All Animals Are Equal

The breakdown of the species divide in Soviet cinema

Research at Risk: Since World War II, universities have worked with the federal government to create an innovation ecosystem that has yielded life-changing progress. Now much of that work may be halted as funding is withdrawn. Find out more about the threats to medical, engineering, and scientific research, as well as how Harvard is fighting to preserve this work—and the University's core values.

At the end of the 1957 western, Old Yeller, a teenage boy reluctantly puts down his beloved dog, which has contracted rabies after fighting off an attacking wolf. The scene is one of the most famously heart-wrenching moments in American cinema—and precisely the type of trope that drew recent GSAS graduate Raymond De Luca to study the portrayal of animals in film.

“I was always confused by feeling ‘worse’ for animals when watching movies as a child growing up, because we are told, constantly, that humans are superior to animals and, therefore, deserve greater moral consideration,” De Luca says. “My research interrogates that feeling as well as misplaced notions of human exceptionalism.”

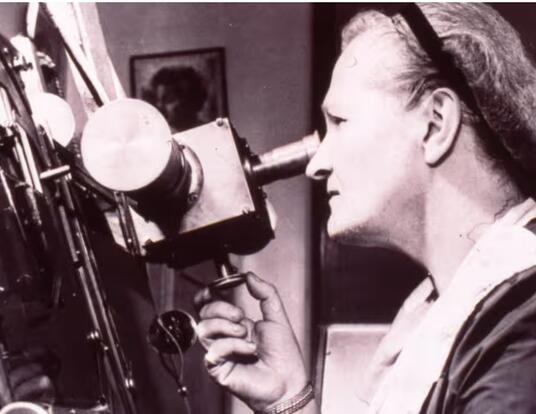

As a young film scholar, De Luca casts his gaze not on Hollywood but the old Soviet Union, exploring the ways that filmmakers portrayed animals while building a communist culture—and probing the animal-human divide. In so doing, he offers insight into how humans perceive distinctions between themselves and animals—and how those perceptions can be challenged.

Blurred Lines

De Luca says claims that humans were a superior species were really codified during the French Enlightenment. The philosopher René Descartes, for instance, conceived of animals as things with no interior dimension, only reactive bodies, machinelike. The work of Soviet filmmakers challenged the enlightenment view, equalizing humans and animals, sometimes promoting and sometimes demoting both. De Luca points to the Soviet revolutionary era, when the boundaries between humans and animals were blurred, often to encourage totalitarian rule.

“This notion existed that humans and animals could participate in the building of Soviet communism together, that they could be engineered in the same way to do the same thing,” he says. “That close association provides the ideological license for the state to start treating humans like animals, and people become disposable and utilizable in the same way.”

Soviet filmmakers anthropomorphized animals through the 1930s and 1940s, De Luca says. Director Grigori Aleksandrov’s 1934 musical comedy, Jolly Fellows, for instance, depicted animals as talking and childlike. “The spectacle of talking animals aspired to infantilize viewers by inducing a state of impressionability that paved the way for propaganda.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, the end of Stalinism and a rise in pet ownership among Soviet citizens influenced the ways that filmmakers depicted animals. De Luca says that in this era, films such as Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev used animals to explore the recovery of dignity in the wake of brutality and repression. These works also explored death in a manner that forced viewers to consider their own positions on the treatment of animals—and people. “Filmmaker Aleksander Sokurov, who was inspired by Andrei Rublev, made a film called Days of Eclipse that focused on how late Soviet life reduced the vitality of both humans and animals,” De Luca says. “These years were called ‘the era of stagnation’ for the torpor and lethargy of everyday life.”

This notion existed that humans and animals could participate in the building of Soviet communism together, that they could be engineered in the same way to do the same thing.

–Raymond De Luca

As Stalinism unwound, De Luca says, filmmakers like Kira Muratova depicted intermixing and hybridity between animals and humans in ways that promoted the dignity of both. “This was the ribbon tying my research together—how we get from this equal demotion of humans and animals to a promotion of all forms of life.”

To Lift up All Species

By 1989, as the USSR approached dissolution, De Luca says that films like Muratova’s Asthenic Syndrome were “obliterating the lines between humans and animals, advocating for new forms of interspecies community.” He describes one scene where the characters contort their faces into grotesque and animal-like expressions and make animal noises. This deconstruction of two key human features—facial expression and speech—complicates the boundary between human and animal.

“At this point, animals are looked at as a source for hybridity,” De Luca says. “Humans and animals are intermixing. They are being equalized again, but this time it’s not to dehumanize or demote either; it’s to uplift both.”

Professor of Slavic Languages and Literature Stephanie Sandler, De Luca’s faculty advisor, says that his research “asks why some key Soviet films move wildly between images of animal life as filled with vitality, and those of indifference, brutality, and even cruelty.”

“For Raymond, this vacillation defines the films’ ambivalent view of human life, animal life, and human ethics,” Sandler says. “The wider implications of this work reframe our relationships to animals, asking whether genuine ethics can ever be constituted so long as animals are regarded as subordinate to humans.”

Beginning this academic year, De Luca will join the faculty at the University of Kentucky, where he will teach classes in Russian language and cinema. He also has plans to turn his research on Soviet Cinema into a book.

“It’s exciting, and I feel like I’m off to a really strong launch for the career,” he says. “I count my lucky stars that the first time I hit the job market, it worked out. This provides me the platform to continue and deepen my research.”

The wider implications of [De Luca’s research] reframe our relationships to animals, asking whether genuine ethics can ever be constituted so long as animals are regarded as subordinate to humans.

–Professor Stephanie Sandler

De Luca says he hopes that, by looking at animals through the lens of film, his research can enable viewers to appreciate them not just as characters or images on a screen, but as living creatures—ones that were often intentionally manipulated and coerced.

“Film lets us encounter animals in their singularity as historically-locatable, material beings before a camera,” he says. “I'm less interested in animals-as-metaphors or as-symbols than as living creatures whose presence on screen raises questions about ethics, autonomy, treatment, and there-ness.”

Photos: Creative Commons, Banner: The Kobal Collection/Kobal

Get the Latest Updates

Join Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Colloquy Podcast

Simplecast