Deciphering Biology’s Big Data

Nicol uses statistics to enable the development of revolutionary new disease treatments

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

The first sequence of the DNA comprising the human genome, famously undertaken in 1990 by the Human Genome Project, took thirteen years to complete. Today, a human genome can be sequenced within a day, thanks to next-generation sequencing technologies developed over the past 20 years. The power and speed of these methods also allow researchers to gain specific insights that were impossible with older techniques—for instance, detecting genetic differences between cells within an individual. Next-generation sequencing technologies are also used to track the details of how single cells express their various genes.

The accessibility of such a large amount of specific information, however, also poses challenges to scientists regarding how to read, interpret, and analyze the massive amounts of data they can now obtain. “You can look at individual cells in a tissue and measure the expression of every single gene within that particular cell,” explains biostatistician Phillip Nicol, “and you end up with giant datasets that are statistically nonstandard––they require new statistical methods in order for you to gain biological insight.”

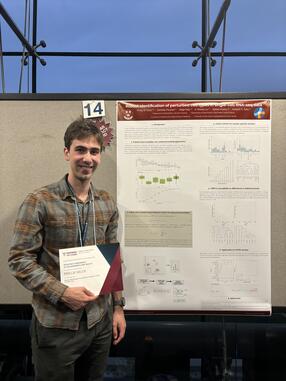

As a PhD candidate in biostatistics at Harvard’s Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) and T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Nicol develops tools that can help scientists answer those questions. Collaborating with biomedical researchers, Nicol makes it possible to detect trends, visualize data, and verify the accuracy and significance of experimental results that could lead to revolutionary therapies for the treatment of cancer and other diseases.

Billions of Cells, Thousands of Measurements Each

In his research, Nicol has focused on the data from single-cell sequencing techniques, which provide genetic sequences from individual cells within a tissue sample, allowing for the study of differences among cells and their behavior. “The data is quite messy and very large, because you have billions of cells in a particular tissue sample, and you’re making thousands and thousands of measurements for each particular cell,” Nicol explains.

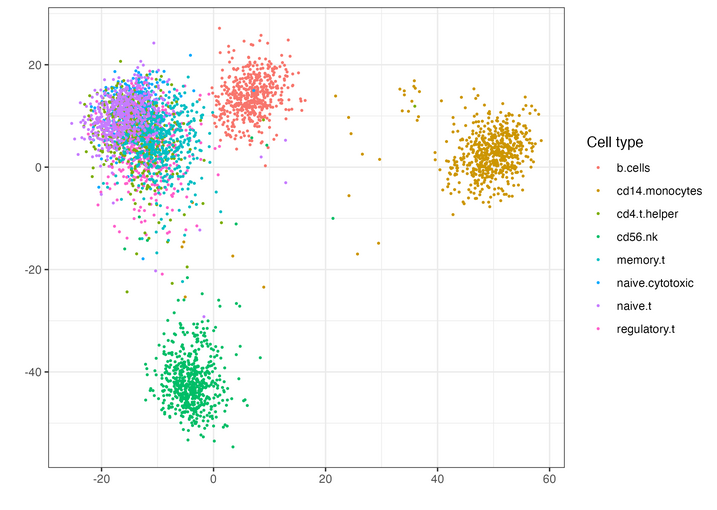

Within the domain of single-cell sequencing data, Nicol specializes in working with the results of RNA sequencing methods that can reveal which genes a cell is expressing and, by extension, how that cell behaves or responds to its environment or other cells. While DNA stores all of the genes that a cell might use, only some of those genes are actually expressed through a process called transcription, which produces a messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule whose genetic code corresponds to the information encoded in the gene to be expressed. This information, in turn, dictates a sequence of amino acids to produce protein in the cell via a process called translation. “Looking at the mRNA transcripts, you can see what genes those transcripts came from,” says Nicol. “The genes are what get transcribed to eventually make proteins, and then the proteins do things. So the idea is, by measuring the expression of genes in these cells, you can get an idea of each cell’s function. And this is important when you’re studying a disease.”

RNA sequencing technologies are relatively new, and there are still challenges and unsolved problems in how to analyze the datasets they generate about how the body responds to certain diseases, medical treatments, or environmental stressors. Nicol develops statistical analysis software, balancing the need for theoretical rigor, computational efficiency, and an accessible design so that other researchers can conduct the analysis themselves.

“Because the data is so large, the software’s code needs to run very efficiently,” he explains. “And because I want to help biologists answer their questions, I want to make my software user-friendly. When we finish our project, we then release the software to everybody in the world. If others have a similar question, then they can try to use it to get an answer.”

[Nicol] discovered a completely novel algorithm . . . that enables scalable estimation for datasets with millions of cells.

–Professor Jeffrey Miller

By responding to the needs of his bioscience collaborators, Nicol also aims to address broader shortfalls of existing methods in genomic data analysis by offering powerful new alternatives. As Jeffrey Miller, an associate professor of biostatistics at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health and one of Nicol’s co-advisors, explains, “the leading existing methods often introduce technical artifacts that can produce spurious findings or are not computationally scalable to large modern data sets.” Miller points to a recent paper in which Nicol demonstrated that a type of statistical method called a generalized bilinear model can lead to more accurate findings in large genomic datasets when applied to single-cell studies of gene expression. “Furthermore, he discovered a completely novel algorithm––iteratively reweighted singular value decomposition––that enables scalable estimation for datasets with millions of cells.” Or, in other words, a new computational procedure that performs efficiently and produces accurate results, even with the massive and multi-dimensional datasets generated in single-cell sequencing studies.

Paving the Way for New Discoveries

Nicol’s research in biostatistics depends on collaborations with other researchers that inspire applications for his biostatistical methodologies. One is in the development of cancer immunotherapy, a relatively recent branch of treatment that aims to use the body’s own immune system to fight against tumor cells.

“One of the big questions in this area is, ‘What is it that makes some people respond well to this treatment, and what is it that makes some not respond to the treatment?’” Nicol says. “I worked on a project looking at single-cell RNA sequencing data to see if there were any significant differences in particular cell types between responders and non-responders. I developed a method that allows you to compare two groups of cells and see differences between them. This approach could be applied to cancer immunotherapy and other conditions with both a control and a treatment group for comparison.”

Nicol is enthusiastic about both practical and abstract ways of thinking. As an undergraduate at Harvard College, he originally intended to focus on theoretical mathematics but then discovered the field of biostatistics at an Ohio State University lab during a summer undergraduate research program.

“I fell in love with biostatistics that summer,” Nicol recalls, “because it’s a mix of many things. I can use some of the theory I learned in math. I’ve always loved to code, and the computer coding aspect is huge in bioinformatics. And then developing something that solves a real problem that people care about was rewarding.”

At Harvard, Nicol works in a lab united by a general interest in statistical methods for analyzing data produced by genomic technologies, giving him plenty of opportunities to engage with new biomedical questions, data structures, and technologies. “I don’t work with a particular disease or animal, and I don’t have loyalty to a particular method,” he notes. “But whatever is at the cutting edge of genomic technology, that’s what I’m going to be thinking about.”

I don’t work with a particular disease or animal, and I don’t have loyalty to a particular method. But whatever is at the cutting edge of genomic technology, that’s what I’m going to be thinking about.

–Phillip Nicol

Rafael Irizarry, a professor of biostatistics at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health and also one of Nicol’s co-advisors, says the student’s latest project focuses on working with data from emerging technologies that detect variations in genes’ expression across spatial locations––a challenge that interests thousands of biologists worldwide.

“Despite widespread interest, there is currently no consensus on the optimal approach to addressing this complex problem, which involves analyzing tens of thousands of genes across tens of thousands of cells,” Irizarry explains. “Phillip’s creativity and profound understanding of statistics have enabled him to invent a method that is both accurate and efficient. The computational tool based on his groundbreaking idea is expected to gain widespread adoption in the scientific community, paving the way for new discoveries.”

Nicol plans to continue in an academic research career, and he pictures himself one day engaging with biomedical research technologies beyond what we can even imagine now. “It’s exciting to think about the far future,” he says. “Biologists will come up with even more interesting things that they can measure––and then, the same fundamental statistical principles could be applied in new ways to all these fancy new technologies. It will be important to continue to be a good statistician and follow certain principles, even when you’re dealing with new and exciting types of data sets.”

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health Cancer Institute.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast