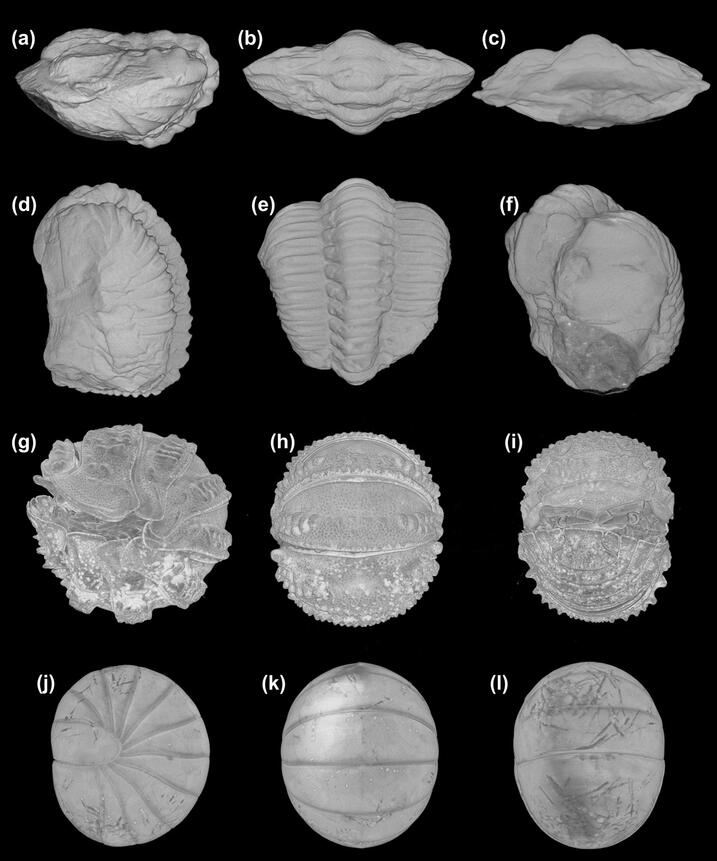

Insects, crabs, lobsters, and scorpions are all part of the most diverse group of animals—arthropods. Arthropods live in oceans, in the air, and on land. I’m interested in understanding how the first arthropods evolved. To do that, I study early arthropods like trilobites that are 500 million years old.

Naturally, a lot of my work involves the fossil record. It’s an incomplete source of information. To become a fossil, an animal had to die in the right environment, be lucky enough to actually fossilize and not be scavenged, and usually have a body with bones or shells (soft tissue tends to decompose more easily). Then it has to be found by people. So a lot of the fossil record is incomplete skeletons, pieces of bone, individual teeth, and things like that. Trilobites had a hard exoskeleton made of calcite that allowed some parts of them to fossilize easily, although their legs and gills were not as hardy. In some cases, the softer legs, gills, and guts also get preserved, but only under special conditions.

I have been researching a defense mechanism used against predation seen in trilobites and other living arthropods. Essentially, trilobites will completely roll up their bodies for protection if they feel threatened. We also see this in insects, isopods, millipedes, and armadillos. It prevents them from being eaten.

What’s interesting is that all of these groups have the same mechanism of protection despite not being closely related. They independently evolved this mechanism. Also, there are morphological constraints that the animals have to get around to roll their bodies up. It’s like they have a line of hard plates on their stomachs, and they have to figure out how to roll themselves up without breaking or bending the plates. Yet all of these animals figured it out, and they all do it the same way. Studying trilobites gives us insight into how these different animals developed this mechanism.

Combining Biology and Geology

I’ve always liked animals and rocks. Growing up, my pockets were always full of sand, because I would go to the beach and pick up rocks. When I went to college, I studied biology, and I was also really interested in environmental science and geology. One of the classes I took was on the history of the Earth. It was fascinating to understand how old our planet is and all the processes that made it the way it is now.

In my senior year in college, I had a bit of a crisis because I didn’t know how to combine my biology and geology interests into further research. My professor said, “Well, that’s basically what paleontology is.” I did a master’s degree studying trilobites, and while I was doing that research, I went to a conference to present my work. I happened to meet Professor Javier Ortega-Hernández, who was just about to start a lab at Harvard, and we had a great conversation. I applied to Harvard and now I’m his first student here.

Fossils and Fieldwork

At Harvard Griffin GSAS, I’ve had opportunities to travel and go to a lot of cool places. As a researcher, I have been all over the world—Estonia, Spain, England, and Ireland as well as in the US in California, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—to present my work. It’s amazing to go to a new place and talk about science with other people and get the chance to start new projects together. You get people in one room to share these fascinating ideas.

Another part of my job as a paleontologist is fieldwork. We go and try to find new fossils. For that work, I have gone to places as close as Upstate New York and as far away as Morocco. In your downtime, you get the chance to explore and chat with the researchers on your team, and while you’re working, you start finding things that no one has seen for hundreds of millions of years. That’s just out of this world.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast