Paying Attention

You might think you're focused and observant, until Christopher Chabris points out the invisible gorilla in the room.

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

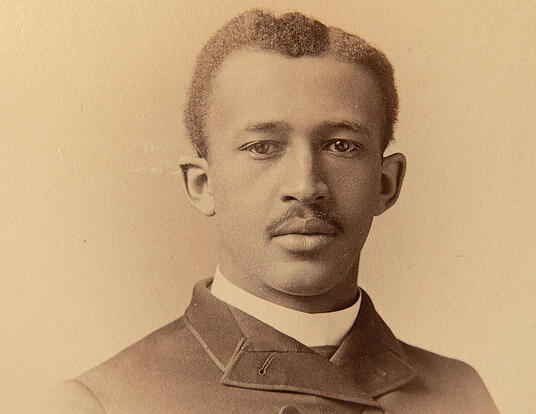

Work that Christopher Chabris, PhD '99, conducted on inattentional blindness won an Ig Nobel Prize, which honors "achievements that first make people laugh, and then make them think," and cautions us about the impact of increasing technological distractions on our interconnected world.

You studied computer science as a Harvard undergraduate, earned a PhD in psychology, and worked as a radiology research fellow before publishing papers in economics journals—plus you are a chess master. How do these seemingly disparate activities connect with what you do now?

I think they all are related, but by a series of adjacencies rather than a consistent, unified focus. I learned to play chess when I was five and later developed an interest in computer chess that naturally led to an interest in artificial intelligence. From there, I became curious about human cognition, neural networks, how the brain works, and, most broadly, in the causes and the consequences of the way we think and make decisions.

When I decided to concentrate in computer science, the program required that you take courses in a “breadth area,” one of which was psychology. That made sense to me because of my interest in artificial intelligence. Plus, I had tried physics and failed the introductory course!

So graduate study in psychology was a natural next step?

Yes and no. One of my undergraduate professors—and favorite people ever—was Stephen Kosslyn [John Lindsley Professor of Psychology in Memory of William James, Emeritus] and he offered me a job in his lab after I graduated. I knew I didn’t want to continue on with school, so I said “Great, sign me up.” Steve eventually talked me into pursuing an advanced degree.

While you were a graduate student, you collaborated with Daniel Simons on a project about inattention, known as the invisible gorilla experiment. What is the invisible gorilla?

The invisible gorilla is a cheeky name that Dan Simons and I gave to a book we wrote. It really refers to an experiment we did with students in a Harvard course we taught, inspired by the work of Ulric Neisser at Cornell in the 1970s. Research subjects were asked to watch a video of our students passing a basketball and count the number of times the ball is passed. During the video, a gorilla walks through the action and is visible for nine seconds, but many don’t notice it—as though the gorilla is invisible to them. It’s not really invisible—it just seems that way because people often don’t see it.

I was surprised at the results because the leading idea of how attention worked at the time was the “spotlight model”— that attention amplifies perception of everything within a certain limited zone of space. But the gorilla passes right through the zone of attention, and still isn’t noticed. The results added to the evidence for a competing explanation—that attention focuses on individual objects and switches between them. If it moves from object to object, and never happens to alight on the gorilla for some reason, then it’s as though you never saw it.

But about half of people do see the gorilla, yes? Why do you think that is?

I suspect that some trait must be involved, that some people are inherently more likely than others to see unexpected events like the gorilla. Dan and I and others have conducted studies since then with other types of events, but we haven’t found that trait yet, in part because it’s hard to trick research subjects repeatedly with unexpected events—once they notice one, they are on alert for more.

I’m convinced, though, that nobody is immune to this kind of inattentional blindness. Many drivers are certain that they can talk on their cellphone and observe what’s going on around them because they haven’t gotten into an accident yet—but that could simply mean they’ve been lucky or mostly drive on empty roads. They aren’t immune to inattentional blindness.

But aren’t you immune when you use a hands-free device?

The hands-free thing is an illusion because the problem isn’t taking your hands off the wheel. Everyone knows you can drive with one hand on the wheel. The problem is that carrying on a conversation with someone far away uses cognitive resources that divert attention from the process of driving. Even a clear cellphone connection is not as good as talking face-to-face; it saps more attention to decode the words and understand what’s being said.

What’s next for you?

I want to continue researching attention and inattentional blindness, which are increasingly critical issues as we develop more ways to distract ourselves. I’m also studying collective intelligence, figuring out how you can measure the intelligence of a team of people and determining how to increase the group’s intelligence. I find it interesting to think about the group as an organism with characteristic behaviors that can be measured and perhaps become more effective. It’s growing in importance because across a lot of fields, especially within academia, more work is being accomplished by groups. And maybe I’ll play some more chess.

CV

Geisinger Health System

Professor

Union College

Associate Professor of Psychology

The Invisible Gorilla

Co-author with Daniel Simons

Harvard University

PhD in Psychology, 1999

AB, Computer Science, 1988

Illustration by Tes One

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast