Colloquy Podcast: Whose Father Abraham?

What the Biblical Patriarch Means to Muslims, Christians, and Jews

We're in the midst of the Muslim holy days of Ramadan, just past Western Christians' celebration of Easter, and looking forward to the Jewish Passover holidays in late April. We often refer to these traditions as the Abrahamic faiths—a reference to the childless man chosen by God in the Jewish Bible to be the father of a great nation, and who's an important figure in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Today, many who work for religious understanding use Abraham as a point of commonality between those in the three different religious traditions.

Not so fast, says the Harvard Divinity School Jewish studies scholar Jon Levenson, PhD ’75. He says that, a bit like the old joke about the United States, Great Britain, and the English language, Abraham is the common figure that separates Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. "It is surely the case that Jews, Christians, and Muslims have more in common than their adherents believe," he writes in his 2012 book, Inheriting Abraham, "but the patriarch is less useful to the end of inter-religious concord than many think."

So how does Abraham and his story play out differently in the three traditions? Why is it important to understand those differences? And if Abraham is not the fulcrum on which efforts for religious conciliation can revolve, what are the areas of commonality that can foster peaceful coexistence, particularly today when it's needed most?

So we have Abram, who becomes Abraham, Sarai who becomes Sarah. Then we have Hagar, Ishmael, Isaac, and Rebecca. God makes promises and doesn't entirely deliver, but then he does, sort of, except then he asks Abraham to sacrifice the son he promised him, only to say, never mind. Can you synopsize and clarify the story of Abraham that I've just butchered?

Well, thank you. I don't think you butchered it all that much. Of course, it's hard to summarize such a deceptively simple text, which is full of intertextual connections, echoes, and foreshadowings of later texts and has such a rich exegetical history in the whole history of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam alike.

But I would say the key point in this narrative is promise, especially this notion of the promise of progeny to a man who's not only childless, but he has a barren wife—apparently infertile all her life. And now, according to some of the texts, more than infertile. She, in fact, is post-menopausal and highly unlikely to conceive. And I think that highly unlikely promise underscores the unique nature of this new group—of this group called the people of Israel, which is not listed among the 70 nations of the world that descend from Noah in Genesis 10.

It's a new beginning on God's part. It's not one of these, so to speak, primordial postdiluvian nations. It begins in response to God's calling Abraham and making what, on naturalistic grounds, seems to be a totally absurd promise. The truth is that in the Jewish framework, you really can't talk very long about God—that is to say, the God of Israel—without also talking about the people of Israel.

And Abraham is seen as the first father of the people of Israel. To be sure, the people of Israel have a prior father in Adam and in Noah and, therefore, are part of universal humanity. But at the same time, there's something special. They're singled out from the other nations by this promise.

And something similar can be said in the Christian framework about how long you could talk about Christ without also talking about the church. In both cases, there is a universal affirmation, but a singling out of a special person. And what this story tells is the many, many frustrations and detours that take place until the promised son, Isaac, is, in fact, born—all the false starts, the people you thought were going to be the heirs to Abraham and aren't.

And then, of course, there's the great text of Genesis 22, about which I wrote my third chapter in Inheriting Abraham, which is where Abraham is ordered to sacrifice Isaac, to give up Isaac. Isaac is, in turn, the father of Jacob, also known as Israel, and that's really where the people of Israel come into existence.

So it's a kind of history in narrative, semi-folkloristic or not so semi-folkloristic terms of the origins of this special, small nation that doesn't really seem to fit with the other nations and, at least in the minds of the authors, depends on a divine promise and on the fidelity of God to the promise—and maybe, to some extent, also on the fidelity of the recipient of the promise, Abraham himself, to that God. That, in very, very short order, and much too simplistically, is what the story is about.

How is Abraham used by those who want to ameliorate inter-religious discord? And broadly speaking, why do you think that the narrative might not necessarily be as useful toward that end as many hope?

Abraham is a central figure in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions. In the case of Islam, it tends to speak of itself in the Quran already as the religion of Abraham—in other words, a restoration of the religion of Abraham through the revelation of the Quran to Muhammad. Of the three, I would say that the figure of Abraham, broadly speaking, is most stressed in Islam.

The problem, though, is that the issue in the Abraham story is not just about Abraham. It's about what son will inherit Abraham, and by what means does one come to inherit the promise of Abraham? That's why I call the book Inheriting Abraham.

And I think if I had to choose a new subtitle instead of “The Legacy of the Patriarch in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam,” I would probably call it “The Disputed Legacy of the Patriarch in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.” Because the key thing is not just Abraham, but the multitude of sons—he ultimately ends up with eight sons. Who inherits him? And who inherits the promise? Who inherits the covenant, including the land promise that goes with the covenant?

And there is a Jewish studies scholar named Martin Jaffee who has a wonderful statement about monotheism in the so-called Abrahamic religions—monotheism, meaning the belief in just one God. Well, there's such a thing as a pagan monotheism. Ancient philosophers could speak of God in the singular theos, Deus—God in the singular. Especially stoics could talk about that—a pagan monotheism.

How is this Abrahamic monotheism different? Jaffee writes this. He calls it elective monotheism. It's not just monotheism. It's monotheism with a divine choice, i.e., an act of election on God's part to form a particular community. That's something these pagan philosophers did not have.

He talks about the essential marker of elected monotheism. He says it's “not the uniqueness of God alone or the oneness of God alone.” He says, “Rather, it lies in the desire of the unique God to summon from out of the human mass a unique community, established in his name, and the desire of that community to serve God in love and obedience by responding to his call." So there is a call of Abraham, but it's also a call of a particular community.

But these three religions, for reasons I've already described, don't agree on what that community is. Is it Israel? Is it the Jewish people? Is it the Church of Jesus Christ? Is it the Muslim ummah, the Brotherhood, or whatever one wants to call it, of all Muslims worldwide?

Which community is it? Which scripture is it that records and correctly interprets that call? Is it the Hebrew Bible and the Oral Torah by which Jews have interpreted this for about 2,000 or more years? Is it the Hebrew Bible, exegeted and extended and interpreted by the New Testament? Or is it the Quran, for which Genesis, the Old Testament, and the New Testament are not canonical scripture in spite of some overlaps and influences?

So in my opinion, it's a mistake to think we can peel away these post-biblical traditions—the Oral Torah, the Torah, the teachings of Talmud and Midrash for the Jews; the New Testament and church tradition for the Christians; or, for that matter, the Quran, the only scripture they have for Muslims. And say, let's get back to the Abraham of Genesis. Well, the Abraham of Genesis is interpreted differently by Jews and Christians.

And Genesis itself is not canonical scripture for Islam. So this puts a damper on claims, “Oh, we're all talking about the same person. We all have the same common founder.” My answer is yes and no.

To some degree, there are commonalities. They need to be mentioned more. They need to be stressed more by peacemakers, there's no question about that. But there are also enduring differences. And I have to say one other thing.

Abraham, the Abrahamic people, whoever they are—even if all three of these groups are Abrahamic—that's not all of humanity. If you say, let's make peace by going to Abraham—well, you just left off a lot of Hindus, Buddhists, Confucianists, secularists, Marxists. You left off an awful lot of people when you take the subsection of humanity represented by these three so-called Abrahamic religions. You may not be making peace as thoroughly as you think you are because there is an element of election even in the call of Abraham himself.

Let's talk a bit more about Abraham's place in Judaism. Are we justified in calling him the founder of monotheism?

The belief that there's just one God is never actually affirmed in Genesis about Abraham. He does build altars to the God who has revealed himself to him—various foundation stories for altars at which to sacrifice. You don't see him participating in the sacrifice of the people with whom he comes in contact. But the number of deities is not an issue in Genesis itself.

But in Second Temple and rabbinic tradition—Jewish tradition in, I don't know, third, second, first century BCE, first century CE, and then continuing in rabbinic tradition, Talmud and Midrash, really until current era—but certainly, that's the first five or six centuries of the Common Era—there's a strong tendency to make him into a heroic figure who testified to the uniqueness of this one God and, therefore, to the falseness of idolatry.

And he's nearly martyred for it. He's presented as a rediscoverer of monotheism, as he is—no coincidence—also in Islam, which is very much influenced by these older Jewish traditions. I think the key point in those traditions about Abraham as a so-called monotheist is this rejection of materialism or materialist determinism, including a rejection of astrology, the notion that there are mathematical formulae that govern the movements of the stars, the astral bodies that then also govern human history, that also govern what happens on Earth.

Instead, there's an affirmation of providence, of a personal God who is the master, ultimately—you have to put a lot of emphasis on the word “ultimately”—of human destiny and the way things turn out. In other words, a providential God governs history—a personal, providential God governs history. And his will ultimately triumphs. That's what these texts are largely trying to say.

The Jewish philosopher, Philo, early in the first half of the first century CE, writing in Greek, says that Abraham had an epiphany when he realized that there's a charioteer and a pilot—meaning someone who captains a ship, who controls the helm of a ship—of the universe, and that the astral bodies are not ultimate. They can be understood by what we might call astronomy. But the predictive value of what we would call astrology is overridden by divine providence.

If you try to apply that today, you might say it's a rejection of social, cultural, or genetic factors as absolute, as though what you think and the way you act and what your morality is and what your destiny is are completely determined by your genes or your material situation, your social class, whatever—race. No, there's a notion of free will for human beings and of a free will of God that interacts with human beings so as to make actual human history. So I think that notion of the uniqueness of God and of the people Israel's exclusive loyalty to him and his ability to override what you might call the natural processes according to his providential will, that is really what I think is central to the Jewish appropriation of Abraham.

In Inheriting Abraham, you point out that in Genesis, Abraham doesn't actually engage in any of the Jewish tradition’s practices, except circumcision. So can we say he was the father of the Jewish people?

Underlying your question is an assumption that the Jews, the Jewish people, the people of Israel are, a church or a confession, a religious body. And if he isn't—I won't say believing—but practicing the religion, then how could he possibly be their father? To which my answer, Paul, is consider that word “father.”

Father is, by nature, biological. Judaism accepts converts. Rabbinic Judaism has always accepted converts, but it's not a missionary religion. And it doesn't assume that you have to be born again, so to speak. But if you are Jewish by birth—so he's certainly the father of the Jewish people, whether or not the texts present him as practicing the full 613 Commandments that the Talmudic rabbis say are in the Torah, in the Pentateuch, the five books of Moses.

I think, clearly, Genesis does not present him as practicing those. He's still the father because we're not dealing with a church, where the question of belief and practice is the key thing about the founder. He is a father.

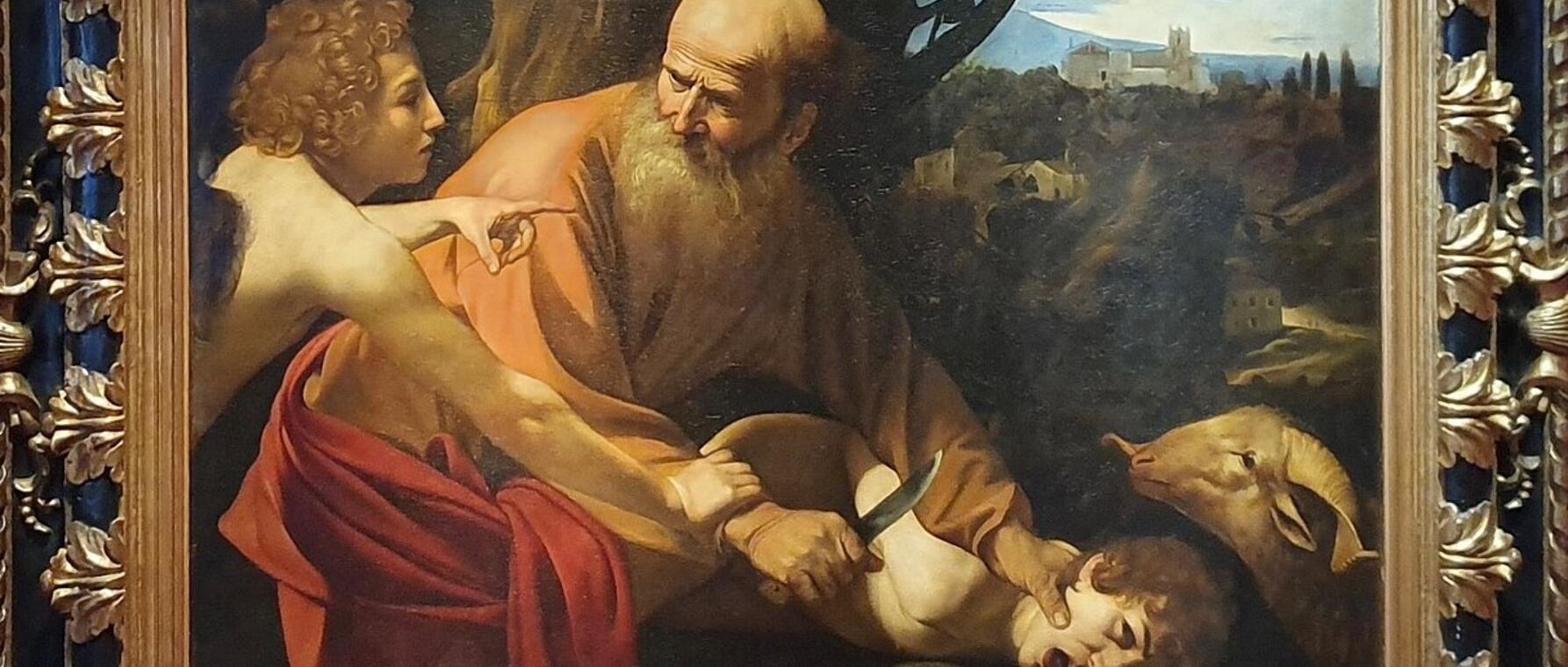

In the book, you also deal extensively with the binding of Isaac. In fact, I think it may be the longest chapter. It's a jarring story. Can you say a bit about how it's commonly misunderstood, both by those who point to it as evidence of religion's irrationality and barbarism and by those who see it as an exemplar of faith and devotion?

I think the point has to do with Abraham's learning to act sacrificially. If I were to say to you, Paul, you know what? You get up and go. Leave home. Break with your father's household. And I'll give you your own country, and I'll make you rich and famous and make you the ancestor of a famous nation.

And you'll be a byword of blessing. People will bless themselves by saying, I really would like to be like Paul Massari. Or I bless my children and say, may you grow up to be like Paul Massari, which I'm sure people already do. But imagine you were offered a country if you did that.

I don't know about you. I'd do it. I'd do it. I'd say, it sounds fantastic. So Abraham's obedience up to this point has paid off, to put it crudely. He's been trained to do the right thing. But the question is, what, if instead of breaking with his father and so forth, what if he has to leave home with his son whom he loves? [HEBREW] Your only son, your favored son, son, whatever, Ishmael, having in the narrative line in Genesis 22 been expelled or whatever, or at least gotten off the scene. It's more complicated than that, but that being the case—and then offer him up as a sacrifice.

The issue is not murder. The issue is sacrifice. The language is not secular killing in Genesis 22. It is sacrificial. That's why there's an altar. He's to be offered up as a sacrifice to this God. Now you're not just looking out for number one and maximizing self-interest. Now what you have to do is to part with something and something dear to you.

Is Abraham going to do it in that case? In other words, does he believe the promise of the great nation will descend from Isaac? Because Isaac is not married and has no children at that point. As you know, infertility is hereditary. If your parents didn't have any children, you won't either. If Isaac has no children, Abraham will have no grandchildren through Isaac. We can be pretty sure of that. And so Isaac dies childless.

And yet, according to Kirkegaard, Abraham's faith in the promise is so great, he acts obediently to God, knowing that, in fact, in the end, he will somehow get Isaac back, which is what happens. The sacrifice is called off, and Abraham is commended not for willingness to do a child sacrifice, but for his obedience—for the fact he did not withhold his son. He is willing to act sacrificially.

I think it is a mistake to say, well, that shows you're just supposed to act mindlessly—whatever God tells you, however immoral or unethical, you're supposed to do it. It's about Abraham and the promise to Abraham and about Isaac and what Isaac represents, in terms of that promise. That's radically different from what Everyman is supposed to do.

It's not some sort of ethical paradigm. If you hear a voice in your head telling you to go murder your son, then you have to do it. That's a very simplistic, childish way to read this story, though I have to say, a very large number of people, including some accomplished scholars, do read it in that unsophisticated, childish way, in my opinion.

What role does the story of the binding play in Christianity? Do you see it as prefiguring the story of the passion of Christ?

I think to some extent, “this is my beloved son” and so forth, “with whom I am well pleased”—that is designating Jesus as a kind of Isaac figure. And the fact this is taking place at Passover time. According to the synoptic Gospels, I think Passover comes on that Thursday night. According to the Gospel of John, it comes on the Friday night. They seemed to be working with different calendrical systems or imagining a different year between Matthew, Mark, and Luke, on the one hand, and John, on the other.

But already in Jubilees, which I just mentioned, long before this, 200 years before this, there already was a Jewish tradition that sees in the Aqeda, the binding of Isaac, the etiology, the foundational story for Passover, pre-exodus, with the first paschal lamb would have been Isaac. It may have been the ram that takes the place of Isaac at the end of Genesis 22, but it would have been Isaac.

So if Isaac is identified with the lamb and the ram, Jesus is strongly identified with the lamb or the ram in the New Testament. So I think there's a sense in which the large parts of the New Testament story of Jesus are Midrashic adaptations and echoes and appropriations of Genesis 22. I think that's extremely important for understanding the genesis of Christianity and their understanding of this binding of Isaac.

You cite Saint Paul, who writes in Romans that Abraham is “the father of all who believe but have not been circumcised, in order that righteousness might be credited to them.” How is this emphasis on faith a departure from the Jewish tradition of which Paul and Jesus, after all, had been a part?

Well, the emphasis on faith is very important in Judaism and continues throughout the Jewish tradition. The interpretation of Abraham as a person of faith, a believer—is very, very important. It wasn't discovered by [the Danish philosopher] Kierkegaard or whomever. But Paul does something more than that.

For Paul, that verse that you quoted is rephrasing or echoing, maybe even citing to some extent, Genesis 15:6, which says something like, he—referring to Abraham, Abram—had faith or trusted in the Lord, and he accounted it to him as righteousness—understanding the "he" as the Lord, not Abraham. The subject of that second clause is not specified. It's just some masculine singular person. In other words, he, meaning Abraham, had faith in the Lord, and [the Lord]credited his righteousness.

As Paul understands it, that means Abraham's righteousness depends on his act of faith, which is in Genesis 15, which the mathematicians among your listeners will know comes before Genesis 17. And therefore, you could be righteous apart from circumcision, which is in Genesis 17, because he's already declared righteous on the basis of his faith in Genesis 15, verse 6. That's the key point.

So Paul establishes here the idea that a Gentile, a non-Jew, could achieve the status of the people of Israel and inherit the Abrahamic promise without the Torah and its Commandments, even without the one commandment that Abraham clearly has, which is “brit milah,” the circumcision, the sign of the Covenant through circumcision that we see in Genesis 17. So that is the departure.

You also write that Islam actually focuses more on Abraham than either Christianity or Judaism. So how does the Quran conceive of Abraham? And how does it differ from Judaism and Christianity, particularly on the question of descent?

The Quran presents its message as the restoration of the religion of Abraham. That's really not a new thing. It's a restoration of a primordial religion, maybe the primordial, natural human religion of Adam—but certainly where Abraham is a major figure in that chain of prophets that I mentioned that culminates in the seal of the prophets, namely Muhammad. So there, Abraham is not a father.

The biological idea that you have in Genesis or the metaphorical fatherhood idea that you have in Paul and elsewhere in Christianity, that's really not the image. The image is more of a prophet and, therefore, a foreshadowing or antecedent of Muhammad. And in fact, if you consider Muhammad's conflict with his townsmen, his having to leave Mecca for Medina, the whole question of idolatry—all that's heavily influenced by those traditions about Abraham as the iconoclast, Abraham as the person who sees through idolatry, sees through iconography, and so forth, that you have in Second Temple and rabbinic Judaism.

So in that sense, it's a different image. And therefore, when you have something like the Aqeda, the binding of Isaac in the 37th sura of the Quran, you have a short version of the story. But it never names the son. Again, it's not a line of descent that's being traced. It's not a covenant that's being traced the way it is in different ways in both Judaism and Christianity.

That's where Islam, in that sense, stands apart to some degree from Jews and Christianity. Just as on that Trinity issue, Judaism and Islam stand together against Christianity. These all have certain things they have in common and certain things they don't have in common.

Finally, some working for peace in Gaza now are again invoking the idea of the Abrahamic faiths as a way to promote interreligious dialogue. Where would you suggest they look instead if, as you write, "It is surely the case that Jews, Christians, and Muslims have more in common than most of their adherents realize"?

I'm an advocate of inter-religious dialogue if it's honest and respectful and civil. It's unrealistic to think that fanatics of whatever sort, but especially those who are, let's say, committed to wiping out a whole country and are open to the use of terrorism—that they'll be attracted to inter-religious dialogue.

A colleague I had when I used to teach at the University of Chicago Divinity School, Martin Marty, had a line I think I'm quoting correctly. "The committed are the least tolerant, and the tolerant are least committed." It's easy to be tolerant if you don't have a commitment. If you're a relativist or you really don't care—you think all this theology stuff is a lot of nonsense—well, it's very easy to be tolerant. And if you're committed, it's hard to be tolerant.

That's the hard thing—to get people who are profoundly committed to their own religious tradition to be open to notes in their own religious tradition that are maybe more developed in another religious tradition. That's hard to do. So I think realistically, I don't think inter-religious dialogue will solve an immediate crisis, like what's going on in Gaza.

I think that in the larger culture, it's important for people to understand, to study these different religions—study their common scriptures, study their different interpretations, applications of those scriptures—their different canons of scripture are very important—and be very careful about absolutizing their own religion. The easy thing to do is to say, you say “ee-ther,” I say “eye-ther.” You say “potayto,” I say “potahto.” It's all just the same thing.

No, it's not all the same thing. I've had students over the years say, well, isn't it true all religions teach the same thing? And my answer is one word: no. They have things in common, things not in common. To recognize genuine religious diversity is something that's very, very hard.

So I think that establishing a framework where one understands the common appropriation of a figure like Abraham can, in the long term, have positive effects on peace in the world. But when you deal with hardcore fanatics or people who absolutize their own religion and never wonder how the other side actually sees it in their own voice, they're not going to be attracted to or influenced by inter-religious conversation.

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast