Breaking the Wave

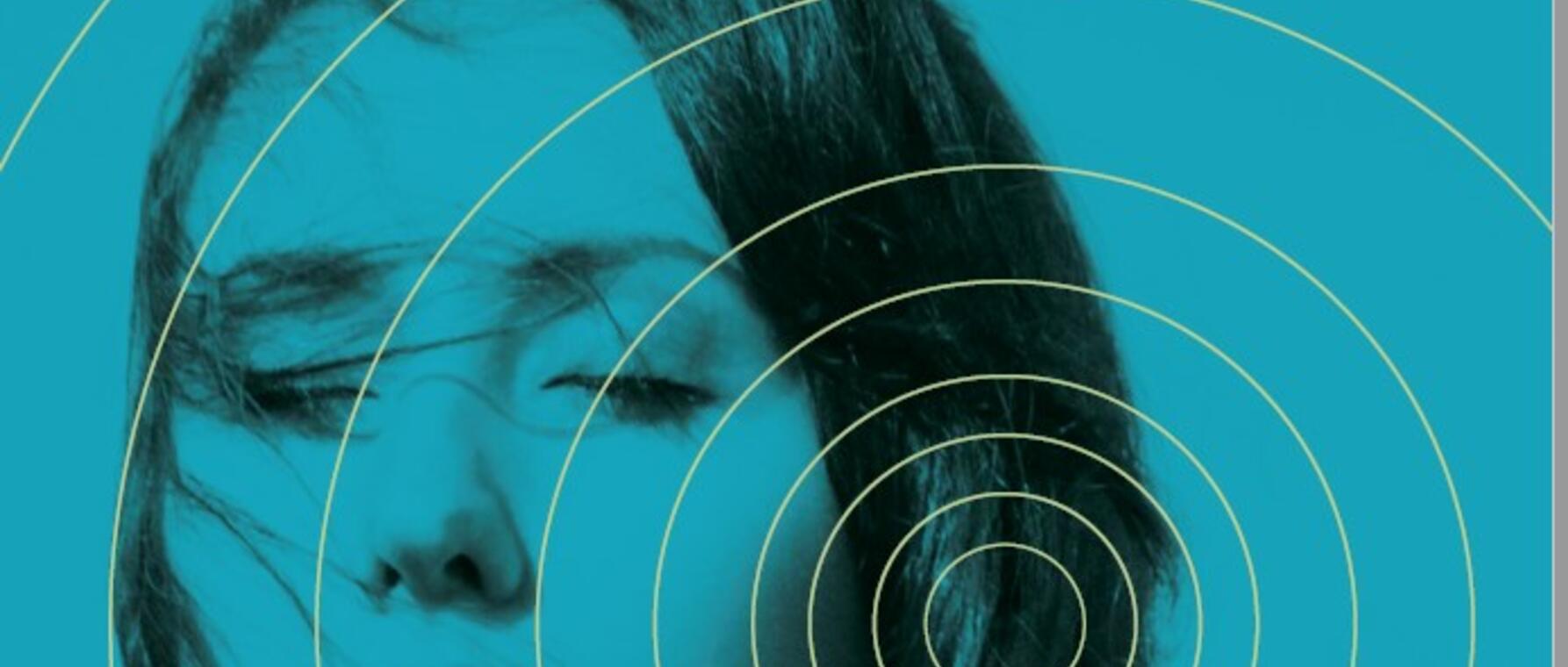

Sasha Siem transcends the boundaries between music, spirituality, and healing

It is 2019—before the pandemic, before the war—and Sasha Siem stands tall and strong on the rooftop of a building in Jerusalem. It is the nexus of three of the world’s great religious traditions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—a place of great wisdom and community; a place of great contention and suffering. Bathed in the city’s warm sunlight, she sings to a world in conflict with itself:

We are holey, we are wholey, we are holy,

There are holes in the day and in the dark.

“Physically and geographically, Jerusalem embodies a split and also the potential for holiness—in the sense of deep respect for all of humanity,” Siem says. “That’s why we chose to shoot the video for the title track of my album wHOLeY there. It felt like a prayer in a way; like putting a beam of energy into the heart of a city that has, of course, represented so much for so long.”

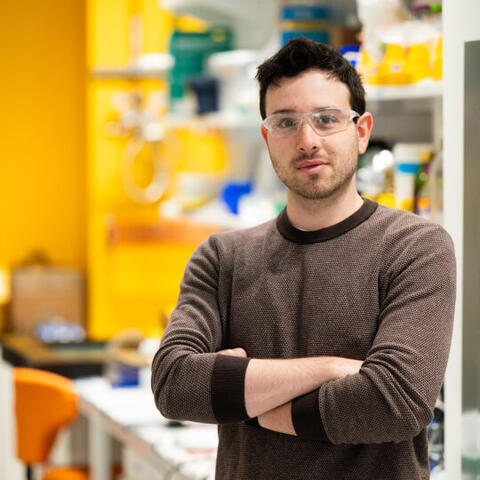

An award-winning composer who has worked with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Opera House, and the London Philharmonic, Siem, PhD ’11, now focuses her talents on writing and performing songs that engage the spirit and foster healing at a time of fragmentation and strife. In many ways, she’s been on this path her whole life. But the journey took a crucial turn during her time at the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS).

Finding Her Voice

The daughter of a Christian father of Norwegian origin with possible connection to the indigenous Sami people of the north, and a mother descended originally from Eastern European Jews but born in South Africa and raised in Britain, Siem began training as a classical pianist and cellist when she was only 5 years old. When she was 11, Siem’s mother gave her a book of Maya Angelou’s collected poems. Siem closed the door to her room—a “sacred space” where a sensitive pre-teen challenged by dyslexia could retreat from a world that often felt overwhelming—and started flipping through the book. She paused at one poem in particular—“I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.” It spoke to her. She spoke back.

“I just started singing the lines of the poem as I played the piano,” she says. “There was something almost mystical about it. I was swept up by the theme of freedom, which has since run through my work and my life.”

The prospect of raising her voice in public terrified Siem, who had adopted shyness as a self-protective mechanism. She focused on composition and study, obtaining her undergraduate musicology degree from the University of Cambridge. “Through the lens of music, I explored the physics, history, and philosophy of sound,” she says. “It was a holistic approach. I was excited to keep going, so I came to Harvard Griffin GSAS to study for my PhD.”

Siem had loved her deep dive into musicology and enjoyed the composing she had done, but the intellectualism of her work increasingly weighed on her. She longed for the innocent, soulful creativity that inspired her to bring poetry and music together as a child. Harvard turned out to be the perfect place to bring her life back into balance. She continued her studies of musicology, traveling to Milan, Italy, to examine illuminated manuscripts of the ancient Ambrosian hymnody of the Roman Catholic Church and publishing a paper on their meaning. But she also ventured to Harvard’s Department of English to study with some of the country’s leading poets. “Studying poetry with [Boylston Professor of Oratory and Rhetoric] Jorie Graham at Harvard was the first time I started to think of myself as a poet and take the lyrical side of my work more seriously,” she says. “I was so fortunate to be accepted into her course. It was an enlivening and life-changing experience for me.”

Siem also explored the University’s Department of Visual and Environmental Studies, taking a course in poetry writing from a visual arts perspective taught by Damon Krukowski, AM ’88, poet, publisher, and drummer for the legendary Boston dream pop band Galaxie 500.

“Sasha was unusual in her willingness to experiment outside her expertise, despite being well on her way at the time toward her graduate degree,” Krukowski says. She outdid even college freshmen in her openness to new ideas, new sounds, and new techniques. And yet she already had the skills to apply those to professional work—a valuable skill of its own!”

While Siem was exploring poetry and art at Harvard, she also met the late British composer Jonathan Harvey, whose works Passion and Resurrection and Weltethos often explored religious and theological themes. Reviewing one of Siem’s compositions, Harvey saw a kindred spirit.

Siem remembers Harvey telling her, “You know there’s something really unusual here. Most pieces are built of harmony and melody as distinct components. But with your work it’s as though there is no distinction—all elements are unified in one embellished line.”

“He saw almost a philosophical idealism in my music,” Siem says. “And he was right. I have a motivating desire for wholeness.” By the time she received her PhD in 2011, Siem had recorded and released a six-song version of her debut album Most of the Boys. The pursuit of wholeness—and a kind of holiness—had become central to her work and life.

By encouraging our creativity and ability to channel inspiration, music can help us transcend our smallness and unite us with what’s beyond. It can ignite hope as well.

—Sasha Siem

How the Light Gets In

After graduation, Siem continued to compose, fulfilling commissions for the Royal Opera House, the Rambert Dance Company, and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. In 2008, she also took part in the Panufnik Scheme, a program run by the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) for young composers at the outset of their careers. “Sasha wrote for the full orchestra under the mentorship of a distinguished group of composers and individual members,” says Kathryn McDowell, managing director of the LSO. “Her work impressed the orchestra with its color and flair. As a result, her composition Ojos del Cielo was recorded for release on our LSO Live label.”

For her work, Siem received both a British Composer Award and the Royal Philharmonic Society Composition Prize. She was delighted by her success, marveling at what she described as the “spectacular nineteenth-century voices” singing the music she wrote for the Royal Opera House. Still, she wanted to convey a more contemporary sentiment, one best expressed, she said, through her own “fragile, vulnerable, less than perfect voice.” She decided to embrace singing and songwriting.

In 2015, Siem released her first full-length album—an augmented version of Most of the Boys, produced in Iceland by Valgeir Sigurðsson, whose previous collaborations included Björk’s Oscar-nominated score for director Lars Von Trier’s film Dancer in the Dark and Feist’s 2011 album Metal. Calling it “a brazen take on womanhood that’s also pleasing to the ear,” Boston Globe music critic Maura Johnston described Siem’s record as a dive into “the dichotomies that women have to navigate, sometimes begrudgingly, in twenty-first-century society; personal and public selves, acting mannerly and offering honesty, showing confidence while nursing wounds.”

Helping to heal humanity’s wounds has increasingly become an aspiration of Siem’s in recent years. It was the driving force behind her 2020 album wHOLeY—and the Jerusalem-based video for the album’s title track. “I wanted to play with the idea of wholeness,” she says. “Leonard Cohen wrote ‘There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.’ Equally, there is a recoverable wholeness once we’ve been through a healing process, and a holiness—a divinity—at the core of our existence, which is unbreakable no matter what we’ve been through. In the album, I wanted to explore the relationship of those three phrases, to present them almost as a pathway that all of us can travel if we wish to.”

wHOLeY is built around the “miracle tone” of 432 Hz, an alternative tuning standard for music purported to be more natural or spiritually resonant than the standard 440 Hz. “We live with quite an artificial tuning system in the West that developed with Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier,” Siem explains. “The equal partition of tones is, in a sense, actually out of tune when you compare it to the different proportions you find in the natural world. There’s a lot of controversy about whether the miracle tone is real or not but in my lived experience—and I did some informal testing—it has a profound healing effect on the body and the mind.”

Healing and Hope

Beginning this year, Siem hopes to bring the healing power of sound to new audiences by merging her creative work with her vocation as a teacher. She recently launched five new online courses accessible through her website www.sashasiem.com. (She hopes to teach the courses in person as well at various times and locations.) The classes include From Harm to Harmony, which teaches participants to use songwriting or the creation of vocal sound to work through trauma; The Music of Motherhood, which facilitates mother-child bonding through song; and The Sacred Power of Songwriting, an anthropological and historical journey through sound that considers practical ways to bring its healing force into everyday life.

Siem also creates bespoke “sound ceremonies.” In the video for her song “Eve Eyed (Women’s Circle),” for instance, women in white robes gather in a candlelit sacred space where they sing, lay hands on one another, and rest with each other. “It’s a celebration of womanhood, of sisterhood,” Siem says. “We wanted a place they could enter with reverence, appreciating the spark of life in one another, leaving the everyday hustle and bustle outside. All the ladies were on a high for at least a week after they left, able to bring that same nourishment and gratitude to all our other interactions.”

There is a recoverable wholeness once we’ve been through a healing process, and a holiness—a divinity—at the core of our existence, which is unbreakable no matter what we’ve been through.

—Sasha Siem.

Inspired by her experience at Harvard Griffin GSAS, Siem continues to develop as a literary artist as well. Working with poet Kim Noriega, a finalist for the Joy Harjo and Edna St. Vincent Millay poetry prizes, Siem developed and completed her first collection of poems, The Way of Light on Water (as yet unpublished). “It’s a slim and stunning volume that explores the complexities of motherhood from the devastation of miscarriage through the beautiful mess that is parenting a small child,” Noriega says. “Sasha’s musicality is immediately evident in her poetry. Her use of imagery, especially auditory imagery, often imbues her work with a distinctive magical realism that I find compelling.”

Siem looks forward to the release in 2024 of True, her fourth album in the last five years. Stripped back and spare, the songs bring her back to her roots of piano and voice. All address the nature of the stories around which we build our lives, where they begin and where they end. “Stories are crucial, but they can keep us contracted,” she says. “It’s being able to see them as stories that enable us to step across divides.”

Through songwriting, teaching, and ceremony, Siem hopes to empower those who don’t think of themselves as musicians to create their own songs as a practical way to unlock—and heal— the parts of their lives that often cannot be put into words.

“With music, our physical boundaries can dissolve,” she says. “It can be a portal into different perspectives on our life. By encouraging our creativity and ability to channel inspiration, music can help us transcend our smallness and unite us with what’s beyond. It can ignite hope as well. As a musician, a mystic, and a mother, I want my life’s work to ignite that healing and hope.”

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast